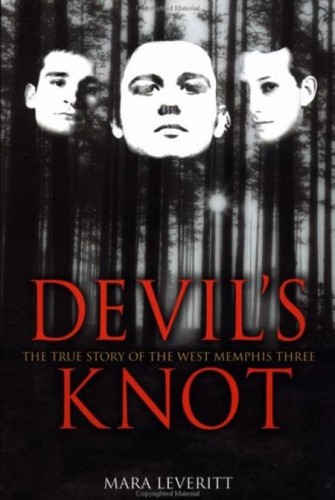

During the month of October while I drowned myself in slasher flicks, I chose four books that dealt with evil, horror, etc. to read alongside the horror. Mara Leveritt’s true crime book, Devil’s Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three, was one of the selections (and is currently being made into a major motion picture). The book tells the unfolding tale of three teenagers who were accused, tried and convicted of killing and mutilating the bodies of three 8-year-old boys in the small town of West Memphis, Arkansas. The way the book plays out is much like that of The Crucible by Arthur Miller or any other fiction (and non-fiction) accounts of the Salem witch trials.

During the month of October while I drowned myself in slasher flicks, I chose four books that dealt with evil, horror, etc. to read alongside the horror. Mara Leveritt’s true crime book, Devil’s Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three, was one of the selections (and is currently being made into a major motion picture). The book tells the unfolding tale of three teenagers who were accused, tried and convicted of killing and mutilating the bodies of three 8-year-old boys in the small town of West Memphis, Arkansas. The way the book plays out is much like that of The Crucible by Arthur Miller or any other fiction (and non-fiction) accounts of the Salem witch trials.

The police and prosecutors kept trying to make the killings into the work of the Satanic cult led by Damien Echols and his accomplice, Jason Baldwin. Any evidence they had for satanism as a motive was circumstantial, at best, and most of it was pointed at Damien Echols alone. The prosecution’s main expert on the occult received his degree from a correspondence school and undertook no formal study on the subject but was merely self-taught, a fact unknown to even the prosecutors until it came out in the trial. All of the other evidence that the police had on these three boys was merely circumstantial as well. They made their case solely on the accumulation of the circumstantial evidence alone. Jesse Misskelley, Jr. was convicted of one count of first degree murder and two counts of second degree murder, and Damien Echols and Jason Baldwin were convicted of three counts of murder. Echols was sentenced to death and Baldwin was sentenced to life in prison without parole. Appeals would take place soon after.

It is hard to read such a story and still have faith in the American justice system. A sense of outrage lurks within the story in Mara Leveritt’s book. It was a miscarriage of justice, plain and simple. It didn’t help that the local Christian church was a loud voice feeding the occult frenzy behind the weak case of the prosecutors instead of fighting for the three defendants, who by this point were victims themselves. But the final pages of this bizarre and frightening tale reveal something strikingly reminiscent of the “deeper magic before the dawn of time” (C.S. Lewis). At this point, I hand it over to the brute force of Jason Baldwin’s words, as reported by Mara Leveritt:

As the ninth anniversary of the murders approached, Jason was living a life as close to a middle-class life as he could imagine inside a prison. Because he was quick to learn computers and maintained an impeccable prison record, he’d been assigned to a series of white-collar jobs in various clerical positions. He’d joined the prison Jaycees and begun to study investments. “I don’t want to get out and be that sixteen-year-old kid I once was,” he said. “I want to keep up.”

He’d taken college courses in subjects like anthropology, accounting, and American politics–“because I want to see what our government’s built on”–and dreamed of attending law school. And he had a sweet-heart. The correspondence that he’d begun in 1997 with young Sara Cadwallader had grown into a serious romance. She was in high school when they’d met. Now Sara had graduated from college and had herself been accepted into law school. Jason credited Sara, his faith in God, and the support of friends, many of them “total strangers,” for his emotional stability–for his ongoing belief “that right will prevail.”

“I have grown up in prison,” he wrote at the end of 2001. “Even with all that I have suffered, I have not allowed myself to become hateful, spiteful or resentful of either those who put me here unjustly, or of those who allowed it to happen. I know you’ve got to love life, enjoy it, embrace it while you’ve got it. I love this country we have. I love America and her people. And I hope that someday I will be able to live here as a free man again, with my reputation intact.”

Jesse, Damien, and Jason all had different visions of that life would be like if they were freed. Jessie dreamed of a “big party.” Damien said he wanted to “disappear” with his wife. Jason foresaw a life of activism relating somehow to law.

“Being in here has made me stronger,” he said.“It’s made me more reflective on things I should be proud of and enjoy, things like freedom. I don’t take things for granted. And I’m not as naive as I was. The reason I’m here–the real reason–is that someone had to pay the price.” Jason said that the police and prosecutors had been “content just to say we did it” and that that had been “enough” for the public. But he added that he understood the public reaction. “I used to think that way too,” he said. “To me, a suspect meant, ‘That’s who done it.’ But I didn’t do it, and that’s the main matter.

Indeed, someone always has to pay the price to satisfy the demands of the Law and justice. Baldwin recognizes that often the innocent are the ones who pay the price, as the accusers are themselves guilty (John 8). The feeding frenzy for justice must be satisfied, we must have a scapegoat. This story offers a glimpse into God’s love as it was incarnated in the death and resurrection of Christ, who willingly accepted the false conviction by divine and human Law. But Law is trumped by grace, and justice lingers into love (C. Wesley). Praise God.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply