NPR has picked up on a strand of Dexter‘s sixth season that is asking all the right kinds of questions. The show, which stars Michael C. Hall as Dexter, imagines a killer gone karma, a criminal who (now) exacts justice by principle, killing killers to keep them from killing the innocents. The premise itself seems to make very non-Christian value judgments on the world, mainly that there are killers and non-killers, that there are those who act by principle and those who do not, that there is a universal ethic to which all are accountable and by which few miss the mark. On the flip side, though, Dexter’s role is one which utterly subverts and complicates the notions of law-fulfillment and retributive justice. As a killer himself, his own karmic punishment is suspended while his vigilante operation of justice brings forth the reckoning on others. The ethic by which he renders justice, is the retributive force which also hangs over his head. In an odd way, he is simul iustus et peccator: a man divided, justified and sinful.

NPR has picked up on a strand of Dexter‘s sixth season that is asking all the right kinds of questions. The show, which stars Michael C. Hall as Dexter, imagines a killer gone karma, a criminal who (now) exacts justice by principle, killing killers to keep them from killing the innocents. The premise itself seems to make very non-Christian value judgments on the world, mainly that there are killers and non-killers, that there are those who act by principle and those who do not, that there is a universal ethic to which all are accountable and by which few miss the mark. On the flip side, though, Dexter’s role is one which utterly subverts and complicates the notions of law-fulfillment and retributive justice. As a killer himself, his own karmic punishment is suspended while his vigilante operation of justice brings forth the reckoning on others. The ethic by which he renders justice, is the retributive force which also hangs over his head. In an odd way, he is simul iustus et peccator: a man divided, justified and sinful.

I am reminded of Kierkegaard’s notion of the “teleological suspension of the ethical,” the idea that one’s ethical framework, the shoulds and oughts of life, are suspended or put on pause in the moment of faith. Kierkegaard, with his Abrahamic knight of faith, makes room for faith that surpasses the quid-pro-quo of retributive justice and biblical law. Faith, for Kierkegaard, bends the fence-wire of universal morality and gains access to the absolute. Faith suspends the ethical by surpassing it.

Faith is precisely this paradox, that the single individual as the particular is higher than the universal and is justified over against the latter not as subordinate but superior to it, yet in such a way, mind you, that it is the single individual who, after having been subordinate to the universal as the particular, now through the universal becomes the single individual who as the particular is superior to it. Faith is this paradox that the single individual as the particular stands in an absolute relation to the absolute (Fear and Trembling, 48).

It is weird to talk about Dexter’s suspension of the ethical as a move of belief, though, precisely because this article highlights Dexter’s expressed unbelief in any religious system. It is also strange because Dexter, as the symbol of a more Perfect and Exacting Law, the reckoner that the police could never be, is coming to grips with the Law’s impasse: faith. Through murdering religious extremists, who believe that they are, yes, justified by faith and not works of the law universal, Dexter finds a daunting gap between his deductive (or scientific, as the article calls it) reasoning and faith-based response to the call of God.

Granted, the episodes may be pointing at these leaps of faith as the dangerous folly and foolishness of belief systems in general. Like the article says, “Obviously, they are taking a stance by choosing the killers to be religious fanatics.” On the other hand, it also seems to point the gun back on Dexter, asking him some questions, namely, who exacts justice here? And who is absolved? What deep-rooted implications does Dexter’s retributive law evoke? And what does this retribution solve? Thus maybe, as the writer decries, “It will be very disappointing if Dexter ends up a believer” because that’s the only place left to go…

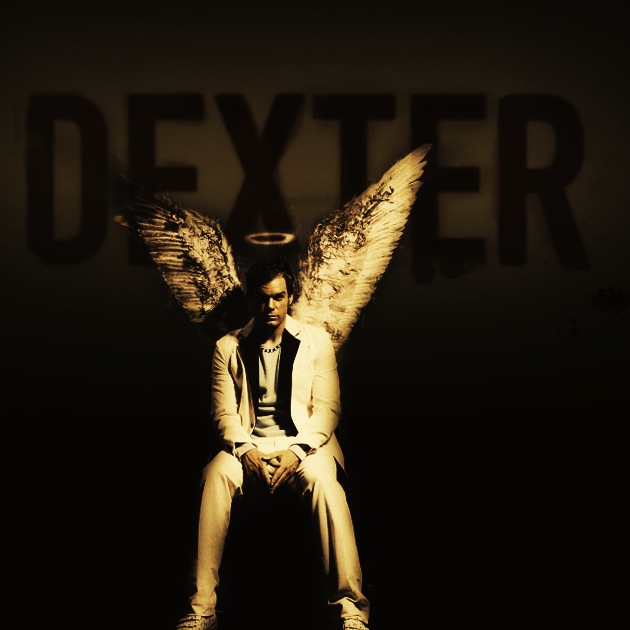

I imagine many of you are familiar with the Showtime hit series Dexter, now in its sixth season. If you are not, picture this: a serial killer turned avenger, played masterfully by Michael C. Hall, kills only those murderers who have escaped criminal justice.

Hall plays Dexter Morgan, a lovable, blood-splat analyst for Miami Metropolitan Police, who makes sure his victims “deserve” to die. He only kills after confirming they are murderers themselves. As part of his gruesome killing ritual, Dexter confronts each murderer with photos of his/her victims.

You end up rooting for a killer who tramples all notions of a working justice system. His logic is simple: if you kill an innocent person you deserve to die. Period.

Every season Dexter confronts a soul brother, another serial killer. The difference between Dexter and his victims is that he has tamed his “dark passenger,” the killer instinct that drives him relentlessly to murder. Maybe “tamed” is too strong a word. He has compromised, turning his killer instinct into a force for the good. Or, at least, he’s turned it into a force for justice where ordinary justice has failed.

This season is particularly interesting. For the first time, Dexter, an atheist who bases his actions on a logical, deductive approach, faces faith; the killers are acting in the name of their own distorted version of Christian faith, and believe to be completely justified. Their role is to bring the end of the world by precipitating the actions depicted in Revelation. Clearly, the show is a parody of faith-based murders that have stained the history of civilization, and still do. In particular, it skewers apocalyptic sects, a topic I examined in my book The Prophet and the Astronomer: Apocalyptic Science and the End of the World.

In a conversation between Dexter and Brother Sam, an ex-con turned-earnest-preacher, the issues are laid bare. Brother Sam says: “I can’t prove to you that God exists; but science can’t prove that God doesn’t exist either.”

There you have it, the age-old argument between science and religion: the faithful claiming that you can only find God in ways that exist beyond the plane of scientific deductive thinking, while putting the burden of proof on the scientist, pointing out that science is good at proving what does exist, but has little to say about what doesn’t.

An atheist would reverse the argument and state that the burden of proof is on the believer. “If you are sure God exists, then prove it to me. I can’t find any evidence.”

Carl Sagan used to apply a similar logic to the question of extraterrestrial alien life when he said that “the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.” Quite often his quote is misused to explain why science can’t say anything about God: the fact that we have no “evidence” cannot be used to disprove His existence.

There is, however, a very crucial difference between using science to prove the existence of aliens and using it to prove the existence of gods. Aliens, weird as they might be, still follow the laws of nature, being creatures with a biochemistry and metabolic rates. They can interact with our sensors and thus be detected. Gods, on the other hand, are, by definition, beyond the laws of nature: they don’t interact physically with sensors and other detecting devices scientists may use to find out what’s “out there.”

At the crux of this argument is a fundamental incompatibility between scientific and faith-based reasoning. In a sense, Brother Sam’s logic says it all: to those who believe in supernatural presences in the world, a scientific discourse is useless. This may answer a question Dexter asked himself, which went something like, “you’d expect that in an age of science people would stop believing in the supernatural; but that’s clearly not happening.” Essentially, to the faithful, science has very little to say when it comes to the existence of God. They may take antibiotics and send email with their iPads, and they may find the pictures from the Hubble Space Telescope really amazing, but that’s about where it stops. When it comes to ultimate questions, religion has the upper hand.

You would expect that some sort of pacific coexistence could be achieved, whereby the faithful and the non-faithful agreed to disagree about their beliefs and ways of dealing with reality and life. If you believe in God go on ahead believing, and if you don’t, don’t. Unfortunately, the two worldviews clash too often in everyday life, leading to serious political, educational and even life-threatening disputes.

The separation of state and church should take care of some of this. In practice, it doesn’t. Things get contentious when religion attempts to influence public policy or school curricula. (Of course, the faithful would perceive this as from a mirror, saying that things get contentious when atheists try to control what their kids should learn in school. It’s concerning that the solution is often home schooling, which takes away any exposure a child might have to different points of view.)

On TV, this clash was portrayed in a funny conversation — which I paraphrase here — between Dexter and the Mother Superior running the religious school where he wanted to enroll his little boy:”You are a Catholic, right?”

“No, I’m not.”

“Protestant?”

“Nope.”

“Jewish?”

“No.”

“Muslim, then?”

“Sorry, I don’t believe in … anything.”

To the faithful, not believing simply doesn’t make sense. They are much more forgiving of someone of a different faith than of someone with no faith at all. Atheists are at the bottom of the social chain.

I am not sure where the writers of Dexter will go as the season progresses. Obviously, they are taking a stance by choosing the killers to be religious fanatics. On the other hand, Dexter is also a killer. And he is godless. One kills for God, the other in the name of his own subjective sense of justice. Both are wrong. I’m hoping that, at least on TV, a compromise of sorts will be achieved.

It will be very disappointing if Dexter ends up a believer.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=toYzUtZdYUk&w=550]

COMMENTS

One response to “Dexter, Retributive Justice, and Knights of Faith”

Leave a Reply

Isn’t the empty tomb proof? I remember a debate that involved Christopher Hitchens vs Lane Craig. In my opinion Hitchens lost the debate in large part due to the empty tomb. After going through the possible scenarios (i.e. stolen body, fainting on the cross, etc) the only reasonable explanation was that Jesus had in fact risen from the dead.