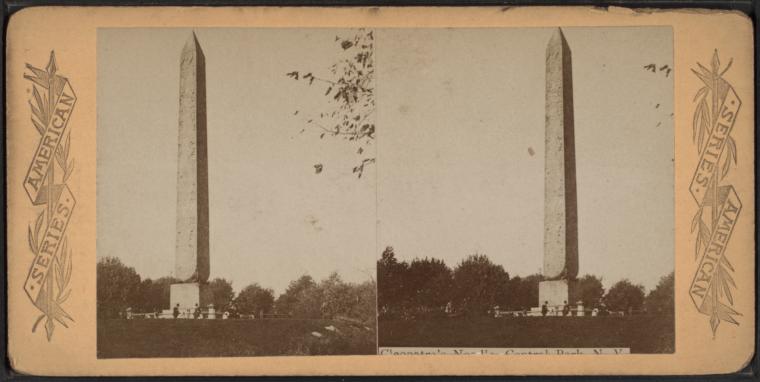

For about a century, proud and dead Americans imagined themselves to be Egyptians. Throwing away the simple, hopeful crosses of common grave-marking, and setting aside the robust traditions of soaring angels and death’s heads of Puritan or German decoration, we erected obelisks in our own memory. It doesn’t seem to have ever extended to mummification and canopic jars, but it was a fad of fads that grew up following the Napoleonic spoliation of Egypt—and the sudden appearance of Cleopatra’s needles in Paris, Rome, London, and New York. It ended as abruptly as it began. But the obelisks still poke the firmament from among their Victorian neighbors: the marble lambs sleeping on green grass, the funerary urns, the mourning drapes, the turtledoves.

Some of my family were faddish enough that there are Howell, Roseberry, and Rial obelisks to be found among the necropolises of Pennsylvania. Whenever I find one, I ask myself why. You were Lutherans, you were German Reformed, you were Episcopalians, you were Methodists betimes. Why the obelisks? (I shun Dr. Freud except when I don’t, and when I have visited the Washington Monument.) Unless we imagine an American Egyptianism as a corollary to British Israelitism—and this can be done—it was nonsense for American Christians to set up obelisks for themselves. And there is no end of joy for me that I have, among my kin, a person who once kicked this stupid trend with laughter.

My sixth great-grandfather David Wagener (1736-1796) laughed at the Egyptian American way of death, and at death itself, by putting a top hat on his obelisk. I love him for it, and I have visited his grave a few times each decade since I was a child—first with a grandmother who regaled me with stories about him, and this week with the daughters, who are the brightest green leaves of a tree the good dead man planted here on America’s shores. He was a farmer and a judge, a distiller and a miller, the beginning with his wife Susanna of a dynasty that would never call itself a dynasty. It is now the case that there is no person living who ever met a person who knew a person who had heard his voice, and yet he causes laughter down the corridor of the ages. From the grave, he is an evangelist of laughing and of boldness.

David came honestly by his death-sleep, and by the laughter. He was born in a Schwenkfelder community in far, far eastern Saxony, and arrived in Philadelphia in his widow-mother’s arms as a suckling refugee thirteen-month-old. His father Caspar had died—likely by his own hand after years-long Jesuit interrogation and intimidation—before the boy was born. David’s uncles Melchior and Balthasar fill out our family roster of the Magi, but David is a man who made himself in young America without gold, frankincense or myrrh to start, yet all of them in spades to end. I would have liked to have known him, and sometimes I think I may someday.

For two thousand years, Christians have laughed at death: its sting, its victory, its power, its three-day prison. We have also been uncertain about how to approach the cultures around us and among us who erect stelae to crown the honor a person has earned during life. Despite being followers of a man who left his own tomb rather swiftly, we have built and continue to build shrines to ourselves that do not invite a visiting mourner to pray in thanksgiving for souls at rest; nor do they invite us to reflect on our own mortality; nor do they offer a tangible comfort other than what God can–and does–speak to the human heart in the stillness that may arise in a cemetery. The American obelisks are a particularly horrible episode of this failed cultural negotiation.

David’s game on this wise is unusually strong, because he puts a permanent, defiant No on the sky-piercing attempts of the Egyptian needles. He saw, perhaps, that in their pharaonic oddness they needed someone who would engage with their narrative and just stick a hat on it. And it was not an Egyptian hat, but his own hat.

Easter tells us in the simplest of terms that death is dead, and it invites us to make our grave-song an Alleluia. My David cracks a joke in stone to say the same.

COMMENTS

One response to “Top Hat Meets Obelisk”

Leave a Reply

Very good. It is sure hard for us to get over ourselves, isn’t it?

PS. Can you add a photo of the top hat?