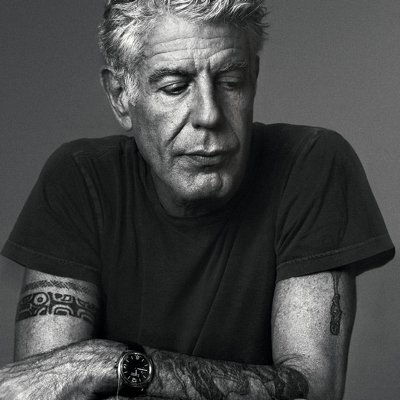

To say that I am a big Anthony Bourdain fan would be an understatement. I love everything he ever did. When my college boyfriend declared Alton Brown more entertaining and called Bourdain “depressing,” I was like: It’s not me, it’s you. We have to break up now.

I remember watching his episode of a pig being slaughtered in Louisiana. The cameraman captured the gathered faithful reciting the Lord’s Prayer right before the pistol rose to the head of the soon-to-be-eaten animal. Immediately following, the zydeco music kicked up. And I thought to myself, “That’s how we do it down here, folks.”

Of course, anyone with a nose to smell and a tongue to taste knew that Bourdain lived in an ocean of struggle. He could be angry, despondent, and euphoric all in one plate of food. It’s part of the reason we loved him. He brought other worlds into our living room without any pleasant edits. And that included the profound pain of his own heart.

I have written about suicide before for Mockingbird. I come from a family ravaged by it. But I do not want to address how Bourdain died so much as what I suspect really killed him.

I have a mentor who often says about ordained people, “Something bad happened to you if you want to be a priest.” Meaning that people are attracted to ministry as a means by which to fix what is broken. Maybe we come from tough family situations and/or we have an endless and neurotic need for love and attention.

I was once in a clergy conference where the speaker asked how many of the people in the room had a mother who often “took to bed” or who was actively an alcoholic. In other words, how many people had mothers that they felt they needed to take care of when they were children? Easily 75% of the people in the room raised their hands.

For these people, there was the hope that the Church might be the Mother that would care for them. This is, of course, not at all the way ministry works.

And it is not the way fame works, either. I do not know specifically what haunted Anthony Bourdain. Did he have a need for affirmation or encouragement? Or perhaps it was just the overwhelmingly human need for love. Perhaps he was caught in a black hole of despair that he saw no way out of. But fame, like the ministry, is not going to heal any deep wounds. In fact, it will exacerbate both.

We all long for fame on some level or another. Maybe we won’t be Anthony Bourdain. Perhaps we would really love to be the head of a company. Or the head pastor of our church. Or have more followers on social media. Or be the PTA president. But fame does not do what it promises. Because fame has an unquenchable desire to be fed. It solves none of life’s problems. Fame will take your mental illness, insecurities, and addictions and scare the hell out of you. Because now, instead of just you carrying the burden of yourself, it is entirely possible that the whole world will find out your deepest, darkest secrets. I cannot imagine the stress.

In this way, suicide makes an odd kind of sense. It is that exposure of all our brokenness to the world. It is this way of saying, “I can’t hold it all together. I give up completely. And I will do it in front of all you who have asked far too much of me.” Certainly, not every famous person will die by suicide. But I believe we would be shocked to know how many of them have considered it.

In truth, we were not made for fame. Being famous ultimately means being responsible for other people’s lives. It means taking on the pressures of the world. And it means being loved by people who do not really love you. Because they do not really know you. And this is the worst kind of love to be offered.

COMMENTS

11 responses to “On Anthony Bourdain: We Were Not Made to be Famous”

Sarah, I believe this might be your best yet! You have a remarkable gift that I pray you will always be able and willing to use! Go, girl, go!

I saw a quote this morning from Bourdain that made me think of Mockingbird: “The more I become aware of, the more I realize how relatively little I know of it, how many places I have still to go, how much more there is to learn. Maybe that’s enlightenment enough — to know that there is no final resting place of the mind, no moment of smug clarity. Perhaps wisdom, at least for me, means realizing how small I am, and unwise, and how far I have yet to go.”

Thanks for your thoughtful writing, I came to mbird.com today looking for some clarity or insight regarding Anthony Bourdain, suicide, and sadness. I’m glad you were here and took the time to write this and share it today.

I don’t understand why people are so quick to comment on a stranger’s depression, demons, and suicide. Chemical imbalances (if that was a factor) don’t care if you’re famous.

This kind of rhetoric worries me because suicide is way more complicated than this. It just seems like you’re trying to tame and name something that can’t necessarily be tamed and named.

Hey Charlotte,

I am certain that I am trying to understand something that’s can’t be understood. Unfortunately, my family history means that I am always trying to “understand” suicide. And for better or worse, I process through writing.

I know that brain chemistry has nothing to do with fame. I’ve lost too many people I love dearly to ever think that.

I hope I didn’t offend you. That’s the last thing I’d want to do.

Thanks for your reply. I don’t think I’m offended personally. My response to your piece was more out of curiosity. I’ve seen several people (mostly church leaders) this week write about suicide in ways that seem far-reaching.

If I was famous and a Christian and struggling with severe depression and suicidal thoughts and read this post, I would totally beat myself up for being famous. I would feel responsible for an illness that might plague me even if I wasn’t famous. I would wonder why I wasn’t Christian enough to escape my demons.

Also, I think people who are Christians but not famous might read this and think, “Thank God I’m safe, my children are safe, my loved ones are safe. We’re not famous, so it’s all good. Let’s all just not be famous forever so we can stay safe.”

So these are just my reactions to the piece. I think there are ways to talk about mental illness and suicide that don’t create these safe zones and unsafe zones.

On the other hand, people are talking and writing about these topics, and that happening in any capacity is good. Especially if it spurs conversations.

AMEN!

Would love to hear you, DZ and RJ talk more about this on the podcast!

Holy shit 582 shares!

Your writing is starting to feel straight OT. All dead end roads leading us to cry out who will deliver us!?

Thanks Sarah. This was a hard one to take. From what I could see, Anthony seemed like a very special dude. Seemed like he was heading in a very hopeful direction, then this. Thanks for what you do in bringing hope and grace to people.

I wonder what medication Bourdain was on. A family member of mine has been suicidal twice in his life; both times he was on a Med later known to cause suicidal thoughts or anxiety: However, the first episode, he was in ministry. So…..

[…] Imagine feeling so controlled and hemmed in by the expectations and demands of the world, and becoming so resentful for not being able to measure up, that disfiguring your own beauty feels like freedom and mercy and the grace of God. Both celebrities have heartbreaking stories, and remind me of one of my favorite Sarah Condon quips: we were not made to be famous. […]