Some say that Charles Dickens invented Christmas as we know it. At least, that A Christmas Carol rescued the celebration from post-Cromwell piety and prompted the Victorians to introduce many of the traditions that we have come to cherish: the tree, the presents, the holly and the ivy, etc. A little less well known is the fact that A Christmas Carol rescued Dickens’ career as well, proving so popular that he would go on to write four more Christmas novellas, three of which had supernatural elements but only one of which was an out-and-out ghost story a la A Christmas Carol. Oddly enough, despite the lasting popularity of A Christmas Carol, one of the Victorian traditions which has been lost in our Halloween-saturated culture is the propensity for telling ghost stories on Christmas Eve. Christmas Eve being the darkest day of the year, both spiritually and daylight-wise, the time when the boundary between the living and the dead was at its thinnest and ghosts could roam free. (As an aside: regardless of what the haters say, early Christians were not somehow unaware that they were aligning Christmas Eve with Winter Solstice. It was not an arbitrary decision. If you are celebrating light coming into the world, when better to begin than on the day after the darkest day of the year?!).

Some say that Charles Dickens invented Christmas as we know it. At least, that A Christmas Carol rescued the celebration from post-Cromwell piety and prompted the Victorians to introduce many of the traditions that we have come to cherish: the tree, the presents, the holly and the ivy, etc. A little less well known is the fact that A Christmas Carol rescued Dickens’ career as well, proving so popular that he would go on to write four more Christmas novellas, three of which had supernatural elements but only one of which was an out-and-out ghost story a la A Christmas Carol. Oddly enough, despite the lasting popularity of A Christmas Carol, one of the Victorian traditions which has been lost in our Halloween-saturated culture is the propensity for telling ghost stories on Christmas Eve. Christmas Eve being the darkest day of the year, both spiritually and daylight-wise, the time when the boundary between the living and the dead was at its thinnest and ghosts could roam free. (As an aside: regardless of what the haters say, early Christians were not somehow unaware that they were aligning Christmas Eve with Winter Solstice. It was not an arbitrary decision. If you are celebrating light coming into the world, when better to begin than on the day after the darkest day of the year?!).

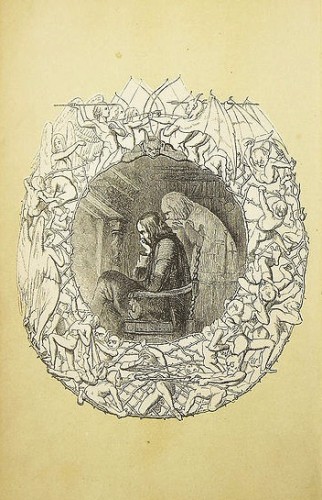

Anyway, Dickens would return to the ghost story model for his final Christmas novella, 1848’s The Haunted Man or the Ghost’s Bargain. It’s a bit more grisly than A Christmas Carol, and while certainly less iconic, contains an explicitly Christian potency that cannot be ignored (or is ignored for that reason…). It is the story of a lonely chemist named Redclaw for whom Christmas serves as it does for many people, as a reminder of past hurts and regrets. On Christmas Eve he is visited by a Phantom, who offers to “cancel his remembrance” of his deepest “wound and sorrow,” which set him on his path to solitude: the loss of his beloved to his closest friend, roughly twenty years in the past. He eagerly accepts the ghost’s offer, even the caveat that he will have the power to make others forget their most painful memories as well. Redclaw initially believes that this will be a blessing to all those who are haunted by their past, but soon discovers that the experiences and feelings he erases when he comes into contact with others are precisely those which are associated with love. That you cannot undo one without affecting the other. Needless to say, it’s a very powerful parable about suffering and its redemption. You can read the whole thing, for free, here.

One of Redclaw’s caretakers is a woman named Milly William, who appears to have the opposite effect on people as Redclaw. She graciously cares for the uncared for, spreading love and compassion wherever she goes, while Redclaw diminishes it, stoking the flames of entitlement and discord, believing, at first, that he is helping them. At the climax of the novella, after Redclaw has realized the true nature of his terrible bargain and repented, we learn the secret of Milly’s gift. By my estimation it is one of the most beautiful and touching, not to mention (explicitly) cruciform passages that Dickens ever composed. Spoiler Alert:

“It happens all for the best, Milly dear, no doubt,” said Mr. William, tenderly, “that we have no children of our own; and yet I sometimes wish you had one to love and cherish. Our little dead child that you built such hopes upon, and that never breathed the breath of life — it has made you quiet-like, Milly.”

“I am very happy in the recollection of it, William dear,” she answered. “I think of it every day.”

“I was afraid you thought of it a good deal.”

“Don’t say, afraid; it is a comfort to me; it speaks to me in so many ways. The innocent thing that never lived on earth, is like an angel to me, William.”

“You are like an angel to father and me,” said Mr. William, softly. “I know that.”

“When I think of all those hopes I built upon it, and the many times I sat and pictured to myself the little smiling face upon my bosom that never lay there, and the sweet eyes turned up to mine that never opened to the light,” said Milly, “I can feel a greater tenderness, I think, for all the disappointed hopes in which there is no harm. When I see a beautiful child in its fond mother’s arms, I love it all the better, thinking that my child might have been like that, and might have made my heart as proud and happy.”

Redlaw raised his head, and looked towards her.

“All through life, it seems by me,” she continued, “to tell me something. For poor neglected children, my little child pleads as if it were alive, and had a voice I knew, with which to speak to me. When I hear of youth in suffering or shame, I think that my child might have come to that, perhaps, and that God took it from me in His mercy. Even in age and grey hair, such as father’s, it is present: saying that it too might have lived to be old, long and long after you and I were gone, and to have needed the respect and love of younger people.”

Her quiet voice was quieter than ever, as she took her husband’s arm, and laid her head against it.

“Children love me so, that sometimes I half fancy — it’s a silly fancy, William — they have some way I don’t know of, of feeling for my little child, and me, and understanding why their love is precious to me. If I have been quiet since, I have been more happy, William, in a hundred ways. Not least happy, dear, in this — that even when my little child was born and dead but a few days, and I was weak and sorrowful, and could not help grieving a little, the thought arose, that if I tried to lead a good life, I should meet in Heaven a bright creature, who would call me, Mother!”

Redlaw fell upon his knees, with a loud cry.

“O Thou, he said, “who through the teaching of pure love, hast graciously restored me to the memory which was the memory of Christ upon the Cross, and of all the good who perished in His cause, receive my thanks, and bless her!”

Then, he folded her to his heart; and Milly, sobbing more than ever, cried, as she laughed, “He is come back to himself! He likes me very much indeed, too! Oh, dear, dear, dear me, here’s another!”

Then, the student entered, leading by the hand a lovely girl, who was afraid to come. And Redlaw so changed towards him, seeing in him and his youthful choice, the softened shadow of that chastening passage in his own life, to which, as to a shady tree, the dove so long imprisoned in his solitary ark might fly for rest and company, fell upon his neck, entreating them to be his children.

Then, as Christmas is a time in which, of all times in the year, the memory of every remediable sorrow, wrong, and trouble in the world around us, should be active with us, not less than our own experiences, for all good, he laid his hand upon the boy, and, silently calling Him to witness who laid His hand on children in old time, rebuking, in the majesty of His prophetic knowledge, those who kept them from Him, vowed to protect him, teach him, and reclaim him.

COMMENTS

5 responses to “Charles Dickens’ Other Christmas Ghost Story: “The Haunted Man””

Leave a Reply

The best Christmas story ever, and even for how often I’ve read the story I saw more after reading your beautiful introduction, it should be with all editions, thank you!

Dave, this is incredible stuff. I can’t wait to read the whole story.

The link to the story now works! Sorry about that.

This excerpt is teaching us how to take our trials and use them for good. Thanks for sharing this book; i never heard of it!