I had the honor of presenting earlier this week at “The Art of Failure” event here in Charlottesville, alongside Invisbilia co-host Lulu Miller and musician Devon Sproule. You can listen to all of the recordings on the Christ Church site, but here’s the modified/edited transcript, the first portion of which is adapted from A Mess of Help. Sincerest thanks to New City Arts and The Garage for co-sponsoring! What a fabulous evening.

In 1966, The Walker Brothers reportedly had a bigger fan club in the UK than The Beatles. Boggles the mind but it’s the truth, or close to it. The three sullen young Californians–not actually brothers, only one named Walker–were a rare instance of a reverse British Invasion: teen idols across the pond who hardly made a splash in their native country.

The wave crashed in 1968, when lead singer Scott Walker (née Engel) decided to go it alone, releasing a succession of solo albums, the cleverly titled Scott 1, Scott 2, Scott 3 & Scott 4. The first couple were split between heavily orchestrated, highly literary ballads penned by Scott and heavily orchestrated, highly literary translations of Jaques Brel tunes (with the occasional Tim Hardin cover thrown in for good measure). It’s safe to say they’re an acquired taste.

Scott 3 slowed the tempo down and upped the impenetrability quotient even further–with the notable reprieve of the acoustic “30th Century Man”, which some will recognize from The Life Aquatic. Whatever teenyboppers were still paying attention got off the train after Scott 3. So much so that when the considerably more commercial Scott 4 appeared in 1969, it stiffed. Maybe fans were put off by the (amazing if admittedly pretentious) Camus quote on the back, or the Bergman and Stalin references in the tracklist, who knows. If they had only listened, they would’ve discovered a masterpiece, packed with humor and melody and—gasp—drums! Scott had clearly poured everything he had into the recording, writing all the songs, taking great care with the arrangements and overall cohesion. You could argue that Scott 4 invented twee.

When Scott 4 tanked, the perceived judgment was devastating, and Scott retreated into what by all accounts was a pretty serious drinking habit. In his depression, the record label somehow convinced him to spend the next five years recording easy-listening standards aimed at the nostalgia crowd, none of which went anywhere either. To fans of Scott 1-4, it felt like a betrayal; the artist, for all intents and purposes, had been killed.

When Scott 4 tanked, the perceived judgment was devastating, and Scott retreated into what by all accounts was a pretty serious drinking habit. In his depression, the record label somehow convinced him to spend the next five years recording easy-listening standards aimed at the nostalgia crowd, none of which went anywhere either. To fans of Scott 1-4, it felt like a betrayal; the artist, for all intents and purposes, had been killed.

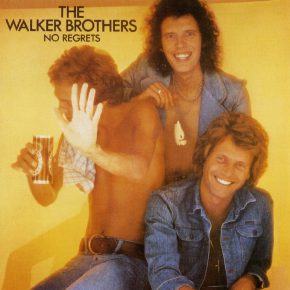

Yet the story goes on. With spirits and economic prospects flagging, The Walker Brothers reformed in 1975, and against all odds, scored a Top 20 hit with a charming if safe version of Tom Rush’s “No Regrets”. However, one look at the sleeve of their first reunion record tells you all you need to know: in lieu of autumnal Parisian self-seriousness we’re confronted with bright colors, shirtless beer-swilling, Tennessee tuxedos and white-boy afros. The follow-up failed to capitalize on the modest momentum, and it soon appeared as though the group’s second coming had stalled out.

Which is where things get interesting again. Their record company was going out of business, so for the third reunion record, the guys were given free rein to do whatever they wanted, independent of any commercial concerns. The lack of pressure or oversight of any kind—i.e., freedom—had a resurrecting effect on Scott, who decided that the album, Nite Flights, would consist entirely their of their own compositions, the opening four of which would be the first Scott originals in eight years. Sonic inspiration arrived via his most famous disciple, David Bowie, who had recently embarked on his Berlin trilogy with producer Brian Eno (Low, Heroes). For the cover image, the Walker’s did an aesthetic 180 and went full noir:

The songs were not only a return to form for Scott, they represented a new vanguard for popular music, period; menacing keyboards, intentionally muddled vocals, disco bass work, stabbing guitar lines, and fragmented lyrics, the first side of Nite Flights was a whole new energy. I read somewhere that Radiohead initially formed over their mutual admiration for the record. (The good people of Portishead owe their entire career to the song “The Electrician”.) After listening to Nite Flights for the first time Bowie apparently commented, “I see God in the window.” Brian Eno lamented that it had only taken Scott four tracks to eclipse their Berlin efforts. “We still haven’t gotten any further,” he opined in 2006.

Of course, the record didn’t sell anything, and the Walkers were out of a company and a contract. Scott, however, was reborn. And he’s never looked back. You can read about the rest of Scott’s brilliant, eccentric journey in A Mess of Help.

I relate the story because of what it tells us about failure. It took a while, but the flop of Scott 4 and the reunion records introduced Scott to life on the other side of Should. Meaning, commercial failure freed him from the shackles of needing to achieve a certain (measurable) outcome or response with his art. It cast shade on the almighty failure-success axis.

We’re all familiar with the Should. Sometimes it’s external (sales projections, etc), but more often it’s internal(ized): the voices of critics, bosses, nemeses, parents, interlocuters, even your past self, you name it, telling you that your work must be original, transcendent, good. Or, if you’re a writer, it must be insightful, fresh, compelling. Or else:

These are all outcome-based modes of thinking, what we would call “law”, and anathema to the creative mind—in the long term at least. Anne Lamott puts it this way Bird by Bird:

What I’ve learned to do when I sit down to work on a shitty first draft is to quiet the voices in my head. First there’s the vinegar-lipped Reader Lady, who says primly, “Well, that’s not very interesting, is it?” And there’s the emaciated German male who writes these Orwellian memos detailing your thought crimes. And there are your parents, agonizing over your lack of loyalty and discretion; and there’s William Burroughs, dozing off or shooting up because he finds you as bold and articulate as a houseplant; and so on. Quieting these voices is at least half the battle I fight daily.

Failure has a way of momentarily quieting these voices–a negative verdict forces a confrontation with the glaring discrepancy between “should” and “is”. Failure reframes the questions the artist asks themselves. Instead of what should I create or who should I be, you ask what am I creating? Who am I? If I can’t say what I should say effectively, what do I want to say? These, by the way, are the more difficult questions—and ones which never receive a complete answer. Which is why they’re also more fructifying.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7kf3Hyxl67g

If it sounds abstract, I speak from personal experience. The first few years of Mockingbird bore this out, for example. We had been given an opportunity in New York and knew we wanted to do something creative. Yet those initial years, at least for me personally, were spent listening to the voices about what it “needed” to be: who we should reach and the kind of approach we should adopt in doing so. I knew what this person thought, and that person. I knew what the people with the deep pockets thought. I wasn’t sure–or wasn’t confident–about what I thought.

Needless to say, that kind of thing is draining and unsustainable. Absent a clear sense of direction, the should’s compete in a death-match in which everyone gets hurt. After three years of breathing in that air, the project got to the point where it felt like it had run its course. Financial stress combined with perceived disinterest and interpersonal conflict to foster exhaustion. We’d given it a shot–no regrets, ha!–but the boulder wouldn’t roll any further. At least, I was tired of pushing.

I remember telling my wife that we had about four months left in the bank, maybe five if we scrimped and saved. So while we looked for the next step to materialize, we resolved to spend the rest of the money doing what we’d been wanting to do all along. We take some risks and make our “final” conference one to remember. Which, of course, is when the whole thing became fun again. Also when it started to take root and become what it is today.

A culture that worships venerates productivity takes stories like these and turns them into a formula. Business gurus redraw map to success with a few more valleys. Silicon Valley itself misappropriates Samuel Beckett and urges us to Fail Harder. That’s the way to get where you want to go.

It’s not that these new contours are descriptively inaccurate—they aren’t!–it’s that the moment they become prescriptive they cease to apply. Because failure on the way to success is not actually failure at all. It’s another Should masquerading as relief. Extolling failure as a more potent means to success is a subtle method of avoiding it altogether.

Real failure happens to a person. It hurts. It is painful. It feels final and out of one’s control. And there’s nothing we like less than that. When it came to Mockingbird, I may have known in my head that relinquishment was the only hope of survival, but I couldn’t will myself to let go. In fact, I kicked and screamed against that eventuality with every ounce of my being.

So failure is not a strategy. The second you try to make it one, it is no longer failure.

But that doesn’t mean it cannot teach us things. You can learn things from failure that you cannot learn elsewhere. And that’s what it’s been—and continues to be—for me: a teacher. Three lessons that spring to mind would be:

1. Our conception of what constitutes failure and success is by definition narrow, arbitrary and often self-defeating. Furthermore, there are different kinds of success and failure, almost as many as there are people.

I’ve told the story elsewhere, but I can’t help thinking about the (second) conference we hosted in Pensacola, FL back in 2010. We had planned for 200 people to register but only 24 could be bothered. It was super embarrassing, and we almost cancelled ahead of time. My wife had just had a baby, so I wasn’t even there. It had been planned during the phase described above, i.e. just as we were throwing in the towel on the whole shebang. So it felt at worst like something we had to get over with, at best like a chance to put some precious content down on tape before it was too late.

Here’s what happened: one of the people in attendance ended up coming on our staff, editing our devotional, and starting our quarterly magazine. You may know him as Ethan Richardson. Another person—ahem, Mark Babikow–decided they wanted to volunteer to do all of our video work (and still do, to this day). Another presenter was inspired to write a book about his presentation that went on to be our best-selling publication, Grace in Addiction. Another attendee ended up as my brother-in-law. Another became one of our most generous and faithful financial supporters. I could go on.

Suffice it to say, my barometer of success and failure proved to be extremely faulty. I had no idea about what was really happening. I still don’t. And neither do you. Which is good news for those who feel like life is a parade of misfires.

Of course, experiences like the one in Pensacola are rare. There are plenty of failures that never take on a different light. They are simply failures, and they don’t teach us anything except what embarrassment or disappointment feels like. We learn that not everything has to have a purpose, and that’s okay. Which is a lesson in itself and one that never gets old. I’m talking about humility (what Flannery O’Connor calls “the first fruit of self-knowledge”) and it’s not something you can be lectured into. Failure has a knack for cutting through fantasy and introducing you to yourself.

2. Secondly, failure teaches us that connection comes at the place of weakness not strength. That perfection(ism) is the friend of paralysis and enemy of creativity. The mistakes in a work of art are not flaws so much as footholds for identification and sympathy. Just watch Patti Smith’s performance from the Nobel Prize ceremony (below) and tell me if her stumbling doesn’t make the moment that much more powerful. Allen Ginsburg captured this truth masterfully in his poem “Ode to Failure”, a favorite stanza being:

O Failure I chant your terrifying name, accept me your 54 years old

Prophet

epicking Eternal Flop! I join your Pantheon of mortal bards, &

hasten this ode with high blood pressure

rushing to the top of my skull as I if I wouldn’t last another

minute, like the Dying Gaul! to

You, Lord of blind Monet, deaf Beethoven, armless Venus de Milo,

headless Winged Victory!

Every work of art he mentions is one that’s been elevated, even immortalized, by its shortcoming.

3. Finally, failure forces some distance between person and project. This is perhaps the most urgent lesson for those of us who’ve grown up in a culture (and species) that makes very little distinction between individual and output, worthiness and resume. We attach ourselves to our creations with such toxic ferocity that when something we do fails, we fail. More than that, we become failures.

Yet those who’ve fallen on their faces find out that the experience isn’t the be-all-end-all personal referendum you thought it would be. Life goes on. Love persists, often coming alive in such moments.

Success, by the way, does the opposite. It adds pressure rather than relieve it. You feel like you have to top yourself. Just ask Axl Rose or Michael Jackson, may he rest in peace.

In prepping for this talk, I realized that my creative process—to the extent that it’s, er, successful–is the process of decoupling myself from outcomes, or outcome-based thinking, AKA fear. “Flow state” is simply what happens when the content of what’s being created or written about overtakes trepidation about the response, and what that might say about me. It is the process of dis-identifying, caring and not caring (Eliot).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qo0STYcoyjM

I didn’t know it at the time, butan experience in high school helped me tremendously in this regard. As a sophomore, my classmates and I were divided into regular English and “honors” English classes. For whatever reason I was placed in the regular section, my roommate in honors. At the end of the year, I approached my teacher and asked her to consider moving me up honors. I had done decently well and thought I could hack it. Looking back, I’m kind of surprised, as I was a pretty retreating teenager.

Her response was a polite, “That’s nice but you are right where you should be.” It probably sounds more crushing than it was. She was a good teacher, and I respected her opinion. I took the verdict to heart only in the sense that writing wasn’t going to be “my thing”. It wasn’t going to be something I consciously pursued. That is, it wasn’t going to be an identity.

This meant that in college, and afterward, when I found that I enjoyed the process of putting pen to paper and seeing what happened, I never took it all that seriously. I wasn’t a “writer”, I was just writing. The lower stakes allowed me to approach the craft more playfully. I didn’t invest the act with overdue emotional/existential weight. It didn’t carry (much) my self-justification–probably a big part of why I kept doing it. Which, it turns out, is the single most reliable way to get better. Go figure.

The process of dis-indentification will be different for everyone. For me, one of the more effective ways I’ve found to shortcircuit creative resistance (i.e. outcome-based paralysis) is a neuroticized version of the distributive property. To keep moving at such a pace that the response doesn’t have the space to sink in. Or if it does, the next creative opportunity is right around the corner. This spreads the existential weight thin enough to approach another day.

If my circumstances had been different I often wonder if any of this would’ve happened. Meaning, as much as the Internet has done to demean discourse (creative and otherwise), this is one area in which it has helped. The time pressure it exacts is not contrived. It is oppressively real, in my case offset just enough by the content, i.e. a message of mercy. There are other ways I’ve learned to hotwire creativity, but they’re less interesting (crowded spaces, etc).

Of course, none of these lessons have ever stuck in a definitive way. You learn them over and over again. Thankfully, there’s no end to failure, other than, you know, the final failure of your body.

And death is where I’d like to end. When I was approached to speak, I was asked if having small children is that the death of creativity. It’s a legitimate question, but the answer is no. There are logistical challenges, sure, but metaphysical advantages too. You think a little less about yourself. There’s a little less time for daydreaming, yes, but there’s also a little less time for second-guessing. Plus, you have a great excuse if something turns out badly. “The kids!” Sort of a creative get-out-of-jail-free card. Certainly you are exposed to different sorts of art, some of which is schlocky, but some of which is great. In fact, sometimes a kids’ movie will inspire you because you’re not expecting it to. You can get blind-sided in the best possible way.

The other night, for example, my kids insisted that I watch Hollywood’s latest anthropomorphic spectacle with them, Sing. They’d seen it in the theaters twice, both of which I’d somehow managed to dodge. But I knew Jason had really appreciated it, so I acquiesced to the steep rental fee. I’m glad I did.

As I sat there, I was overwhelmed by a parable of creativity, par excellance. [Spoiler alert].

The curtain opens on an ensemble of zany characters, all stuck in some kind of crisis and all stifled in their creativity. Into their respective madness blows (literally) an opportunity they can’t turn down: a singing contest with $100,000 prize money. They don’t seek it out. We watch as they all work hard, clear a few obstacles, introduce a few new ones, hone their craft, and nurse their hopes. The Yes of the initial audition activates heretofore unseen gifts, yet it also pits them against one another. How will this underdog story end, we wonder? Who will live happily ever after? No one, it turns out. And everyone.

Their ascendance is short-lived. Just when you think our motley crew of protagonists has pulled off their own redemption (and saved their theater, a la The Muppets), an act of desperate ingenuity—engineered to gain the approval of the loftiest of Judges (Nana Noodleman)—wipes out the entire project. The theater where they’ve been rehearsing is destroyed, and their hopes along with it. The spiritual architecture of the whole enterprise comes crashing down.

And yet… what looks like total disaster proves to be something else. With the stakes removed and the edifice of personal glory dismantled, all that’s left is the act of singing itself. There’s no winning, no losing, no reward, no threat bound up with the outcome. In the place of jitters/fear, perched amidst the rubble of their dreams, we watch as each one of the participants lets it all hang out and sings with pure abandon. What was a competition transforms into a joyful communion. The film’s mantra—“the best thing about hitting bottom is that there’s only one way left to go, and that’s up!”—comes into full focus.

In this light, perhaps the art of failure is actually the art of grace. Failure is the place where we come to face to face with the fact that our identity must find its root in something other than sweat and effort, or creative output. For me, the answer to that question is inescapably religious. It may not be so for you. But whatever and wherever your predilection, this much is true: Lasting creativity is the fruit of approval. It cannot be the basis for it.

Come to think of it, maybe creativity isn’t even the right word. Maybe electricity is better:

COMMENTS

8 responses to “Unshackle the Should: An Overlong Post on the Art of Failure (and the Failure of Art)”

Leave a Reply

For those who were there, the Adam Phillips quote mentioned in the Q&A (via The Paris Review) was:

“Symptoms are forms of self-knowledge. When you think, I’m agoraphobic, I’m a shy person, whatever it may be, these are forms of self-knowledge. What psychoanalysis, at its best, does is cure you of your self-knowledge. And of your wish to know yourself in that coherent, narrative way.”

Really glad I read this!

Oh my, too much I could say about this one! Distance between person and project is so important. Realizing that I are not my project’s success or failure is what allows me to persevere in my work in this world, otherwise it’s just too scary to keep taking chances.

Hahahaha I “am” not my failure or success, nor am I my failure to proofread 🙂

What feels like too much pressure and causes me to just want to give up is the thought that I need to be more creative. Though at times I have suddenly received a good idea and planned a novel middle school French lesson