There was a period of time, and I’m not proud of it, when the worst insult my friends and I could lob at a person/place/thing was that they were ‘pretentious’. It connoted everything we didn’t like: phoniness, humorlessness, and haughtiness.

At least, in theory it did. Over time, the word became less of a spear and more of a shield, fending off anything that made us feel bad about ourselves. That grad school student who disagreed with our opinion? Pfff, pretentious! That girl who wouldn’t give us the time of day?! So pretentious. That writer who slagged off Guns n Roses in print? I bet he’s a Yankees’ fan (translation: ueber-pretentious). At one point, I think we classified everyone who had a cellphone as pretentious. Don’t even ask me what epithets we reserved for bloggers.

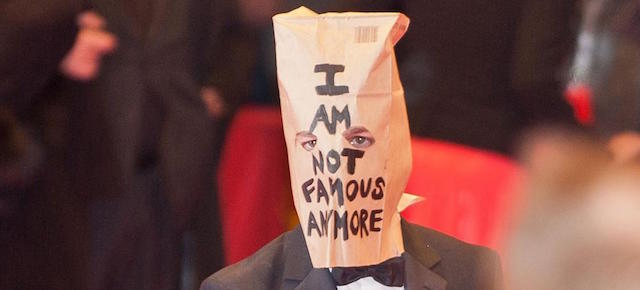

Then social media took over our lives–or maybe we just grew up–and the word lost its bite. The Internet made it impossible to pretend we weren’t all pretending, pretty much all the time. Our practiced unkemptness was revealed to be just as much of a pose as the manicured facial hair of those Eurofied former hallmates. Our disdain for overambitious careerists, overindulged socialites, and overearnest activists merely a different form of superiority. We were no less pretentious than any of them, no more ‘authentic’.

In fact, the comparisons didn’t make sense; self-construction was simply the water we were all drowning swimming in. Before long, Madison Avenue was selling us new shoes and better shaving cream butter on the basis of their ‘authenticity’, thus compounding our cynicism all the more.

I write this by way of introducing Barrett Swanson’s masterful essay “Act Naturally: Pretentiousness, Coolness and Culture” in the LA Review of Books. The occasion for the essay was the new book Pretentiousness: Why It Matters by Dan Fox, itself an attempt to reclaim the word’s potency.

Swanson took the opportunity to muse on where this preoccupation with (and enthronement of) the Real Self has gotten us. He opens with an anecdote about an advertisement promising him that the “The Real You Is Sexy”(!), a remarkable statement whose groundwork is worth tracing:

Where to find this “real you”? And, upon its discovery, how best to communicate it to the world? This anxiety has a long pedigree, first arising amid the revelations of the Enlightenment, when individuals were no longer beholden to the stiff hierarchies of feudalism but could tear away the garments of their socially determined roles in order to reveal their authentic selves.

While the notion of liberal individualism was a midwife to Western democracy, its insistence on authenticity ultimately proved to be an impossible existential struggle…

Never before in history, one could argue, have individuals been so acutely conscious of the extent to which personhood is performed, especially when one is constantly swiping through social media platforms in order to monitor, with fussy custodial care, the dazzle and sheen of an online persona. “Our culture demands total transparency, at the same time that it demands near-constant performance,” the philosopher Michel de Certeau writes in his book The Practice of Everyday Life. “So how can you know a person?”

This existential slipperiness of personhood is one reason why the art critic Dan Fox, in his new book-length essay Pretentiousness: Why It Matters, feels justified in debunking the rhetoric of “pretension,” a word that is typically leveled as a pejorative. After all, if inauthenticity is our shared fate and all social encounters are unavoidably performative, on what grounds can anyone call out another’s acts of cultural deception?

Because there is no Platonic ideal, no unblemished paragon waiting for us on the far side of shams and imposters, any judgment of authenticity or accusation of fraudulence should, in Fox’s opinion, be stubbornly regarded as just so much arrant nonsense. “When a person decides that a restaurant is pretentious,” he concludes, “the ‘authentic’ restaurant to which it’s being compared and the values that provide The One True Restaurant with its bona fides are seldom revealed.”…

The strictest form of legalism, you could almost say, is the kind that lacks a discernible law to fuel it and instead appeals to highly subjective abstractions like ‘authenticity’. But that’s not all:

In the United States, the engine of prosperity has always been its bootstrap logic, a fierce belief in the power of self-determination. It’s taken for a fact that if you wish to succeed in this country you must not resign yourself to the small-town myopia of Jimmy Gatz but must pursue, with pathological determination, the urbane mythomania of Jay Gatsby. Which is another way of saying the metabolism of the United States runs on the empty calories of self-delusion, and the main reason why pretentiousness doesn’t hold a prominent place in our imagination is that, in a supposedly “classless” United States, a citizen finds himself in an eternal state of transubstantiation, endlessly scrabbling up the social ladder toward some next higher echelon of selfhood — one that is usually denoted by the altitude of one’s tax bracket.

It’s at this point that Swanson takes up Lee Konstantinou’s Cool Characters: Irony and American Fiction, a formidable volume which examines the literary archetypes that have attempted to address the spiritual vacuum left by “the stampede of liberal secularlism” and accompanying triumph of “the chilly tenets of scientific materialism”. He lists five, and they’re immediately recognizable: the hipster, the punk, the believer, the coolhunter, and the occupier.

If the search for the Authentic Self has become our prevailing replacement for God–i.e. a potential, and troublesome, locus of absolute truth–then these five character categories represent five competing belief systems (or what we might call religions). Sadly, they have not proven very reliable:

Allergic to dogma and resolutely opposed to degrading effects of ideology, the hipster was “defined more by what he disavowed or stood against than by what he fought for.”

The problem with the hipster, as history has made clear, was that [it]… became just another style, an attitude susceptible to the very forces of establishment co-optation that the hipster’s eccentric strategies of parody and slang sought to avoid… The outlook of nonconformity would inevitably be repackaged as a “consumption ethic,” since “self-expression and paganism encouraged a demand for all sorts of products — modern furniture, beach pajamas, cosmetics, colored bathrooms with toilet paper to match.”

Same goes for the Punk. Things really shift into gear, however, when he unpacks the Believer and the Coolhunter. The former, it turns out, cannot be discussed without mention of David Foster Wallace (AKA Alan Moore’s latest obsession!) and his concerted pushback against post-modern overdependence on irony in both books and life:

The Believer: the paradox of Wallace’s own fiction, as Konstantinou argues, is that while it sought to defend the spiritual advantages of belief, it never adumbrated a doctrine of values that might be worth espousing in the first place. His idealism was a form without substance, an elegant but empty frame.

In the early years of the 21st century, the believers were supplanted by a new squad of literary characters that Konstantinou calls “the coolhunters,” …These coolhunters are deeply conflicted creatures, centaurs of competing ideologies. Young, ebullient, and extremely well-educated, they yearn, like the believers, to discover new forms of “authentic” self-expression…. [maintaining] a radical faith in the doctrine of self-fabrication… But unlike their earnest predecessors, they have resigned themselves to the neoliberal market and live out their days amassing subcultural capital that they can repackage in mass-consumable form to be sold for profit at retail centers across the United States.

In this depoliticized market culture, where products are untethered from social or religious moorings, individuals are free to select beliefs from a buffet of bespoke politics and à la carte theologies. Brand loyalty becomes a weak surrogate for religious allegiance or ideological commitment…

(Note: These coolhunters sound a whole lot like “Yuccies” AKA Young Urban Creatives).

It’s difficult not to feel as though we, as a culture, have reached a dead end, that our quest for authenticity has bred nothing more than a series of postures and attitudes that, if they hadn’t sprung up by themselves, would have been invented by market demographers anyway. Perhaps we are stuck in the age of “cool,” when all roads to larger causes inevitably circle back to the adolescent project of exalting the self.

That’s about as clear and compelling a critique of subjective sovereignty as one is likely to find–and it deserves a wider airing, not just because he’s right, but because of the suffering and pain this mode of existing causes. We reinforce the prison of the self at a serious cost to, well, ourselves. Those bars hurt like hell, as spiky as they are translucent. Not that any of us are choosing to live there–at least not fully. Our predicament is both inherited and engineered.

One of the chief ironies of what Wallace calls “our own tiny skull-sized kingdoms” is the (internal) oppression they afford under illusion of (external) liberty. Or you might say, the pricetag of personal authenticity appears to be crushing loneliness and narcissism, where no one can understand you, where everyone is an other. Terrible soil for love to blossom.

Then again, our anxiety about the Real Self certainly casts Christ’s line about ‘freedom for the captives’ in a flattering relief. The freedom to which Jesus refers, of course, is significantly richer than the absence of constraint. It is something far more absolving and counterintuitive, almost the inverse of the “tiny skull-sized kingdom”. Wallace outlined its possibility in his final work, which is where Swanson returns at the close of his essay, driven by the sense that Konstantinou may have sold the Believers short:

Published posthumously after its author’s suicide in 2008, [The Pale King] concerns a group of IRS agents in rural Illinois who subject themselves to soul-withering drudgery in order to complete the thankless task of balancing the nation’s accounts. At the center of the book is a character named Chris Fogle, a product of a 1970s suburban upbringing in Chicago, who is a self-professed “wastoid” — “the kind [of nihilist] who isn’t even aware he’s a nihilist.” Through a fog of prescription drug abuse, Fogle coasts through his adolescence, sneering at Christian classmates for their odious naïveté and reserving a special condescension for his father, a boring Ward Cleaver type. One might say Fogle is a mongrel of countercultural pretensions, a composite sketch of the postwar literary archetypes that Konstantinou describes… Like a good punk, Fogle believes that nothing really matters, which justifies spending long, vegetative afternoons getting stoned in front of the television, tripping on Obetrol and watching As the World Turns. He’s come to believe… that because identity is malleable and no cause is better than any other, he should simply pursue whatever happens to “interest” him at any given moment.

It’s during one such afternoon, when the program returns from a commercial break, that Fogle finally awakens to the meaninglessness of his existence:

I knew, sitting there, that I might be a real nihilist, that it wasn’t always just a hip pose. That I drifted and quit because nothing meant anything, no one choice was really better. That I was, in a way, too free, or that this kind of freedom wasn’t actually real — I was free to choose “whatever” because it didn’t really matter. But that this, too, was because of something I chose — I had somehow chosen to have nothing matter […] If I wanted to matter — even just to myself — I would have to be less free, by deciding to choose in some kind of definite way.

Becoming an IRS agent might seem like an unexpected route out of this cul-de-sac, but Wallace renders Fogle’s decision to join the “service” with spiritual undertones, lending it the tenor of a religious conversion. (It is a Jesuit accounting professor who sways him to this profession.) In the end, what endows the decision with value is that it requires “the loss of options, a type of death, the death of childhood’s limitless possibility, of the flattery of choice without duress.” Ultimately, Wallace characterizes the IRS as a form of civic engagement that can be seen to embody the burdens and virtues of adult life: “Effacement. Sacrifice. Service.” Far from flimsy abstractions, these battered terms do not promise the feel-good consolations of belief for belief’s sake. Instead, at least within the moral universe of the novel, they are enacted through a discipline of other-directed action. For Fogle, as for Wallace, salvation comes through the act of committing yourself to institutions that lie outside the evanescent whims of the self.

We might go one step further than dear old Wallace, may he rest in peace. Yes, salvation comes through an act of fatal submission–but it is not out of our commitment to Another but Another’s to us. We are the object of this shining act, not its subject. Mercifully and miraculously, nothing about it is predicated on our pretenses and poses. No mere literary device, in other words, but something true, and dare I say, Authentic.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Pretentious Believers and the Law of Authenticity”

Leave a Reply

David, this is good. I truly enjoy both your subject matter and your writing. This reminds of the classic line from “Life of Brian,” not sure if you’re a fan, and claiming myself to be a Monty Python fanatic probably places me smack-dab in the middle of the pretentious “hipster” category. Whatever… here’s the dialogue, “We are all individuals… (response) “I’m not.”