Way back on Christmas Eve of 2013, The Guardian ran a piece by photographer Chris Arnade under the provocative title, “The People Who Challenged My Atheism Most Were Drug Addicts and Prostitutes.” It remains one of the best and most heartening things I’ve read on that intersection. Arnade recounts how thoroughly his unbelief was challenged after quitting his Wall Street job to photograph addicts in the South Bronx:

When I first walked into the Bronx I assumed I would find the same cynicism I had towards faith. If anyone seemed the perfect candidate for atheism it was the addicts who see daily how unfair, unjust, and evil the world can be.

None of them are. Rather they are some of the strongest believers I have met, steeped in a combination of Bible, superstition, and folklore…

But he went further than mere surprise. “Soon I saw my atheism for what it is: an intellectual belief most accessible to those who have done well.” Woah! I couldn’t believe his guts then, and I can’t believe them now. In a world in which ‘de-conversion’ narratives seem to grow sexier with each passing day (just peruse latest issue of the New Yorker if you don’t, er, believe me), no one wants to surface the privilege component—to say nothing of social class. But it’s getting harder and harder to ignore.

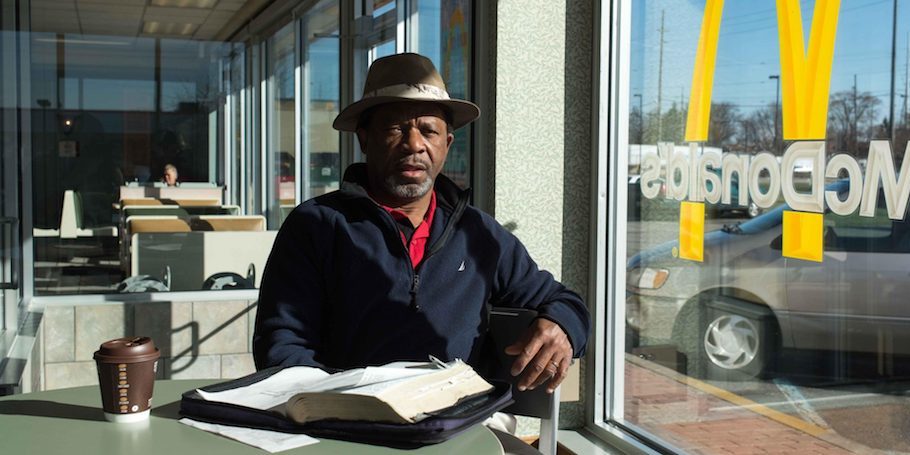

Anyways, on June 4th, Arnade’s photos will finally be published in book form. The faces he captured thankfully extend far beyond the South Bronx into all the overlooked crannies of American life, where dwell what Robert Capon calls “the last, the least, the little, and the lost” (or Tyrion Lannister the “cripples and bastards and broken things”). The title of the collection is Dignity: Seeking Respect in Back Row America, and we were fortunate enough to receive an advance copy. I cannot recommend it highly enough, not only for the stunning images, but for the essays that accompany them. I mean, the first chapter alone is titled “If You Want to Understand the Country, Visit McDonald’s.”

Anyways, on June 4th, Arnade’s photos will finally be published in book form. The faces he captured thankfully extend far beyond the South Bronx into all the overlooked crannies of American life, where dwell what Robert Capon calls “the last, the least, the little, and the lost” (or Tyrion Lannister the “cripples and bastards and broken things”). The title of the collection is Dignity: Seeking Respect in Back Row America, and we were fortunate enough to receive an advance copy. I cannot recommend it highly enough, not only for the stunning images, but for the essays that accompany them. I mean, the first chapter alone is titled “If You Want to Understand the Country, Visit McDonald’s.”

Then there’s chapter three, entitled “God Filled My Emptiness,” in which Arnade reiterates and expands on some of his earlier findings. You’ll have to read the whole thing to grasp the full impact of what he’s saying (and a truncated version is now available online), but here’s one passage that stopped me in my tracks, an indelible picture of what the church can be and sometimes, by the grace of God, even is. Spoiler alert: it has almost nothing to do with exhortation:

“In [the minds of many back row Americans] the only places on the streets that regularly treat them like humans, that offer them a seat to sit in, an ear to listen, and really understand their past are churches. They are everywhere. Small churches that have come in and taken over a space and light it up on Sundays and Wednesdays. They walk inside the church, and immediately they meet people who get them. The preachers and congregants inside may preach to them, even judge their past decisions, but they don’t look down on them. They have walked the walk and know the shit they are going through, not from a book, not from a movie, not from an article, not from a study, but from their own life or the lives of their friends. They look like them, and they get them.

There are rules to follow if you join, but they don’t require having your paperwork in order, having proper ID. They don’t require getting grilled about this and that. They say, ‘Enter as you are,’ letting forgiveness wash away a past that many want gone. You are welcome as long as you try. The churches understand the streets, understand everyone is a sinner and everyone fails. In their mind, the rest of the world—the courts, the hospitals, the rehab clinics, the welfare office, police stations, and even some of the nonprofits and schools (especially the universities that won’t even let you on campus without the police being called)—doesn’t understand that. That cold, secular world of the well-intentioned is a distant and judgmental thing. That world has given them seemingly nothing but pain.

The churches are also the way out of addiction, a way to end the cycle. The few success stories told on the streets are of relatives, friends, or spouses who found God… and moved away: ‘Princess met a decent man who was dedicated to the Scripture. She got straight, got God, and last we heard was on a farm upstate.’ ‘Neceee went to her grandmother’s and found God, and she now has her one-year chip.’

This is how it is on the streets. Faith is the reality and a source of hope. Science is the distant thing that doesn’t necessarily do much for you.

© Chris Arnade, “Dignity.” Publisher: Sentinel, 2019.

I can’t help but reproduce one more portion, in which Arnade highlights the enormous disparity between where he had come from in the ‘front row’ and his experience on the streets:

Like most in the front row, I am used to thinking we have all the answers. On Wall Street, there were few problems we couldn’t solve with enough smarts, energy, audacity, or money. We even managed to push death into the distance; with enough research and enough resources—eating right, doing the right things, going to the correct medical specialist—the inevitable could be delayed, and mortality could feel distant.

With a great job and a great apartment in a great neighborhood, it is easy to feel we have nothing for which we need to be absolved. The fundamental fallibility of humans seems outdated, distant, and confined to a few distant others. It’s not hard to imagine that you have everything under control.

The tragedy of the streets means few can delude themselves into thinking they have it under control. You cannot ignore death there, and you cannot ignore human fallibility. It is easier to see that everyone is a sinner, everyone is fallible, and everyone is mortal. It is easier to see that there are things just too deep, too important, or too great for us to know. It is far easier to recognize that one must come to peace with the idea that ‘we don’t and never will have this under control.’ It is far easier to see religion not just as useful, but as true.”

COMMENTS

3 responses to “The Only Places on the Streets That Understand”

Leave a Reply

Wow DZ, great stuff. I followed Chris on Twitter for a long time. Find him fascinating. Thanks for the tip on this book. I’m part of a group in Tuscaloosa forming a new congregation (“new” … we’ve been at this 5+ years). The experience has really opened my eyes and changed my mind about what a church (especially in an old Southern town) is really called to do and who they are sent to serve.

Poverty has traditionally been linked to high levels of religiosity. See Pippa Norris and Ronald Ingelhart’s “Sacred and Secular”.

DAVE