The End Is the Beginning

We are all familiar with fictions in which the desire for consolation puts the beginning and middle “under the shadow of the end.” In fact, we all write numerous such fictions, many of them daily: think of every argument that takes place in your mind, how the end is determined, and the way that the plot elements are arranged reflexively to lead concordantly, plausibly, to that end.

Among the more unjust, unfair, and tragic end-determined fictions that come to my mind is the Misjudgment of Tony Romo. The fiction about Dallas Cowboys’ quarterback Tony Romo is weighed down to an unfair degree by a couple plot turns—his fumbling of a snap at the end of the 2007 wild-card playoff game against the Seattle Seahawks and his romance with Jessica Simpson (a mistake, to be sure, but one that occurred off the field)—which are entirely irrelevant to his performance as a quarterback.

This fiction omits the fact that, in the 2007 playoff game, Romo marched his team down the field for a chance at said game-winning field goal, and the story ignores several of Romo’s transcendent performances—the overtime victory to which he led the Cowboys against the San Francisco 49ers this past season, while ailed with a broken rib and punctured lung; the frequent Favresque improvisations which force all jaws to the ground, most notably in 2007 when the Cowboys center snapped the ball over Romo’s head twenty-five yards downfield, after which Romo darted backward, picked the ball up, and slalomed thirty yards through a blizzard of defenders like moving buoys for a first down; and, yes, a few fine performances in high-stakes games, including consecutive regular-season and playoff contests against the Philadelphia Eagles in the 2009 season in which the Cowboys outscored those baleful birds by the combined score of 58-14.

The point is not that the Misjudgment of Tony Romo is wholly devoid of factual support. Most fictions are supported by some facts. I, for one, watched in a sports bar in suburban Detroit last fall as Romo single-handedly won the game for the opposing team with three Pee Wee league throws in which the football landed in the hands of Detroit Lions defenders. I tore my Cowboys jersey off as a left the bar, to a hail of jeers from a normally genial group of fans. I swore I would stop publicly defending Romo’s reputation (and yet here I am).

No, the point is that a fiction faithful to the record of reality would encompass all of the relevant data points (both Romo’s extreme on-field wizardy and his capacity for shocking acts of quarterbacking irresponsibility) and ignore the irrelevant data points (such as the inexcusable decision to date Simpson). The Misjudgment of Tony Romo is a fiction, an object of the human mind, just as would be the Generous Judgment of Tony Romo, or the Accurate Judgment of Tony Romo. The Accurate Judgment of Tony Romo would be no less a fiction of the human mind for its accuracy, for its correspondence with the fiction of reality. All three fictions feel pretty similar in their correctness to the storytellers.

“What can be thought must certainly be a fiction,” Nietzsche wrote in the fragments that became The Will to Power. And as a fiction that can be thought, a story with supporting data points, it will be configured by the storytellers who begin with an ending in mind, and the supporting data points can be strung together like yellow and red beads on a necklace, leaving out the silver and blue beads. Thus, the Misjudgment of Tony Romo might begin with any ulterior ending, such as the bad wishes of those who have it out for the poor Dallas Cowboys or the jealousies of Redskins fans, or Romo might be a scapegoat for observers harboring a well-founded distaste of Jerry Jones. The point is that the plot of the story derives its shape from a predetermined ending, and that behind every visible twist and turn of the plot is a single plotting mechanism, a mechanism which, while invisible, gives the fiction its shape. It’s always the least convenient data point that we forget, isn’t it? Perhaps it’s nothing more than the ease of forgetting it that makes that data point inconvenient. Poor Tony.

The Grim Shadow of Self-Knowledge

Poor Tony, indeed. The tragic element in Barnes’ The Sense of an Ending is supplied by Tony Webster’s decision—one that appears on its face honorable—to seek out the occurrences that formed the basis of reality’s fiction. Tony in the Future has discovered those occurrences, and looks backward. Tony in the Present drives toward reality’s fiction and, like a jungle explorer cutting a pathway through a dense forest, is tangled in the brush of his own mental fictions.

As we travel with both Tonys, and observe both reality’s fiction and Tony’s mental fictions, we see that Barnes himself has learned that Kermode’s central insight—that literary fictions demonstrate over time interplay between the culture’s conception of the temporal destination of human affairs and the shape of fictive plots—simply reflects the fiction-making behavior of individuals. For individuals—unextraordinary individuals like Tony Webster—create mental fictions beginning with an imagined conception of the temporal destination of human affairs. In this fiction-making, reality’s fiction, the realm of actual occurrences, individuals borrow the beads in the same spirit of convenience as Tony Romo’s critics. And on this point Barnes’ novella obtains is penetrating element: his understanding of the particular method of human self-consolation, the single plot device at the foundation of every individual’s mental fiction.

It doesn’t give away too much to state that something Tony did during his days with Veronica and Adrian stands in the gap between Adrian’s death and Veronica’s mother’s bequest. Tony aims to discover what that thing is, against the advice of his ex-wife, who warns him about what painful facts he might find out about himself. As Tony in the Present uncovers each new fact about Adrian, Veronica, and her mother, Tony in the Present reformulates the fiction of his life, and its relation to theirs, as necessary. Each new fact disconfirms the old fiction, but the old fiction is not discredited. Rather, the basic fiction, Tony’s default fiction, is strictly adhered to. Each new fact is bent to fit that single, central plot device, as much as a climbing plant wraps around a garden trellis.

For example, Tony’s first fiction: What is the purpose of the bequest? Tony obtains Veronica’s email address and asks her. Her response, as I mentioned: “Blood money?” Tony’s interpretation is instructive.

I looked at the words and couldn’t make sense of them. She’d erased my message and its heading, not signed her reply, and just answered with a phrase. I had to call up my sent email and read it through again to work out that grammatically her two words could only be a reply to my asking why her mother had left me five hundred pounds. But it didn’t make any sense beyond this. No blood had been spilt. My pride had been hurt, that was true. But Veronica was hardly suggesting that her mother was offering money in exchange for the pain her daughter had caused me, was she? Or was she?

Tony says “no blood has been spilt”; and yet we are told that Adrian slit his wrists. I have referred to a single, central, hidden plot device. Note how the climbing plants—the pain Veronica caused, the lack of blood spilt, the bequest, Tony’s wounded pride—wrap conveniently, easily, around the trellis, the hidden plot device, that being Tony’s self-interest. It doesn’t give too much away to tell you that reality’s fiction was not so favorable to Tony’s moral self-regard.

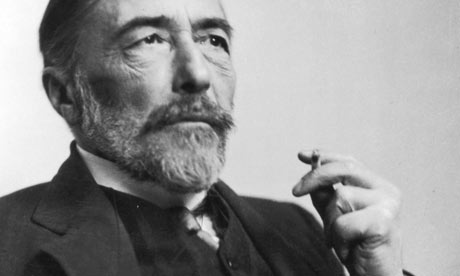

Tony is not extraordinary. He is average. His averageness is put on display in subtle ways that demonstrate my averageness. Think Tony is unusually pesky in trying to find the truth behind the bequest? Well, Barnes’ storytelling is arresting; I could not quit the story; so maybe I am as pesky as average Tony. Moreover, if Tony is average, and he formulates and re-formulates his fictions about himself in ways always founded on his self-interest, and his re-formulations seem plausible when I view them from his perspective, what does that say about me? Our identities are collections of stories about ourselves, and our stories are manically, madly, reflexively wrapped around the trellis of self-interest. “It is my belief,” said Conrad, under the mask of Marlow, “no man ever understands quite his own artful dodges to escape from the grim shadow of self-knowledge.”

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply