I believe God made me for a purpose, but he also made me fast. And when I run I feel His pleasure.

– Eric Liddell

Stop me if you’ve heard this story before…. A young underdog struggling to find their voice in a backwards town where they don’t seem to fit in. They want to be an artist, or a scientist, or a runner, or a voyager, etc., but they can’t because “that’s just not how things are done around here.” Maybe they move to the big city to finally do what they feel compelled to do. Or they stay put—either way. Perhaps there is a mentor figure who comes along to teach them their craft. They finally live out their calling, it seems, and become who they feel they really are. Perhaps, along the way, the naysayers are proven wrong and their hometown recognizes them for their extraordinary gifts. End of story, happily ever after.

This basic plot is so ubiquitous nowadays, it’s a little insane: Moana, Creed, October Sky, Footloose, Star Wars, Supergirl. I could go on, but you get the point. The protagonist has a calling and we get to watch them become what they’ve always dreamed of being. What they finally do is what they were created to be all along. They are gifted and, we might say, special. What they do corresponds perfectly to who they are. Anything short of that is an unacceptable failure. I love these stories—don’t get me wrong—because they are inherently hopeful, as they rightly suggest that the world and our lives can actually change.

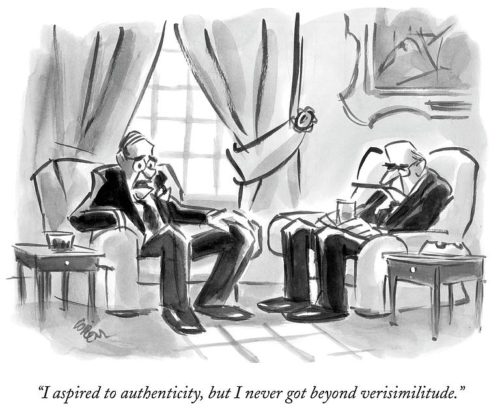

But these stories of finding happiness by becoming yourself also reflect our current zeitgeist, what philosopher Charles Taylor called the “ethics of authenticity.” Its predominant moral imperative is simply to be true to yourself (and no one else). Or as Taylor described it, “There is a certain way of being human that is my way. I am called upon to live my life in this way, and not in imitation of anyone else’s life…. If I am not [true to myself], I miss the point of my life; I miss what being human is for me” (p. 29). Everyone is unique, and it is precisely the difference between persons that has moral significance. What’s right for me may not be right for you; it’s up to you to choose. The “right” thing to do isn’t measured by a code of right and wrong but whether you are authentically you in your actions.

The ethics of authenticity is not driven by an external code of right or wrong (however that might be defined), but by the particularities of what makes you, you. There is no universal imperative by which all humans must live if they desire to flourish; personal happiness can only be achieved by fulfilling one’s unique potential. “You do you,” so to speak. So far as I can tell, ascribing such moral import to the differences between individuals is an entirely new development in the history of western thought.

Lee Lorenz

The ethics of authenticity flatten and narrow the meaning of our lives to what we can imagine for ourselves, opening us to the possibility of unforeseen heights of achievement and the corresponding lows of personal failure. The modern downsides of such a “me” morality are well documented here on Mockingbird (loneliness, anxiety, “alternative facts” and the loss of moral institutions, depression, etc.). My issues with it are far more foundational. It is incompatible with Christianity’s understanding of humanity.

To put it bluntly: What if you aren’t actually special? With all due respect to the aforementioned Eric Liddell, I have a difficult time finding in scripture someone for whom God’s calling in their life had any relation to their intrinsic aptitude, resources, skills, or worth. Abraham was ungodly. Moses was a terrible public speaker. Israel was chosen because it was smallest of all the nations. King David was born a shepherd. Peter was a fisherman and an impetuous knucklehead. Paul persecuted the Church and, when it came to actually doing what God called him to do, he could be a quarrelsome jerk. Time after time, God chooses the idiots, the weak, the lowly, and the despised to do his bidding (1 Cor. 1:26-29). If there is a special reason why “the ocean” chose you (as in Moana), it’s probably not very flattering.

Even if we were to allow for the possibility that there is something unique and special about you, to which you should be faithful, would you even know it? Scripture doesn’t exactly suggest that self-knowledge is something we possess. In the face of the demand to be ourselves, the cry of Paul in Romans 7 is inevitable. What we do and why we do it is a mystery to us (v. 15). If anything, a fearless inventory of our actions produces self-loathing (for good and ill). If there is a “good that dwells in me” we do not know it (v. 18). If there is a hidden self to which we must be true, it is enslaved and held captive by powers we cannot overcome (v. 23). The picture Paul paints is a bleak one, but I think experience vindicates his pessimism. The relative stability of one’s identity has been vastly exaggerated. Who we are, at any given moment, is so mailable as to render the concept ludicrous. Making your identity the basis of your ethics is like using Google Maps without it (or you) knowing your location.

Whether we’ve realized it or not, the ethics of authenticity have won the day, or at least everyone I know (religious or not) sympathizes with its basic tenets. Discussions of one’s “spiritual gifts” are largely indiscernible from our cultural obsession with Meyers-Briggs or the Enneagram. We are gifted by God (supposedly) and its our job to “live into” that special giftedness.

It is true that our “authentic” identity is in Christ as we are adopted as sons and daughters of the Father, but I wonder whether this repackaging of the gospel might be yet another way in which the “quest for glory” (authenticity) is not extinguished but appeased. Fitted with this shiny, new, “Christian” identity, the old Adam readily perverts the gift of grace to make it yet another venue for self-righteous authenticity. We so much don’t want to be just another anonymous human that being a Christian becomes another attempt to satisfy the ethical imperative of authenticity.

It seems to me that the only way to avoid the gravitational pull of the ethics of authenticity is to preach something that sounds like nonsense to the modern ear: No one is special or unique in any meaningful way. God is wholly unconcerned with the niches and idiosyncrasies that we think make us different. If we have an identity to claim it is simply that of “sinner.” Other comparable words like “failure” and “idolater” are also acceptable. God loves sinners, and no one else. To be “righteous” is an identity given by God and not a possession.

The life of the sinner loved by God is not marked by depressive self-loathing, but self-forgetfulness, responding to the needs of the neighbor and the world. To be self-forgetful is turn one’s eye toward the community and those in need, rather than toward sanctified navel-gazing. Such a life is not a life of becoming who God created us to be, but sharing God’s indifference toward our sinfulness by becoming unrecognizable to ourselves. Instead of becoming more authentically ourselves, we become less and less ourselves. Or, as Paul put it, “It is no longer I who live but Christ who lives in me.” Our life is in Christ and not a self-derived authenticity. Perhaps the goal of the Christian life is not becoming a better version of you, but ceasing to be you altogether—losing your life to find it.

COMMENTS

5 responses to “The Ethics of Authenticity”

Leave a Reply

Fantastic!

Thank you so much for this. Today is the day we all have to trim the list of things we’re thankful for so we don’t flail when it comes to us around the table tomorrow. Pretty sure mine is going to be this blog post.

Medicine for the soul. I didn’t even know I needed this today. Just yesterday I was commenting to my wife (after hearing a TBN preacher speak about “your destiny” and “God making you into who you are” the night before) that I haven’t stressed about “missing God”, my “God given purpose”, etc for a while now. She and I agreed “God’s purpose” for our lives is whatever circumstance we find ourselves in and what we are doing at any given moment.

But you stepped up the game today. The whole ‘not-special-thing’ and being called by God NOT because of my intrinsic “aptitude, skills or worth” was VERY freeing. Good news to a guy who prides himself on his gifts, even though he’d like to think he doesn’t.

Amen, my friend

Ellery:

I hear you, regarding the TBN preacher’s ‘your destiny’ comment. For one thing, I’m so sick of hearing that phrase over and over again. The Christian life is not about YOU, or I. Where is the self-forgetting in ‘your destiny’, etc., etc..?

Right now, I am content with being both an anonymous human, and Christian. I tried being ‘important’ at them, and failed miserably.

Thanks so much for your comment, and to Charis for the whole blog post!

[…] what Charles Taylor calls “the ethics of authenticity” — there’s a unique way to be yourself that is up to you to discover and cannot be imposed on […]