This one comes to us from Faith Perry.

Hi, my name is Faith. I’m in Room 22. Today I’m feeling anxious and confused. My goal for the day is to get the most out of groups.”

“Faith. Faith is feeling anxious and confused. Her goal for today is to get the most out of the groups. Anxious and confused. Tell us about it, Faith.”

I do not want to tell these strangers why I’m feeling anxious and confused. In fact, from the sheet of faces the staff handed to us, I just picked those two emotions because I thought they looked funny. That, and I really was confused about why I was not allowed to kill myself the day before and why I was talking to all of these strangers at 8:00 in the morning. Everything is foggy, and I made up that answer about groups. I don’t care about groups. I learned on the first day that “I want to learn from the groups” was the “right” answer to say to get to go home. It turns out that even in the psych ward, where all emotions and personalities are fair game, there are still right answers. And maybe I really am anxious to be here. It’s not like I have just been stripped away from everything I know, placed in handcuffs, and left to spend the night in the emergency department alone and crying before coming here. Alone is a lie. There was one police officer who was unsure of what to do with my nervous breakdown and sat quietly by the door while offering to get me blankets or water from time to time. I had to have a police officer so I didn’t try to hang myself with the bed sheets. Figures.

I do not want to tell these strangers why I’m feeling anxious and confused. In fact, from the sheet of faces the staff handed to us, I just picked those two emotions because I thought they looked funny. That, and I really was confused about why I was not allowed to kill myself the day before and why I was talking to all of these strangers at 8:00 in the morning. Everything is foggy, and I made up that answer about groups. I don’t care about groups. I learned on the first day that “I want to learn from the groups” was the “right” answer to say to get to go home. It turns out that even in the psych ward, where all emotions and personalities are fair game, there are still right answers. And maybe I really am anxious to be here. It’s not like I have just been stripped away from everything I know, placed in handcuffs, and left to spend the night in the emergency department alone and crying before coming here. Alone is a lie. There was one police officer who was unsure of what to do with my nervous breakdown and sat quietly by the door while offering to get me blankets or water from time to time. I had to have a police officer so I didn’t try to hang myself with the bed sheets. Figures.

Through my fog I notice I am wearing scrubs. Not the fancy kind with flowers or anything like that. I am wearing ugly, oversized, baby-blue scrubs. Perfect. I’m a real-live, bona fide crazy person. Complete with scrubs. About half of this room of crazy people is also wearing scrubs. At least I fit in. I am a part of something … albeit it’s the psych ward, but I’ll take what I can get.

I know now that I’ll never share a bond with any group quite like the one we all shared during that time again. We were all in it together. We were all in what I called a “mandatory time out from life” in the psych ward, figuring out our (explicit word) with strangers. We joked about how the Tide Pod Challenge was still going strong, but we were the ones that society deemed “crazy.” Now may be a good time to mention that my roommate in the psych ward heard voices, someone down the hall couldn’t come down from a manic high, and the person next door stabbed someone. I’ll concede that we were all temporarily insane, but we all had a good time comparing medication side effects and talking about how bad the coffee was. When someone left us to go back outside our holding cell, we wished them luck.

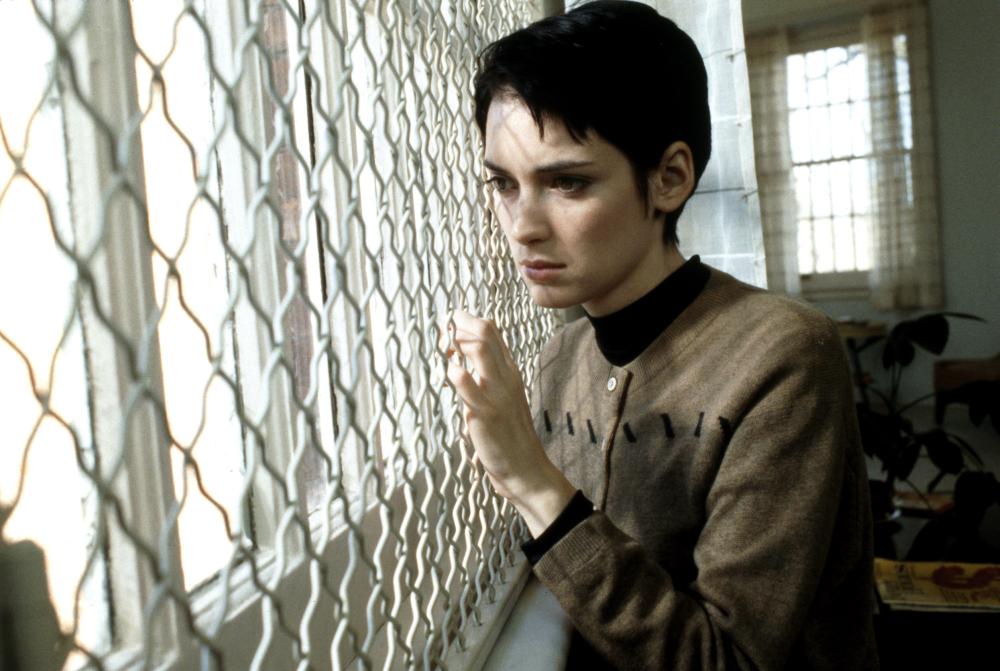

Good luck. It’s interesting to wish someone luck on day-to-day living. Your time out from life is over. Good luck. You have the tools to function, you’re back on the right track, you can do this, we believe in you, we are excited for you, we hope to be there soon, see you on the other side. Good luck. But no one talks about life after a wished-for, attempted, or failed suicide. What happens once a person, who not long ago wanted to kill themselves, goes back out into life? What happens when they are deemed stable and sent into the world with a diagnosis in one hand and belongings in the other? Picture a movie poster here.

Good luck. It’s interesting to wish someone luck on day-to-day living. Your time out from life is over. Good luck. You have the tools to function, you’re back on the right track, you can do this, we believe in you, we are excited for you, we hope to be there soon, see you on the other side. Good luck. But no one talks about life after a wished-for, attempted, or failed suicide. What happens once a person, who not long ago wanted to kill themselves, goes back out into life? What happens when they are deemed stable and sent into the world with a diagnosis in one hand and belongings in the other? Picture a movie poster here.

I’m here to tell you that life after suicide is not much different than life before it, except that you didn’t expect it to happen. I expected my life to end. I said my goodbyes. I put my things in order. I cleaned my room and finished eating all the food in the cupboards without buying more. All that to say, I didn’t make any plans past February, when I was supposed to die, and I had no food in my house when I got home.

This could have been great. I had no plans. I could start doing things I wanted to do, pick up a new hobby, get in shape, see friends. I could buy good-for-you food, like kale. The problem is this: when a person comes out of the hospital, they still have the same mental illness that got them in there. That doesn’t change.

When I got out, I continued to have dark thoughts, days, and weeks. I still wasn’t 100% sure that I wanted to live. I struggled to catch up with school and work after my absence. I was medicated. I had a million side effects I didn’t know how to deal with. I was confused. I felt alone outside of my bubble of crazy people. And I still carried the weighted secret of depression with me like a lead chain. I was too tired to buy healthy food or go out because my depression did not go away.

I think this is a key point that is often missed in our society. Stories of suicide focus on the completed suicide. They focus on the relatives and friends of the lost person. They focus on their grief and loss. People neglect to talk about the other side of the story: if the person lives? Well, then that person is cured. Obviously. They’ve spent their time in the hospital and now they are cured. While this may occasionally be the exception, it is not the rule.

It does get better. And worse. And better. There was a time that I stayed in Room 22 and grudgingly talked to people about life. Now I want to talk to people who are struggling, people who are struggling with depression, people who don’t know how to help their loved ones with depression, and people who need to know that someone else has been there. I want to start the conversation. If you have a loved one who has a mental illness of any kind, do not assume that after a hospitalization, their problems have just gone away. They haven’t. Odds are, they need a friend more than ever.

If you or someone you know is struggling with thoughts of suicide, you can find help by calling the Suicide Hotline at 1-800-273-8255.

COMMENTS

5 responses to “After Suicide”

Leave a Reply

Thank you for this, Faith!

❤️

This is an excellent post.

I am also one, who attempted suicide, and had to spend some time in a psych ward. And the poster is right: even though you come out of the ward (usually with meds in hand), the depression and/or anxiety hasn’t magically disappeared. It is still there, lurking about.

Hey man I appreciate what you’re doing here. I dealt with severe depression for 8 years in my early childhood because of a nasty divorce and my father manipulating me to hate my mother. I had night terrors, sleepless nights, failed classes, self harmed, made 4 suicide attempts and writes suicide notes. I ran away one night after my father verbally abused due to him being a narcissistic father. The cops brought me home and I tried to take my life with a kitchen knife. My sister stopped me and my father called the police when they brought me to the local hospital where I was admitted into a psychiatric ward. At that time I was also on 100mg of Zoloft a day, my grandma recently passed and everything seemed dark and hopeless. After the psych ward I stopped taking my meds and I still struggled a few months after the psych ward. After I started going to therapy regularly and figured out that it was parental alienation from my father who was the cause of everything I begun recovering. Once I could understand my pain I could get past it. Just wanted to share my story one here in case anyone needs to relate. Thank you for putting these videos up to help people man. You absolutely have to have help to get out of that dark place and learn how to become stable again.