There are already scores of recaps of Game of Thrones season finale readily available online (see this fine one from NPR for starters). I feel no compulsion to add to the already abundant list. But there was something that stuck out to me that is worth a little reflection. It’s something that has characterized the entirety of the series but of late, for me at least, has become more pronounced. The genre of Game of Thrones is of course fantasy, and like most fantasy stories it’s set in a premodern world. The technology, culture, and religion all seem pre-modern through and through. Despite this fact, the existential trouble that besets most of the main characters is decidedly late modern in nature.

In The Courage To Be, Paul Tillich describes three sources of anxiety: fate and death (the anxiety of death), emptiness and loss of meaning (the anxiety of meaninglessness), and guilt and condemnation (anxiety of condemnation). These forms of root anxiety are not mutually exclusive, and the presence of one doesn’t negate the presence of others. During the Patristic era, when the Church was taking shape, the dominant form of root anxiety concerned death and non-being. Theologies of the cross were not as prevalent as theological reflection on the miracle of the Incarnation and the power of the empty tomb. As late antiquity gave way to the Medieval period, the anxiety that came to the forefront was that of guilt and condemnation. In response to this shift, theologians like Anselm began to mine the theological riches of Christ’s substitutionary work. But modern people are not tyrannized as much by guilt and the fear of condemnation but rather, according to Tillich, the anxiety of emptiness and loss of meaning. Nihilism becomes the primary thorn in the flesh of the modern soul.

Tillich doesn’t think that a reassertion of premodern dogmatic certitude will rectify the modern predicament. Tillich claims that “[t]here is only one possible answer, if one does not try to escape the question: namely that the acceptance of despair is in itself faith and on the boundary line of the courage to be. In this situation the meaning of life is reduced to despair about the meaning of life. But as long as this despair is an act of life it is positive in its negativity.” The kind of faith that “makes the courage of despair possible is the acceptance of the power of being, even in the grip of non-being… Even in the despair about meaning being affirms itself through us. The act of accepting meaninglessness is in itself a meaningful act… It is an act of faith.”

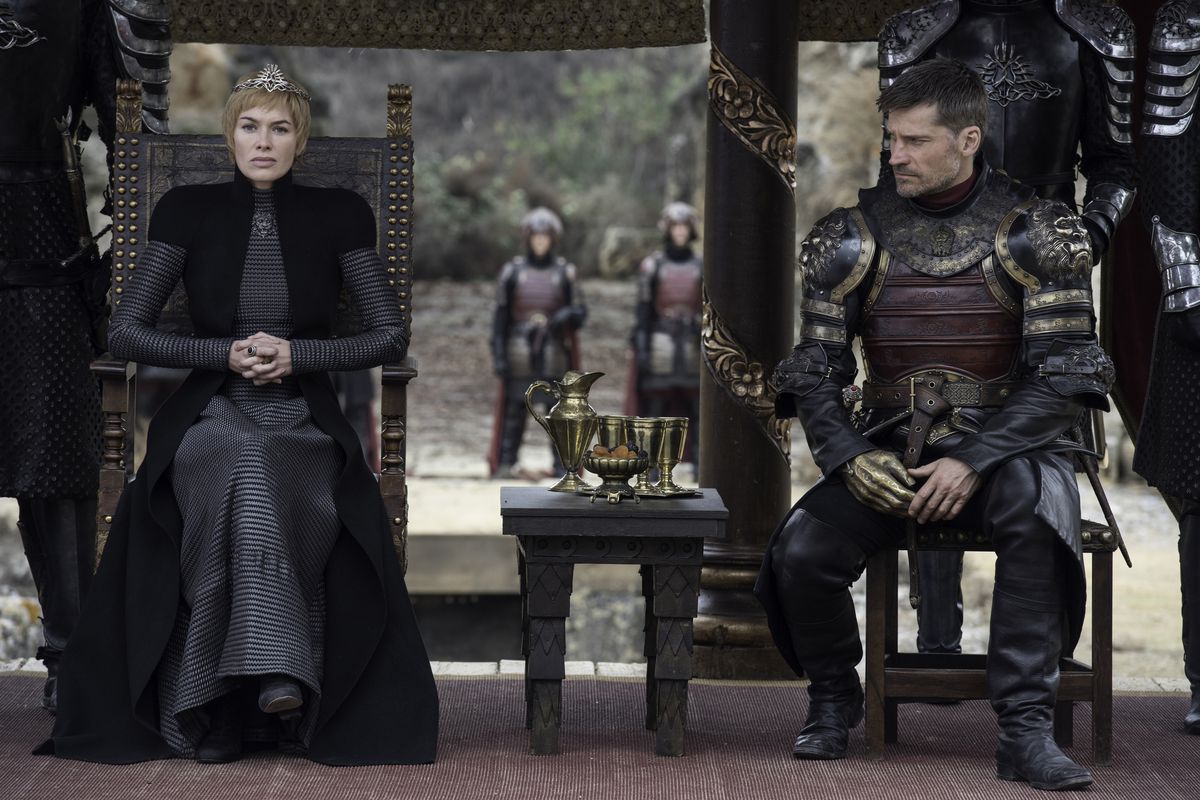

In the season finale of Game of Thrones, when the seemingly insane plan to bring a member of the Night King’s army actually seems to work (it also inspired this great video likening the band going north to capture one of the undead to the A-Team), Cersei gives voice (with perhaps mixed sincerity) to the anxiety that the impending zombie army generates. It’s not primarily the fear of death. Everyone of the main characters, even Jon Snow, has a sense of their own mortality. Rather, it’s the fear that if the Night King prevails, the world as they know it will be over. No more houses, no more legacies, no more Iron Throne or games to possess it. Everything all of the characters have done will be rendered meaningless. The thin lair of cynicism that often exists in most of the main characters gives way to the revelation that there exists something that might make everything they know and everything they’ve done pointless.

The esteemed sociologist Peter Berger pointed out that in premodern society, it took real courage to be a heretic, whereas in late modern life there exists a kind of heretical imperative. Everyone is forced into a place where they must exercise “radical choice”. Less and less is dictated by necessity. One’s core convictions must be discovered, questioned and always re-evaluated. The problem is that you want to be able to see through some things, through the lens of critical inquiry, but what if it leads to seeing through everything? As C.S. Lewis pointed out, you want to see through the window but not through the rosebush outside in the yard. To see through everything is to ultimately see nothing at all. Many of the fictional friends we’ve become attached to in the world of Westeros are probably so compelling because, despite their premodern setting, they seem to feel much of the sting of our late modern predicament. They have premodern bodies with late modern souls.

Premodern religion doesn’t speak well to the late modern dilemma. Nor do the religions of Westeros. Not that there aren’t pious devotees in Game of Thrones. But the few significant characters that are devout (for instance, the Sparrows or some of the disciples of the Lord of Light) seem to find in their religiosity a resource to suppress their anxiety about meaninglessness, rather than having faith as a resources to address it.

Both the religious and the irreligious are required to exercise what theologian Brian Gerrish calls “elemental faith” to negotiate modern life. But this faith is often not considered very religious or oftentimes isn’t understood as faith at all:

There is, however, one kind of faith that is justified not by demonstration but by the recognition that we cannot do without it. I mean the elemental faith that underlies all human activity: confidence in the intelligibility of the world we experience and of our own existence in it. We encounter our environment as order, not (impossibly!) as chaos. Without this confidence, not only religion but also the entire enterprise of science and learning and, quite simply, living and being human would collapse. As a rule, it is tacitly presupposed rather than explicitly affirmed; and many of those who do affirm it might not wish to acknowledge its status as faith. In its very essence it is a confidence that can only be exhibited or elicited, not proved; and it has the further characteristic that its validity cannot be disproved either, since every argument against it presupposes what it intends to disprove—the rational structure of experience. The correlate of this elemental faith is the order, meaning, or reasonableness—in short, the logos—that the experienced world actually has, and the Christian theologian will add that there we have the elemental concept of God. But elemental faith, so understood, is not peculiarly Christian, or even peculiarly religious. Much less is it contrary to reason. It is the faith on which the exercise of reason, tacitly or explicitly, always rests. And its opposite is neither unbelief nor heresy, but the despair of nihilism and meaninglessness.

Most premodern people were not confronted with the possibility of extinction-level events. But the Night King’s army functions for the main players in Game of Thrones much the same way that Ernst Becker thinks the awareness of the sun’s eventually cooling and the subsequent end of our reality as we know it does for us. This causes not just anxiety about death but anxiety caused by the death of meaning.

Gerrish sees the Christian faith as a religion where “elemental faith is confirmed, specified, and represented as filial trust in God ‘the Father of Jesus Christ…’” He thinks that 500 years after the Reformation, the modern person is not afflicted primarily by a troubled religious conscience like that of Martin Luther:

To what then, shall we conclude, is the gospel addressed? The traditional Protestant answer has always been that the Christian proclamation speaks to human sin and guilt, so that where guilt is not present it must be induced: the bad news of the law must precede the good news of the gospel. The forensic language of justification—of condemnation or acquittal by the divine Judge—lends itself to such an ordo salutis, but it is more context-bound than Protestant evangelists have been ready to admit. A message of guilt and pardon suited the Reformation struggle with the terrified conscience, and I do not doubt that it will always have its place in “the gospel of the glory and grace of God.”

But in all I have said about elemental faith, estrangement, and the work of Christ I have opened the possibility of identifying another point of contact that lies deeper and may come to expression in more ways than one: the loss of confidence in a reliable environment, a coherent world order in which it makes sense to ask for the meaning of our existence—our place in the whole. I have argued that this confidence has the logical status of an “inevitable belief,” not open to proof but tacitly presupposed by our theology, our science, and— quite simply— our daily existence as human beings; in this lies its rational justification… In everyday experience, however, an appeal to rational justification cannot be counted on to ward off the intrusion of the sense of emptiness or meaninglessness that theologians, philosophers, and psychologists have identified as a characteristic sickness of our time. But the gospel is addressed precisely to the predicament of elemental faith under siege: it comes with the reassurance that this faith is not, after all, a delusion. Reconciliation with God “the Father of Jesus Christ” is restoration of the elemental trust that estrangement erodes.

Gerrish is persuasive here, and some have noted that the place of primary theological reflection for our time should not be Bethlehem or Golgotha but Galilee where we meet Jesus the prophet and teacher who can speak meaning into the deep, abiding sense of meaningless that pervades so much of modern life. There’s much food for thought there. But as Robert Capon points out, there seems to be a shift in the main thrust of Jesus’ parables after the death of John the Baptist. The parables of the Kingdom give way to what Capon calls the parables of grace, parables that largely tell a story of death and resurrection:

True enough, the early kingdom parables (especially those that employ the imagery of seed being put into the ground) are not incapable of being given a death-resurrection interpretation; but in telling them, Jesus does not yet seem to be talking about his own dying and rising. These early parables focus chiefly on the paradoxical characteristics of the kingdom; they portray it as catholic rather than parochial, actually present rather than coming at some future date, hidden den and mysterious rather than visible and plausible; and they set forth the bizarre notion that the responses the kingdom calls for in the midst of a hostile world can vary from total involvement to doing nothing at all.

But these first parables do not, in any developed way, enunciate the paradoxical program by which the kingdom is in fact accomplished, that is, by death and resurrection… The development of that theme comes, as I see it, only in the parables of grace—and it comes after a series of events and utterances (Aland nos. 144-164) that show Jesus more and more preoccupied with death. Beginning with the death of John the Baptist (Matt. 14, Mark 6; cf. Luke 3), and continuing through the feeding of the five thousand (Matt. 14, Mark 6, Luke 9, John 6), the first prediction of his death and resurrection (Matt. 16, Mark 8, Luke 9), the transfiguration (Matt. 17, Mark 9, Luke 9), and the second prediction of his death and resurrection (Matt. 17, Mark 9, Luke 9), he gradually reaches a clear realization that the working of the kingdom is mysteriously but inseparably bound up with what Luke (9:31) calls his “exodus”—in other words, with the passion and exaltation that he is shortly to accomplish in Jerusalem.

At the heart of the teaching of Jesus, we find a theology of the cross before he gets anywhere near his own crucifixion. The key to the meaning of life, says Jesus the Teacher, is that when you’re not trying to save your life, you stop losing it. It’s leaning into the fragility and finitude that faith invites, and with it true freedom. This is nowhere better summarized than in the words of Frank Lake:

While we regard our humanity as a container which ought to have something good in it when we look inside, we miss the whole point of the paradox. We are not meant to be self-contained, but channels of the life and energies of God Himself. From this point of view our wisdom is to let the bottom be knocked out of our humanity, which will ruin it as a container at the same time it turns it into a satisfactory channel.

These are words of deep wisdom for late modern souls, whether they inhabit the world of Westeros or our own.

COMMENTS

8 responses to “Faith of Thrones”

Leave a Reply

Really appreciate this Scott. As an avid GoT fan (especially this season) I can’t help but notice that “Death is the Enemy” has been recurring refrain.

In fact, with the death of a key “semi-evil” character (most recently) there really isn’t much more than one “human” villain left on GoT (which in itself is shocking). The antagonists have indeed become in order (1) Death and (2) Those who think they can be like God….it really is an alarmingly profound low anthropology pitted against both death,AND glory theologians. I think that’s what is making me dig it so much right now.

From the second the episode started, I was looking forward to the inevitable Mbird post on it. Thank you, Scott!

In Cersei Lannister we have a character shrouded in death. Over her life she has buried both parents, all three children, a husband (whom she detested anyway), and at least one cousin (Lancel) and uncle (Kevan). She’s toppled both populist (Tyrell) and insurgent (Martell) families; overturned the seat of religious authority (with the Sept) and all its adherents (Sparrows). She is flanked at the dragon pit by her undead bodyguard and the scientist who helped her accomplish this “resurrection.” No wonder she’s been wrapped in black all season: perpetual mourning and death.

I think you’re dead right, that it’s ultimately the meaninglessness that the wights represent that finally seems to move her and everyone else. Though still her pride continues to go before destruction and before her inevitable (?) fall.

This is super on every level. thank you Scott. Just ordered The Courage To Be.

One of the best Mbird reflections. While I do enjoy GoT, it’s use here is more a solid stepping stone to Tillich and Capon and honesty about who and how we are. I appreciate that there is thoughtful theological/psychological nuance here, and not simple an “easy” fall back to the law/gospel diad. I’m really grateful.

Love this Scott! A few more thoughts on this season of GoT that I don’t have time to put in a post.

1. Can we talk about Jon Snow’s forgiveness of Theon? Related to this post, in light of the great, overarching apocalypse approaching from the North, it does seem that reconciliation is more prone to happen when one’s own mortality is embraced. Also, that a forgiven Theon is able to defeat his attacker through the result of his, erhm, unique suffering at the result of Ramsey Bolton?

2. I thought Littlefinger’s death was a little contrived. I think it goes back to Will’s observation that GoT has played out in a place between the story we want to see, justice, goodness, and kindness emerging victorious, and the reality of life, that those virtues can also be liabilities in the great game. It’s almost as if Littlefinger existed, and the plot is going apocalyptic, and the writers said “wait, how are we going to end Littlefinger’s storyline?” Would it have been more interesting to have Littlefinger emerge alive and helpful in the final battle despite his conniving, like he did at the Battle of the Bastards? Part of me thinks so, or at least it would have been more true to life. Sansa’s concluding comment, “I think he did love he, in his own, twisted way,” was a story that could’ve been told even more.

OK, all done.

Bryan,

With regard to Littlefinger and the contrived feel of it, see this Atlantic piece: https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/08/bran-stark-and-the-problem-of-omniscience/538347/.

Yes! I appreciated that Atlantic article. I think it gets to my itch that Littlefinger’s death could have had a lot more drama to it.

Thanks for all the kind words!