1. First up, Pew released the results of a recent survey on a religious beliefs, glossed this week by The Atlantic:

The third finding reported in the study is by far the most striking. As it turns out, “American ‘nones’ are as religious as—or even more religious than—Christians in several European countries, including France, Germany, and the U.K.”

“That was a surprise,” Neha Sahgal, the lead researcher on the study, told me. “That’s the comparison that’s fascinating to me.” She highlighted the fact that whereas only 23 percent of European Christians say they believe in God with absolute certainty, 27 percent of American nones say this. . . .

So more than a quarter of ‘nones’–those who identify as atheist, agnostic, or otherwise nonreligious–are absolutely certain of the existence of God. Maybe people are more skeptical of religious forms, rites, and theologies than they are of God’s existence. It’s not that there’s no Man Upstairs, just that you have to distrust everything you hear about him.

“I hypothesize that being ‘spiritual’ may be a transitional position between being Christian and being non-religious,” said Linda Woodhead, a professor of politics, philosophy, and religion at Lancaster University in the U.K. “Spirituality provides an opportunity for people to maintain what they like about Christianity without the bits they don’t like.”

There’s an interesting problem here, and it runs deeper than just ‘cafeteria Christianity’. (We’re all cafeteria Christians to some extent–I don’t think half so much about eschatology as I should, nor a quarter as much about angels.) The issue is with the ‘efficacy’ of the beliefs themselves.

As a thought-experiment, suppose I wanted to craft a religion which would make me happy, from a purely blank slate. My first step might be to come up with a perfectly loving God. But dreaming up a God oneself is like paying someone to be your friend. If you know you’ve paid them, the friendship will be a pretty poor salve for loneliness. You feel love from a genuine friendship because you know it’s not made up–the friendship must have an objective existence apart from your machinations. Same with my loving God–if I dream him up, I don’t feel very loved.

Crafting a religion is a self-defeating enterprise. For something to produce good feeling, it must be true (or at least be perceived as true); for something to be true (or perceived as such), it must be received rather than constructed (or perceived as non-constructed). Even Pygmalion, who fell in love with the statute he sculpted, needed Aphrodite’s intervention to bring it to life. That which he constructed couldn’t really come to life without a gift from outside himself.

So the study’s finding that American nones are ‘more’ religious–presumably because more of them are absolutely certain of God’s existence–bears qualification. Faith is a matter not only of the fact of God’s existence (God’s existence being one of the most philosophical, least personal, things about God), but also of what God is like. “Do you believe in total-immersion baptism?”, the old joke goes, with then reply, “Believe in it? I’ve seen it done!”. Existence of something is interesting, but it’s one’s attitude toward and relation to that thing which matter.

2. At Christianity Today, Fleming Rutledge expands on the difference between spirituality and religion, on the one hand, and God’s revelation in Christ, on the other:

I am also using religion in the sense that Karl Barth used it. He calls religion “a human work” and goes on to say that “a religion adequate to revelation and congruent to the righteousness of God … is unattainable by human beings.” This statement—about the incapacity of humans to come up with the story of God in Jesus Christ—is a foundational affirmation of the Bible and essential to the renewal of the church.

Spirituality, too, like religion, is essentially a human activity or trait that stands in stark contrast to faith. To put it in the simplest terms possible, spirituality is all too easily understood as human religious attainment, whereas faith itself is pure gift, without conditions, and nothing can be done from our side to increase it or improve upon it. On the contrary, we throw ourselves upon the mercy of God, saying, “Lord, I believe; help my unbelief!” . . .

These so-called “New Age” philosophies, where “everyone believes everything,” seemed new back in the ’70s and ’80s. But they have since become integrated into the psychological makeup of our contemporary culture, so much so that we hardly notice them anymore: “Master the possibilities.” “Create your own reality.” “Live your truth.” These ideas about human self-creation are deeply religious notions. They are born out of illusion, wishful thinking, and a failure to look radical evil straight in the face. Human potential—which often takes the guise of “spirituality”—has itself become the object of worship.

Not that Christians ourselves can’t also worship human power. Forms of Christianity throughout the centuries have fallen prey to this, turning it into a religion based on moral achievement. To paraphrase Solzhenitsyn, the dividing line separating divine salvation from self-salvation does not run primarily between denominations or time periods; it runs straight through every human heart. Fleming continues:

The message of Jesus Christ, in sum, is this: Salvation is not in your hands. “Do not be afraid, little flock, for your Father has been pleased to give you the kingdom” (Luke 12:32). He is doing for himself great things that we cannot even imagine. Therefore be bold, be unafraid, dear brothers and sisters in the Lord. We have a great gospel. There is nothing else like it in heaven or on earth. It is neither “spiritual” nor “religious.” Rather, it is the still, small voice that you do not expect and cannot command. It is the trumpet call of the age to come. It is “the word of God, which is indeed at work in you who believe” (1 Thess. 2:13).

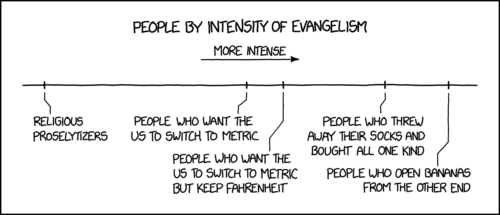

credit: xkcd

3. Over at The Point, Jon Baskin questions the subordination of intellect to political strategy. The essay is refreshingly personal, as he recounts his time working at a partisan think-tank (“once you got the hang of the narratives, everything fit into them”) and his later immersion in more intellectual magazines, like n+1. His essay ruminates on the spectrum from purely political writing to more purely intellectual writing, trying to sketch a vision for how intellectual inquiry and political advocacy should relate to one another.

The entire essay’s worth a read, but the most interesting part to me was his struggle in reconciling his Leftist ideology with his everyday life. Political ideologies, like religions, can have a totalizing element: they purport to explain everything, to relate to “every square inch” (to borrow that sort of tiresome Kuyperian phrase) of human experience. The result is a classically Pauline dilemma: that old tension between belief and action, a sort of friction between one’s personal “is” and “ought” like the scraping of tectonic plates:

We were not merely going to report on progress; we were going to make it.

It was exhilarating to try and live this way. It invested what might seem like trivial everyday decisions with a world-historical import. At least that’s how it felt to me for a little while. Eventually, I began to notice in myself a tension that also existed at the heart of the project of n+1, and of many of the other little magazines. My aesthetic and cultural tastes, the reflection of a lifetime of economic privilege and elite education, did not always, or often, match the direction the magazines were trying to take me politically. This had not troubled me before, because I had never considered that—as the little magazines echoed Fredric Jameson in asserting, or at least implying—“everything is ‘in the last analysis’ political.” But now I had come to see that politics were not just an activity that people engaged in at certain times: when they voted, or protested, or wrote newsletters for think tanks. It was something that could be said to infuse every aspect of one’s experience, from which big-box store you shopped at for your year’s supply of toilet paper, to what restaurants you chose to eat at, to who you chose to sleep with. This was what it meant not just to engage in politics but to “have a politics”—a phrase I probably heard for the first time at that n+1 party, and that was often brandished as if it legitimated one’s entire way of life. What it meant for everything to be in the last analysis political, I came to see, was that everything I did ought to be disciplined by my politics. But what if it wasn’t? Should I then revise my politics, or myself?

Christians of unusually active conscience will recognize this quagmire immediately. Do I revise my religion, or myself? And Christianity purports to be explicitly a religion of forgiveness. If the self-judgment is that bad for a religion of grace, how much worse for belief-systems which merely stop at describing right and wrong?

Transcendent thought-systems elevate us, pronouncing our every act a moral act, filling all around us with saturated meaning. Yet the ideological system is impersonal; the tenets themselves cannot give us the power to act in accordance with them. (The irony is that according to an ideological system–at least, according to most such ideological systems–action is the thing which matters.) Sometimes, one gets the sense that the current profusion of ideological essays is less geared to intellectual development and more geared to supplying moral motivation–that missing impetus which will finally give us the strength to live in accordance with the system’s demands (you certainly get that sense in the Religion section of the bookshop). What the system lacks is an explanation of the human heart, and why it often fails to do that which we ask of it. No matter the system, the person caught between “is” and “ought” winds up with the question–“Who will rescue me []?” (Rm. 7:24).

4. A wonderful illustration of love–love of the ‘incarnational’ variety–showed up this week at Colorado Public Radio, which reported on a man who went to live for a week on the streets with his homeless, drug-addicted son:

Frank was working in his garden when the idea came to him. He ran in to tell his wife the plan: travel to Denver, find their son and live with him on the streets for a week.

“She looks at me like I’m nuts. And honestly maybe I am. But I love my son. And if I’m honest, I think his days are numbered,” Frank writes in his essay . . .

Frank’s essay will be read live on June 5 by a Jerry Herships, a pastor involved in homeless outreach, and we’ll be tuning in.

Herships hopes sharing Frank and his son’s story will encourage the public to humanize homeless people they may encounter.

“There’s a real sense of ‘those people are the other.’ And until we get to know their name and know what they look like when we look them in the eye, until we actually form a relationship, they can pretty safely be the other,” Herships said.

Conner hadn’t seen anything like Frank’s experience in more than a decade of work, let alone one so well documented. More than a story about homelessness and addiction, Conner found himself relating to the essay as an account of fatherhood. At one point Frank says something to his child that Conner could hear himself repeating to his son as he drops him off at daycare.

“I’ll be with you, every minute of the day,” which became the title of the essay and the live reading.

5. In culture, Joshua Rothman at The New Yorker considers the transformation of Star Wars from a story to more of a cinematic universe, where the stories take a backseat to a sort of endless, almost procedural generation of narratives:

We’ll keep up with the new movies not because we want to find out what happens—the plot, if one exists, will be an impenetrable trellis of intersecting arclets—but because we like their vibe, their look, and their general moral attitude.

(An impenetrable trellis of intersecting arclets!) I think Rothman’s critique misses the fact that Star Wars has been a sort of “cinematic universe” long before Disney purchased it. Does anyone else remember Caravan of Courage: An Ewok Adventure? (If not, that could be for the best.) But I think he’s onto something with the attachment to vibe, look, and general moral attitude. It becomes almost more of a genre-sell than a story. Still, I really liked Solo, despite sort of not wanting to, and think it’s a good movie–once you get past the genre stuff.

Also in culture, the NYT published a decent article on Dostoevsky and modern crime stories, drawing the moral that

As Dostoyevsky implored through his novels and reporting, it is not only our task to support the innocent or wrongly convicted but also to recognize the humanity of the guilty and the shared sense of responsibility that we have for one another.

And in the probably-deserves-a-post-of-its-own category, the June issue of The Atlantic describes American meritocracy as a new aristocracy. Turns out that as our society becomes more purely based on earning one’s status and money, it hasn’t necessarily gotten more merciful. Also turns out that meritocratic elites can give their children a significant leg up, and that meritocratic elites don’t always recognize their privilege. Again, possibly more to come, if someone decides to write this one up.

Strays: The Atlantic wrote up an article on the idea of a midlife crisis, adopting a sort of understated skepticism about it. For those interested in theology, John Barclay’s Firth lectures are up, and I hear they’re brilliant, especially the first. That’s it for this week–happy weekends to all.

COMMENTS

2 responses to “Another Week Ends: Theistic ‘Nones’, Fleming on Faith, Ideological Is-es and Oughts, Urban Kenosis, and the New Meritocratic Aristocracy”

Leave a Reply

Thx, Will

Wonderful, jam-packed weekender as always, W. Love the thought experiment, and that story about the father with his homeless son – woah. Plus, the Baskin quote! The cup runneth over.