However many years a man may live,

let him enjoy them all.

But let him remember the days of

darkness,

for they will be many.

— Ecclesiastes 11:8

The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.

— John 1:5

I wake up mornings in the darkness, to get ready for work, or writing if it’s a day off. I let my wife sleep and I close the bedroom door after I press the switch for the hall light. I turn on all the lights in the kitchen, even the under-cabinet fixtures that have separate switches because it’s an old kitchen, and I added those lights myself. The dining room chandelier is on a dimmer, which I adjust as far up as it will go. There’s an old swag lamp I click on in the sunroom, the back-of-the-house addition I will remodel this summer. I leave on the porch lamp that illuminates the back deck out the window of the kitchen, where I sit at my tiled café table that gleams with reflected light, and drink coffee. Especially in the winter, when there is no early dawn in the windows, I can still feel the darkness pressing on me. I’m not afraid of things that come out of the dark or things that go bump in the night. I am struggling to shake off the sense of nothingness—for me a feeling of meaninglessness, abandonment, and solipsism—that often wakes up with me in the darkness and solitariness of ordinary life.

We pass our lives between two oblivions, from the darkness of birth to the darkness of death. In between is the everyday darkness of ordinary life, punctuated often and in many places by the deep darknesses of human folly and evil. Much of what we do with ourselves is just staving off the darkness, trying to avoid the seeming absurdity of life. Pleasure—sexual or otherwise, achievement—of fortune or ascending the summit of whatever humanly-designated dunghill counts for it, entertainment, self-improvement, sadly even many relationships. Often, they all serve only to distract us, from our knowledge that we are descending into night—gently or not, that we are all just slip-sliding away.

Ernest Hemingway wrote about this, sparsely yet eloquently, in what James Joyce once called “one of the best stories ever written”, “A Clean Well-Lighted Place”, published in 1933. Late night in a Spanish café, two waiters, a young man and an older one, watch and talk about the last patron in the place, an aged, deaf, dignified old man who drinks alone, “in the shadow the leaves of the tree made against the electric light.” A soldier and a girl—likely a lady of the evening—walk past in the street. The two waiters talk about the old man. His attempt at suicide, his money, his well-comported drunkenness, his loneliness, his need to linger a while longer. The young waiter is abrupt and impatient; he has a wife he wants to get home to. The older waiter understands; the old man wants to stay a little longer in this “clean and pleasant café . . . well-lighted. The light is very good and also, now, there are shadows of the leaves.” The younger waiter hurries the old man out. We follow the older waiter home, alone. In the street, he continues the conversation with himself. One needs a place that is clean and pleasant and has light. Why? “What did he fear? It was not fear or dread. It was a nothing that he knew too well. It was all a nothing and a man was nothing too. It was only that and light was all it needed and a certain cleanness and order.” He muses Hemingway’s famous parody on the Lord’s Prayer and the Hail Mary: “Our nada who art in nada, nada be thy name . . . Hail nothing full of nothing, nothing is with thee.” He pauses at a bar for a cup of espresso, but finds no respite; the light is bright, but the “bar is unpolished”; it will not do like a “clean, well-lighted café.” He will go home and, with the daylight, finally fall asleep.

The story is like a shot of straight bourbon, unadorned but subtly complex. An acquired taste. Seldom has so much been said in so little space. There is no plot in the traditional sense, little action, and minimal description. In less than 1500 words, almost all dialogue and interior monologue, Hemingway expresses the sensibility of an era of disillusionment, and evokes that sensibility in the reader, nearly erasing the line between literature and life, to paraphrase Joyce.

The sensibility, of course, is nihilism. Not a systematic philosophy, if you could even construct such a thing (though Derrida, Foucault, and Mark C. Taylor eventually tried), but a visceral response to the disenchantment, disillusionment, and sense of alienation now become endemic in modern Western culture; a gut reaction to the seeming silence of God and the indifference of the universe. You can’t really grasp fully the history of 20th century, and now 21st century, arts and literature without dealing with nihilism (anymore, you can’t really understand the contemporary postmodern carnival without taking into account its insouciant absurdism. Nihilism with a smiley face. But that’s another story, perhaps a sequel to this one). Serious nihilism touched writers from Twain (the book to read is The Mysterious Stranger), to Kafka, Camus, Kurt Vonnegut, Douglas Adams, and David Foster Wallace. Not that they all preached nihilism (though a case might be made for Vonnegut and Adams as evangelists); but they all felt it, like darkness with weight.

It was a sensibility Hemingway owned (as I have written about here). As Hemingway biographer Kenneth Lynn put it, Hemingway embraced a “pessimistic religious vision which stressed that human life was hopeless, that God was indifferent, and that the cosmos was a vast machine meaninglessly rolling on into eternity.” In a “Clean Well-Lighted Place”, between the darkness and the darkness, all we can hope for is a bit of light and a little dignity, and the only “grace” is acceptance. In his own life, Hemingway succeeded more than most in heroic self-making; a bravura performance that blurred the lines between writer and actor. Hemingway enlarged into fiction what he had lived in life, then tried to live in the fictional world he created. I think he knew all along what he was doing, and if in the end he was not startled at his failure, he was still deeply disappointed that the darkness overcame him. And I think one reason that happened was because Hemingway could never acknowledge any transcendent reality, whose uncreated light might peek around the penumbra of the world’s shadow, in signs and sacraments. When the world of his own making crumbled, and the light of his own artifice faded, Hemingway could see and feel only the darkness.

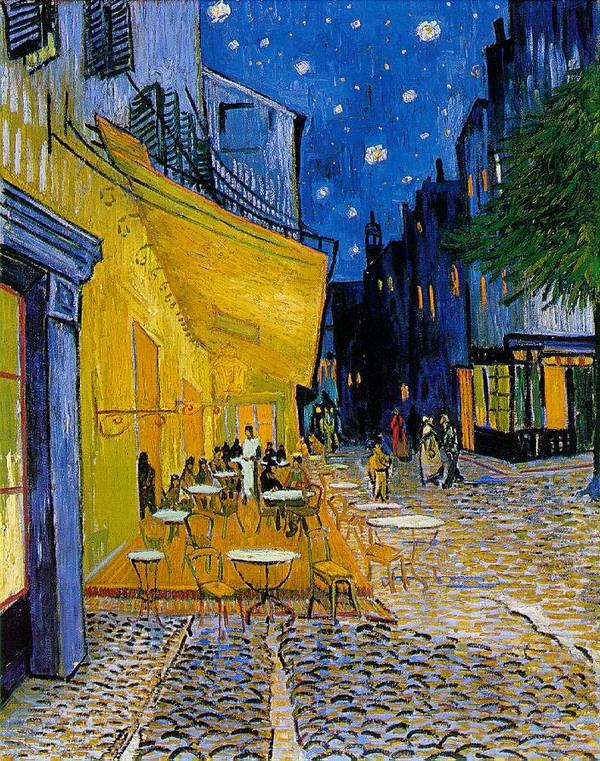

Beside my bed, just above the lamp on the nightstand, there is another clean, well-lighted place. I have hung there a small print of Vincent van Gogh’s Café Terrace at Night (The Café Terrace on the Place du Forum, Arles, at Night). It is often the last thing I look at, just before I switch the lamp off and drift off to sleep.

Vincent painted Café Terrace at Night in September, 1888, after moving to Arles in the south of France that past February. He had hoped to found an artist’s colony there, for both spiritual and financial support. This endeavor was a failure, as all Vincent’s entrepreneurial, relational, and existential endeavors had been (as I have written about here). He had a violent falling out with Paul Gaugin, the only artist he could persuade to join him, and it was in Arles that he cut off his left ear and gave it to a prostitute.

Vincent painted Café Terrace at Night in September, 1888, after moving to Arles in the south of France that past February. He had hoped to found an artist’s colony there, for both spiritual and financial support. This endeavor was a failure, as all Vincent’s entrepreneurial, relational, and existential endeavors had been (as I have written about here). He had a violent falling out with Paul Gaugin, the only artist he could persuade to join him, and it was in Arles that he cut off his left ear and gave it to a prostitute.

But it was also in Arles that Vincent produced almost two hundred paintings from 1888 to 1889, including some of his most iconic: The Sower at Sunset, Fishing Boats on the Beach at Saintes-Maries, his sunflower still lifes, The Night Café, Café Terrace at Night, Starry Night Over the Rhone, and Chair with Pipe.

Like Hemingway, van Gogh envisions a respite of light in the darkness, and a space and time of calm order. But the Café Terrace is different. In “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place”, “everyone had left the café except one old man who sat in the shadow the leaves of the tree made against the electric light”, and he drinks alone, and in silence “because he was deaf.” But Vincent emphasizes (as best as Vincent can) human connection. The patrons at the café cluster together, leaving empty the seats closest to us. We can imagine the clink of cups and quiet conversation. A couple meet and talk in the middle of the cobbled street. They are all bathed in the warm glow of a large gas lantern, made a focal point by Vincent’s heavy impasto of sulfur-yellow, illuminating the café wall and terrace awning, and throwing its light into the street.

There is another difference. Hemingway’s perspective remains resolutely earthbound, and the “action” of the story follows a descent into the dark interior of the old waiter’s struggle with the nada. In Café Terrace at Night, the viewer’s eye is led, by the painting’s one-point perspective, from the foreground onto the well-lighted terrace, then to the waiter standing amidst the night patrons. Past the terrace, the light fades down the street, where a horse and cab emerge out of the darkness. Where the street is darkest, only a few dimly lit windows relieve the gloom. But as the eyes ascend the blank walls of darkened buildings, they finally rest on a deep blue night sky, alive with blazing stars.

Café Terrace, painted in mid-September 1888, shows the second time Vincent painted a night sky with stars. The first, two weeks earlier, was Portrait of Eugène Boch. In this painting, the ultramarine sky with a few dots and splashes of white and yellow paint serves mainly as a backdrop to Vincent’s depiction of his artist friend. But even here, describing in August his plan for this work to his brother Theo, he writes, “Behind the head — instead of painting the dull wall of the mean room, I paint the infinite” (italics added). After Café Terrace, Vincent painted Starry Night Over the Rhone in late September. The scene is real life; the Big Dipper hangs in the sky over the gas-lit shoreline of the town, and Vincent makes the sky and stars sparkle and shimmer with painterly effects. Like Café Terrace, he painted Starry Night Over the Rhone ein plein air, at night, under the gas lamps of Arles. Vincent’s next and final rendition of a starry night sky became his most famous; The Starry Night, painted in June 1889 when he was still confined at the Asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole in Saint-Rémy, about twenty miles north of Arles.

A starry sky signified always to Vincent the infinite; the transcendent reality one looked through the natural world to see. During his period of religious fervor, while he trained for the ministry in Amsterdam in 1877, he described to Theo his living situation, and how “In the evening there’s also a beautiful view of the yard, where everything is deathly still and the street-lamps are burning and the sky above full of stars. When all sounds cease – God’s voice is heard – Under the stars.” After he turned to art for salvation as well as vocation, he would write in Arles in June 1888, “I have an immense need for (should I use the word) religion; and then I go out at night into the open and paint the stars, and I always dream of such a picture, with a group of lively friendly figures.” Mid-August, a month before he painted Café Terrace, Vincent mused on his life, in the third person: “If you’re well, you should be able to live on a piece of bread, while working the whole day long, and still having the strength to smoke and to drink your glass; you need that in these conditions. And still to feel the stars and the infinite, clearly, up there. Then life is almost magical, after all.”

Café Terrace at Night combines the starry night and a “group of lively friendly figures” in a way that is aesthetically deeply pleasing. The one point perspective—slightly modified to highlight the heavy linteled doorway in the foreground—draws your attention into the painting, past the lighted terrace, down the darkened street, and up into the starry night. There is a textbook presentation of complementary colors—the gold-yellow of the terrace with its broad overhanging awning against the blue-violet of dark buildings and night sky. The way the changing colors of the cobblestones suggest the light thrown from the terrace lamp, the suggestive arrangement of figures, the highlights in the green tree branch, the tonal variations of the night sky—it all comes together as a harmonious and satisfying whole.

Vincent painted, selectively and with some artistic license, what he saw in Arles that September night, but I think what he saw signified to him the hope of fulfillment for his two greatest longings: the presence of God and the intimacy of friendship and family. In the darkness, he painted the stars, under which you could “feel … the infinite” and “God’s voice is heard.” He painted a clean, well-lighted café, “with a group of lively figures” surrounded by the night, sharing the warm light.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UMKORUXOKIw

Unlike Ernest Hemingway, Vincent van Gogh never gave up on a “sacramental” universe; a finite natural world in which earthly things—stars and gaslight and café patrons, boats on a Mediterranean beach, rough peasants sharing a meal of potatoes, irises and sunflowers—signify truly a transcendent infinite reality. In aesthetics and artistic technique Vincent presaged the development of modern 20th century art. He influenced the later post-Impressionists, the Fauvists, German Expressionism, even Abstract Expressionism. But in theological sensibility and felt philosophy he embraced Medieval typology, an approach to interpreting not only Scripture, but history and life. In his review of Ephraim Radner’s new book, Time and Word: Figural Reading of the Christian Scriptures, Peter Leithart, citing Radner, explains, “Typology also extended to the natural world, now seen as ‘an ordered whole, if grasped from a spiritual perspective, where everything must (and does) in [f]act refer to everything else. The universe exists as a ‘language’ in and of itself, given that reality is a kind of divine speech before all else’.” Typological interpretation encompassed not only history, events, and time, “but also ‘natural object[s] and fabricated artifacts’.” For Vincent, not only the Bible and the world, but his art itself, could be “divine speech”, referring to the “infinite” and to God.

Vincent’s problem was not that he saw signs and symbols of transcendent reality everywhere, but that he went a leap further and believed in a sort of magical sacramentalism. He believed that his painting, the act and the object, could create the reality he so longed for; that what he put on canvas would inevitably find its way into the real world, into his own pain and darkness. Art as the means of grace. But art cannot bear this causal burden, and Vincent—whose family circumstances, existential sensibilities, and emotional dysfunction were unrelenting sources of genuine personal misery—must have realized this at some point, the realization draining any hope he had that the world would requite his love and longing. As early as the winter of 1884, after another year of disappointments and difficulties, Vincent declared to Theo, “I would not expressly seek death . . . but I would not try to evade it if it happened.”

In their definitive biography, Van Gogh: The Life, Steven Naifeh and Gregory Smith present a compelling case that Vincent’s death in Auvers, France in the summer of 1890, was not suicide, but an accidental shooting. When the wounded Vincent was asked by the police, “Did you want to commit suicide?”, his answer was strange and vague, “Yes, I believe so.” Naifeh and Smith are convinced that Vincent lied to protect the shooter, a local teenager, from repercussions and possible imprisonment. In the end, they conclude, “Vincent welcomed death.” For Vincent—“a wayward, battered soul: a stranger in the world, an exile in his own family, and an enemy to himself”—the light of the stars and of a café terrace were not enough.

In their definitive biography, Van Gogh: The Life, Steven Naifeh and Gregory Smith present a compelling case that Vincent’s death in Auvers, France in the summer of 1890, was not suicide, but an accidental shooting. When the wounded Vincent was asked by the police, “Did you want to commit suicide?”, his answer was strange and vague, “Yes, I believe so.” Naifeh and Smith are convinced that Vincent lied to protect the shooter, a local teenager, from repercussions and possible imprisonment. In the end, they conclude, “Vincent welcomed death.” For Vincent—“a wayward, battered soul: a stranger in the world, an exile in his own family, and an enemy to himself”—the light of the stars and of a café terrace were not enough.

We are all looking for clean, well-lighted places to call our own, at least for a while. Vincent never found one. To read his story, and his hundreds of letters, is like following a picaresque anti-hero through one soul-lacerating situation after another, dripping paintings like blood drops, until he succumbs to the world’s wounds.

Hemingway had many. Spain and Key West and Cuba and Ketchum, Idaho. Most of all, Paris, where Hemingway began his writing career and when, with his first wife Hadley Richardson, they “were very poor and very happy”, as he wrote as the very last words of A Moveable Feast, the memoir published after his death. Especially the café on the Place St.-Michel, where he would go and write. Nearly forty years later Hemingway wrote, “It was a pleasant café, warm and clean and friendly, and I hung up my old waterproof on the coat rack to dry and put my worn and weathered felt hat on the rack above the bench and ordered a café au lait. The waiter brought it and I took out a notebook from the pocket of the coat and a pencil and started to write.” That’s how Hemingway remembers it. The epigraph on the title page of A Moveable Feast comes from a bit of conversation in a bar in 1950, remembered by A.E. Hotchner: “If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast”.

But Paris can’t really stay with you. Or a starry night sky in Arles, or New York, Los Angeles, Key Largo, Chincoteague, St. Thomas, the café by the theater, the Starbucks down the street, or any of the thousands of places we look for rest and light and calm and order. What we find can be true and good and push back the darkness for a time. But they are always and only fleeting feasts. Eventually, all lesser lights fade. The place of lasting light and true remembrance is in the celebration of the Eucharist. It orders our disordered lives and reminds us that the reality and relationship we long for have already been created for us.

I get up most mornings in the dark. Especially on those mornings when my wife remains in bed for a while, I feel solitary and lonely, a stranger in the world; I feel the nothing. I turn on all the lights and the nothing retreats a little. I sip a cup of coffee and, if I still feel lonely, at least I find some comfort in the warmth and taste and aroma. I read the digital equivalent of a newspaper, and the nothing, the darkness and disorder, gets named. I read Scripture—for now it’s the Gospel of John—and the Word as sacrament reminds me I am not drinking alone in the dark; I am in a clean, well-lighted place.

COMMENTS

5 responses to “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place”

Leave a Reply

If the nihilists only grace is acceptance. It’s seems that then must be Gods (and the Christians) first grace to the world. Thank you jesus

“But Paris can’t really stay with you.” Ain’t that the truth. This is a profound and comforting and beautifully written piece, and I will remember it. Thank you.

What Ken said.

Calling Hemingway a nihilist is a TOTAL misunderstanding of Hemingway. I recommend you read, Hemingway’s Dark Night: Catholic Influences and Intertextualities in the Work of Ernest Hemingway. It provides a more nuanced and sophisticated approach to Hemingway than is provided here.