A lengthy and very absorbing look at the subject of snobbery by Mark Oppenheimer over at Slate, “The Unholy Pleasure: My Life-Long Recovery From Snobbery.” Oppenheimer gives his own “testimony” in regard to the subject, shedding light on a number of the contradictions at the core of the issue. The article functions as a timely reminder that identity formation, to the extent that it’s a matter of security/insecurity, is inevitably a mask for self-justification. And while I don’t buy his claim that snobbery is fundamentally other-centered (others are only important in this schema to the extent that their attitudes and affections are a comment on you), the description of how judgmentalism turns against itself is spot-on. In fact, his general conflictedness about it all rings very true, and probably a bit too close to home. He may fail to mention explicitly the phenomenon we’ve come to recognize as “reverse snobbery” – that is, that snobbery is by no means a strictly rich or educated problem – but much of that is implied. Yet what’s truly remarkable here is the strikingly Gospel note on which Oppenheimer ends. A mention of God – gasp! – and in light of the contrite possibility that he may never change. Which, naturally, is par for the course, as far as Loomis grads go…, ht CB:

It is not unusual for snobberies to begin as self-defense—they are almost necessarily the province of minority groups worried that they might any day be vanquished: The landed English were surrounded by the peasants, the educated Ivy Leaguers by hoi polloi. Beneath the airs of superiority one can quickly discern the grounding of insecurity. After all, if the war comes, sheer numbers dictate that the snobs will lose. And given how much of the snobs’ privilege is unearned, their snobberies can also be seen as strategies of obfuscation, enabling them not to see the important injustices that their cherished order perpetrates…

But self-protective armor can be used in the offensive, too; judgment nearly always turns judgmental. Nobody likes to relinquish a snobbery, even when it becomes safe to venture forth without it…

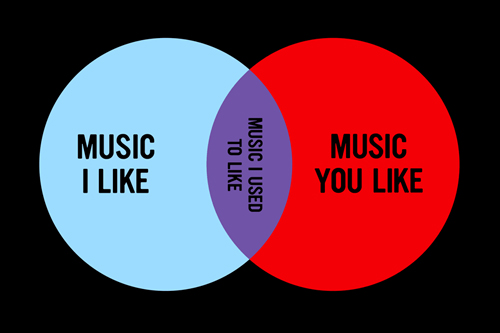

Snobbery is the most self-aggrandizing of dispositions, but it is not self-centered. Somebody who truly does not care what other people think—we might call her an eccentric—is not a snob, even if she bears traces of elitism. My friend George, for example, is famous for wearing bowties and blazers everywhere, even to casual brunches. He attended all the fanciest schools, was a fencer in college, and is a partner in a white-shoe Boston law firm. But he is so clearly more interested in self-expression than in what other people think of him that nobody would dare call him a snob. He’s not trying to prove anything by how he lives; he just cannot imagine living otherwise. A man who wears a bowtie to brunch on a Sunday morning is almost inviting derision, and it is a sign of his supreme self-confidence that he persists in doing so. The snob, by contrast, can never quite forget what other people think of him. That’s why it is very difficult to be a true snob before the age of 9 or 10.

…The next stage, the one I reached in third and fourth grade but began to perfect in fifth, is the abstraction of these principles, the infusion of them with moral judgment—the decision, for example, that using big words makes me a better person even if there is no obvious reward for doing so, or perhaps because there is no obvious reward for doing so. A child must reach a certain age before he can decide that rejection is the proof of his superiority…

I have long wondered how to make sense of snobbery’s many faces. Wherever snobbery can be found, it is evidence of insecurity, even emotional poverty; and yet it is frequently one of life’s great pleasures…

The problem, of course, is that after a while the snobbery game, like any game played consistently over many years, becomes quite serious. Just as there are no true “recreational” golfers, there is after a while no such thing as a recreational snob. The judgmentalism moves to the fore, and the snob really begins to see people as mere butterflies, objects for classification…

Snobbery is ultimately a dysfunction, and if my daughters were to lose potential close friendships, and someday lovers or partners, because of the trivia they imbibed, via their father, from The Official Preppy Handbook and Class, then I would have a lot to answer for. And once you learn snobbery, it is very hard to unlearn. They would be wrecked for life, like me.

Also, of course, snobbery is immoral. It is unkind, and frequently vicious, and built upon lies about what other people are really like. And yet I am not convinced that I can give up snobbery so quickly… For after all, snobbery is one of the great midwives of human closeness. Almost nothing I can think of unites two people better than shared snobberies…

I sometimes ask myself if there are those who truly think that all people are equal, who have no problem not saying anything at all if they can’t say anything nice. I think I have met people like that; from what I can tell, there seem to be some in the Midwest. They go through life not judging, not condescending. I suppose they are close to God. They certainly have an easier time making friends…

I do wonder if I can ever change; I cannot decide if I even want to. I think the best I can hope for is to see my snobbery as a set of neutral, amoral preferences, most of them arbitrarily chosen. The art critic Dave Hickey has written that good taste is just the residue of someone else’s privilege, and I have to admit that’s right. God—the universe—the perfect good—whatever you want to call the arbiter of moral truth—does not care whether my floors are parquet or covered by wall-to-wall carpeting. That I do care is a fact about me, best confronted and managed. It is not to be exalted, but it cannot be honestly denied.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ftEyTRNTKN0&w=600]

COMMENTS

One response to “Snobby Snobs and Their Snobbish Snobbery”

Leave a Reply

Those last couple sentences are brilliant.