A first glimpse inside our Food & Drink Issue, by way of one Carrie Willard. The issues are flying off the shelf! Order up!

When my parents were married in the 1960s, advice abounded about home entertaining. Etiquette books and magazine articles included tips on how to invite guests from any social station into one’s home, what to wear when they arrived, and how to set the table for the occasion.

When my parents were married in the 1960s, advice abounded about home entertaining. Etiquette books and magazine articles included tips on how to invite guests from any social station into one’s home, what to wear when they arrived, and how to set the table for the occasion.

With a few notable exceptions (Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking comes to mind), the focus seems to have been more on the etiquette of entertaining and all of the rules associated with it, and less on the actual food. When food was featured, the emphasis seemed to be more on convenience (hello, Jell-O) or novelty (delectable treats like the Shrimp Christmas Tree) than the quality. Lipton Onion Soup mix and cake mixes in boxes promised space-age accessibility, if not haute flavor. If my collection of church cookbooks from that decade is any indication, Velveeta and minute rice were a dream come true; hot dogs were ubiquitous, and not in the gourmet hipster sense.

The countertop microwave oven was introduced in 1967, and quick-cooking recipes followed. My mother-in-law took a class about how to use her microwave, and my grandfather once tried to cook an entire leg of lamb in his microwave, and then wondered why it didn’t turn out so well. In an age like that one, who needed gourmet fare when there was Chef Boyardee and Kraft parmesan “cheese” at the ready? But for all the convenience and newly won free time, home entertainers just spent more time refining their place settings and handwritten cards—inviting friends and families to everything from a backyard picnic to a baptism brunch.

Cookbooks from this era have extensive instructions about hosting-etiquette, and often include a picture of the cookbook author herself on the cover, or a cartoonish outline of a trim housewife in an apron and high heels. The Family Book of Home Entertaining, published in 1960, advises young people who want to throw a dinner party:

If you are a young homemaker and your kitchen space is inadequate, or there is no helper to take care of young children while you entertain, or your … furnishings are still incomplete … don’t attempt a sit-down dinner.

In other words, if conditions are not favorable, or if you don’t have everything exactly right, then don’t even try. We can hear echoes of Downton Abbey in this advice. The Crawley family hosts elaborate formal dinner parties with the help of an extensive staff. In the first episode of the first season, the head butler (Carson) and his employer, the Earl of Grantham, discuss staffing deficiencies for the evening meal:

Carson: We may have to have a maid in the dining room.

Lord Grantham: Cheer up, Carson. There are worse things happening in the world.

Carson: Not worse than a maid serving a duke.

In Carson’s distress, and in entertaining advice in the decades that followed, it is easy to pick out the laws defining the expectations of the age. A certain self-righteousness could be earned by knowing the rules and following them correctly, and there wasn’t much room for the inconvenience of family life or staffing shortages. We can see, at least in hindsight, that there wasn’t much room for grace in those guidelines. But, lest we start self-righteously patting ourselves on the back for doing away with these antiquated ideas, we can find similar strains of rules at today’s table.

One hundred years after the fictional family lived at Downton Abbey, and fifty years after the advent of the microwave dinner, the etiquette quotient has been turned on its head. The 21st century tends to focus more on responding to texts and paperless e-vites than on the proper placement of forks and knives at the table. But this doesn’t mean we’ve eliminated the rules. To the contrary, we’ve just replaced them with a set of different ones. The food itself has taken center stage today. I don’t know if I’ve ever sent or received a hand-written invitation to dinner, but I do know I’ve fretted over which recipe I should choose and where my ingredients should be sourced.

In a fashion, we have created anti-rules for entertaining. With articles like “How to Throw a Crappy Dinner Party,” we opt for setting aside the old etiquette rules so we can enjoy our friends instead. Cookbooks today largely feature the food itself, encouraging readers to find the very best ingredients. There are full-color photo spreads of raw ingredients and plated food. Ina Garten, the Barefoot Contessa herself, has been chided for her admonition to use “good” olive oil or “good” mayonnaise, or “preferably homemade” chicken stock in her recipes. But while we are poking fun at these seemingly elitist instructions, we are also worrying whether we should use imported sheep’s milk or domestic cow’s milk feta to brine our free range chicken before roasting it.

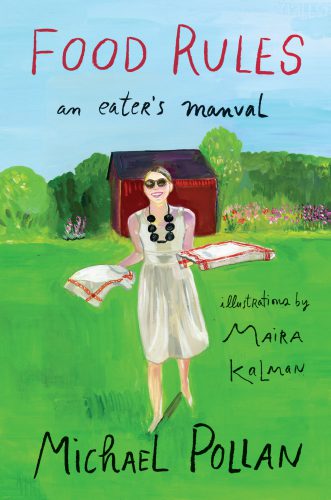

“Organic.” “Sustainably grown.” “Local.” These now-cliché descriptors have replaced place cards and ashtrays. Emily Post and the kitchen staff have been traded in for food writers and activists like Barbara Kingsolver and Michael Pollan. Wendell Berry, the essayist and environmentalist, famously called eating an “agricultural act.”[1] In a 2013 interview with The Atlantic, Michael Pollan credits Berry’s idea with his own interest in food journalism, saying it “formed a template for much of [his] work.” The author of that article, Joe Fassler, writes: “In [Pollan’s] hands, cooking is no longer a workaday chore: It’s alchemy, it’s revolutionary, and it’s what makes us human.” There’s quite a leap there, from recognizing the power inherent in our food choices to allowing them to define who we are. That leap also implies quite a bit of capability in human hands. Alchemy? Three times a day? That’s a lot to digest, both literally and figuratively.

I don’t disagree with Wendell Berry, that eating is an agricultural act. I don’t disagree with Michael Pollan that we “vote with our forks” three times a day when we participate in the modern food economy. But I have to take issue with the extrapolation from all of this that cooking food makes us human. In the beginning, God may have placed humanity in a garden, but he doesn’t require us to spend a certain number of hours per week planning meals there to remain fully human.

Along with all of the “good” olive oil and organic kale we should be eating, we are told we shouldn’t be eating high fructose corn syrup and (heaven forbid) trans fats. The “eat this” list rivals only the “don’t eat this” list, and both seem to be growing faster than the weeds we shouldn’t be killing with pesticides. We read in Romans 14: “The one who eats everything must not treat with contempt the one who does not, and the one who does not eat everything must not judge the one who does, for God has accepted them.” This was, of course, referring to religious observances relating to food, but it bears another look within the lens of contemporary judgments surrounding food and eating.

Today, I wouldn’t think twice about the etiquette of whether my husband or I should answer the door “when company comes,” but I’d certainly think long and hard before bringing a bologna sandwich on white bread for my workday lunch, even if it was “good” bologna and “the best” white bread. We buy locally, and ideally, we’d like to see the dirt under the farmer’s fingernails as he hands us our goods. And of course it’s not just us. Even fast food has taken the high road, in some cases. Elevation Burger is a chain of fast food hamburger restaurants featuring grass-fed, organic, free-range beef. The restaurant’s website claims, “We’ve elevated the typical burger joint standards so you can maintain yours.”

I noticed this kind of high-mindedness in myself when our family first subscribed to a farm share through a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program. We signed up for a growing season by writing a check to a local farm, and in return, they promised us a weekly share of the vegetables they grew. Everything was organic, and grown within a few hundred miles of our home. I felt a heightened sense of virtue as we planned meals based on the seasonal produce, and used everything in the box, including the carrot tops and beet greens. My sense of pride swelled as I drove to the neighborhood pick-up site and all but high-fived “our” farmers for providing such nutritious food for our family. Let me be clear: we enjoyed that produce, and cheerfully chewed through bushels of kohlrabi and kale. I think Community Supported Agriculture is a wonderful thing. But my own smugness was alarming, leading me to wonder whether the new sacred cow, our new golden calf, is 100% grass-fed, 100% grass-finished, sustainably sourced, and never treated with antibiotics or growth hormones.

There’s an implicit message in all of these food rules and high standards. And it echoes the message of the past: if you can’t do this well, then don’t even try. The thing we tried to do well then was hosting a dinner party with properly placed plates and knives, and the thing we’re trying to do well now can be just feeding ourselves. All of this pressure to “do it right” can lead to significant angst. In recent years, there has been an increasing incidence of what’s called Orthorexia nervosa, a psychological disorder characterized by “an obsession with healthy eating.” As The Guardian reported, the name of the condition itself reflects a yearning for righteousness and worthiness: “‘Ortho’ means right or correct, and ‘rexia’ means desire. In other words, a desire to be correct.”[2] According to a 2009 article in The Guardian, those who suffer from this condition are “solely concerned with the quality of the food they put in their bodies, refining and restricting their diets according to their personal understanding of which foods are truly ‘pure.’” People with this condition often have “rigid rules around eating.” The article continues:

There’s an implicit message in all of these food rules and high standards. And it echoes the message of the past: if you can’t do this well, then don’t even try. The thing we tried to do well then was hosting a dinner party with properly placed plates and knives, and the thing we’re trying to do well now can be just feeding ourselves. All of this pressure to “do it right” can lead to significant angst. In recent years, there has been an increasing incidence of what’s called Orthorexia nervosa, a psychological disorder characterized by “an obsession with healthy eating.” As The Guardian reported, the name of the condition itself reflects a yearning for righteousness and worthiness: “‘Ortho’ means right or correct, and ‘rexia’ means desire. In other words, a desire to be correct.”[2] According to a 2009 article in The Guardian, those who suffer from this condition are “solely concerned with the quality of the food they put in their bodies, refining and restricting their diets according to their personal understanding of which foods are truly ‘pure.’” People with this condition often have “rigid rules around eating.” The article continues:

The obsession about which foods are “good” and which are “bad” means orthorexics can end up malnourished. Their dietary restrictions commonly cause sufferers to feel proud of their “virtuous” behavior even if it means that eating becomes so stressful their personal relationships can come under pressure and they become socially isolated.2

The condition has been recognized relatively recently by the mental health community, and is described as a “fixation on righteous eating.” It is on the rise, but it is also very difficult to diagnose, because our culture as a whole is obsessed with categorizing food into “good” and “bad” categories. As a nutritional therapist said, “In our current food-obsessed culture, healthy eating can take on a quality similar to religious fervor, in which certain foods are sinful and eating in a certain rigid way is godly and rewarded.”

A “religious fervor.” Forget Downton Abbey! This isn’t an etiquette fad; this is a disorder. And while the disorder can now be named, it isn’t a new one: Julia Child said 50 years ago, “I think one of the terrible things today is that people have this deathly fear of food: fear of eggs, say, or fear of butter.” She also said: “The only real stumbling block is fear of failure. In cooking you’ve got to have a what-the-hell attitude.” Easier said than done, Julia, especially when our minds are whispering all of the rules we’d love to forget.

Whether it’s entertaining or recipes or agricultural activism, a set of written or unwritten rules can stain the natural grace that otherwise accompanies a table full of friends. These rules divide people by class and status; they can get in the way of real community. They can draw a sharp line, right down the middle of the dining room table, between saint and sinner.

With or without the self-righteousness of a CSA share, there’s also a natural grace—and great joy—in cooking and feeding people. I feel the same way that Julia Child did when she said: “I think careful cooking is love, don’t you? The loveliest thing you can cook for someone who’s close to you is about as nice a valentine as you can give.” I couldn’t agree more. I cook because it’s fun, and because it gives me something to create.

Cooking also keeps me humble. That high-mindedness I can sometimes feel for making the “right” food choices gets chipped away with every fallen cake or dried-out pot roast. Cooking reminds me that whatever we’re doing, we’re doing imperfectly, but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth doing. Why do we have children, knowing that they will have pain, and almost certainly have pain because of us, their parents, at some point in time? Why create? Why do anything? There is some grace in that, I think—grace in the meals we’ve shared with friends, even when, or maybe especially when, we’ve forgotten to set the table. There’s grace in a GMO-laden, non-organic peanut butter sandwich we’ve eaten over the sink when the meal doesn’t turn out as planned. There’s definitely grace in the laughter that comes at one’s own expense when things don’t turn out as planned.

When it comes down to it, this great joy comes from God, who gives us this gift of food. In our sharing of that gift, there are echoes of the same grace present on the night before Jesus died, when he hosted a meal for his friends. And surely those moments include the joy that must have been savored on the shore where Jesus shared fish with those same friends after his resurrection. There’s even a hint of Julia Child’s what-the-hell attitude in the Gospels: “When you enter a town and are welcomed, eat what is offered to you” (Lk 10:8).

Robert Farrar Capon—Episcopal priest, theologian, and food writer—experienced all of this in his own kitchen. His 2013 obituary in The Economist concluded with these words:

Food and company, he wrote, “don’t slake man’s thirst for being; they whet it beyond all bounds.” It was all part of the real work: “To look at the things of the world and to love them for what they are. That is, after all, what God does, and man was not made in God’s image for nothing.” Even the humblest meal could be a Eucharist, with the cook serving both as its priest and, through loving sacrifice of time and effort, its victim too.

TO ORDER THE MOCKINGBIRD’S FOOD & DRINK ISSUE, GO HERE.

https://youtu.be/2RMRSWL98bY

[1] Wendell Berry, What Are People For?

2 Olga Oksman, “Orthorexia: when healthy eating turns against you,” The Guardian.

COMMENTS

5 responses to “Orthorexia: The Fixation on Righteous Eating”

Leave a Reply

Bon Appetite to all my friends!

I see momma’s who obsess about ‘clean’ eating and do not share meals with their husband and children. Thanks for the insight into what is going on.