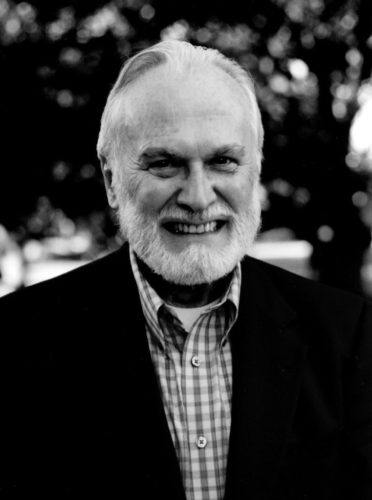

John L’Heureux’s latest short story, published recently in the New Yorker, tells of a woman who wants a sign from God…and receives one, just not in the way she expected. You can read the whole thing here.

It’s called “The Rise and Rise of Annie Clark.” Annie, a “capital-C Catholic,” is trying to measure her sanctity. She looks constantly for signs from above and wonders about the stigmata and imagines what it would be like to levitate, as only the holiest people can. At the same time, she is “a modern woman” who is “taking charge of her life.” As concerned with holiness as she is with right-ness, she argues with a waitress about a serving size of cheese; and she will not stand for her family’s irreverence. Desperately seeking affirmation from God, she scrutinizes the events of her life, and wonders if this or that could be “a sign”: “She wonders now if she is pleasing to God. If so, she’d like some evidence of it; nothing big like the saints had, just a little something to keep her going.” She reads the tea leaves of others’ lives, too, telling her sister what God does or does not intend: all of which looks a lot like spirituality but is really just a means by which she tries to control or make sense of things.

In an interview about the story, L’Heureux explains Annie’s conflict: though she talks boldly about how “God’s ways are not our ways,” in fact, she harbors a deep distrust in the mystery of love divine. Usually, she can be found trying “to strong-arm God, to elicit verifiable evidence of her sanctity,” which “not only makes a mockery of grace; it also makes genuine spirituality impossible for her.” Trying her damnedest to do God’s will, Annie buckles down: she joins — then quits — a convent; marries, has four children, and, when they become too impudent for her, abandons them for a purer life in Florida.

In an interview about the story, L’Heureux explains Annie’s conflict: though she talks boldly about how “God’s ways are not our ways,” in fact, she harbors a deep distrust in the mystery of love divine. Usually, she can be found trying “to strong-arm God, to elicit verifiable evidence of her sanctity,” which “not only makes a mockery of grace; it also makes genuine spirituality impossible for her.” Trying her damnedest to do God’s will, Annie buckles down: she joins — then quits — a convent; marries, has four children, and, when they become too impudent for her, abandons them for a purer life in Florida.

She returns a few months later, utterly confused: “…everyone has turned on her. She is lost and she knows it. If only she could reclaim that moment of silence when she almost saw where it was that she stood in the eyes of God. Did she almost see that? Or did she deceive herself?” It’s the end of the story, and even now, she is measuring. Even now, she remains deeply anxious about her standing with God and continues seeking a spiritual metric by which to establish her righteousness or unrighteousness. She has accepted that she may not be as good a person as she once thought — but she wants to know how bad. In despair (or self-pity), she returns to church and kneels before the Blessed Virgin and spirals into surrender…and falls asleep.

Then comes the climactic moment:

…Annie sleeps a good, unfeeling sleep. She knows nothing. She wants nothing.

Now slowly, gently, she rises in the air, kneeling upright as she ascends to a height of exactly three feet two inches, still sleeping soundly, aware only that she has surrendered, whatever that means. She knows nothing of what is happening to her.

…she is that tiresome Annie Clark, and without doubt she is kneeling on the empty air.

Yes: at last, Annie levitates. At last, she has her sign…and she is unconscious for its duration. Worse than not knowing what has happened is that it happened while she was asleep: in church. She wakes up embarrassed, perhaps a little ashamed. In all likelihood, she will stand, dust off her pants, and return home to pick up the shambles of her life, never knowing the miraculous event of which she was a part.

Is there a purpose to it? The narrator muses, “More likely, God is simply in one of His antic moods. It is not useful to examine this kind of thing too closely… Still, you have to wonder.”

The levitation cures nothing. Annie will never benefit from it. But perhaps, even so, it confirms what she has always longed for: her sanctity in God’s eyes — though now we see it comes apart from any conscious movement of hers (and at a moment when, in the eyes of her peers, she is least worthy, having recently abandoned her family, and showed no remorse, and been fired from a job). To L’Heureux, the levitation hints at the way God gives gifts; not transactionally but freely. By grace, in other words. According to L’Heureux, “grace is given freely, it is not some kind of celestial merit badge…Grace, we are told, cannot be earned. It is given with no strings attached.” Despite her best efforts, Annie’s life continues to defy her optimistic expectations. She may fairly read her life’s story as a perplexing “rise and fall” or even as a “fall and fall”; only the omniscient narrator knows the whole truth.

Like Annie, few of us rarely know what’s going on in life; do not know where we’re headed, whether we are rising and rising, or falling defenselessly. We do not know our life’s trajectory, how we are perceived by others, or whether the choices we make are right. Life is confusing more often than it’s not, and sometimes even more so when we entertain the idea that an omnipotent God is in charge of it all. There are times when we can trace the breadcrumbs of divine will: but more times when the breadcrumbs seem to have been consumed by birds of prey. In these dark woods of confusion, L’Heureux points us back to Job and God’s inquiry of him: “‘Where were you when I laid the earth’s foundations? / Who settled its dimensions? Surely you should know.’ Is there a touch of divine sarcasm here?”

“The Rise and Rise of Annie Clark” suggests that the woods of confusion are not only dark. Confusion means we are not the experts of our given field; it means we lack the ability to understand everything, and our capacity to control is sincerely wanting. It means we are captive to a process beyond ourselves, or, in the words of St. Paul, “captive to the Spirit.” Maybe what looks to be mere sound and fury is something else entirely — something, even, good. L’Heureux continues, “Grace is, I suppose, the ultimate mystery in God’s dealings with men and women.” Annie wanted certainty; what she gets, to her mind, is only mystery.

We all know an Annie Clark, if only when looking in the mirror. All she wanted was a sign, “just a little something to keep her going.” But imagine if she was awake while she levitated… On second thought, I’d rather not!

COMMENTS

3 responses to “In Praise of Confusion and John L’Heureux”

Leave a Reply

Wow CJ! Thanks for the synopsis. Love the picture of finding grace in all the wrong places.

Holy moly, what a post! And what a story! This made my day.