This post comes to us from Geoff Holsclaw, who was featured on the Mockingcast last week. Geoff is Affiliate Professor of Theology at Northern Seminary, and just published Transcending Subjects: Augustine, Hegel, and Theology. He is also co-host of his own podcast, Theology on Mission.

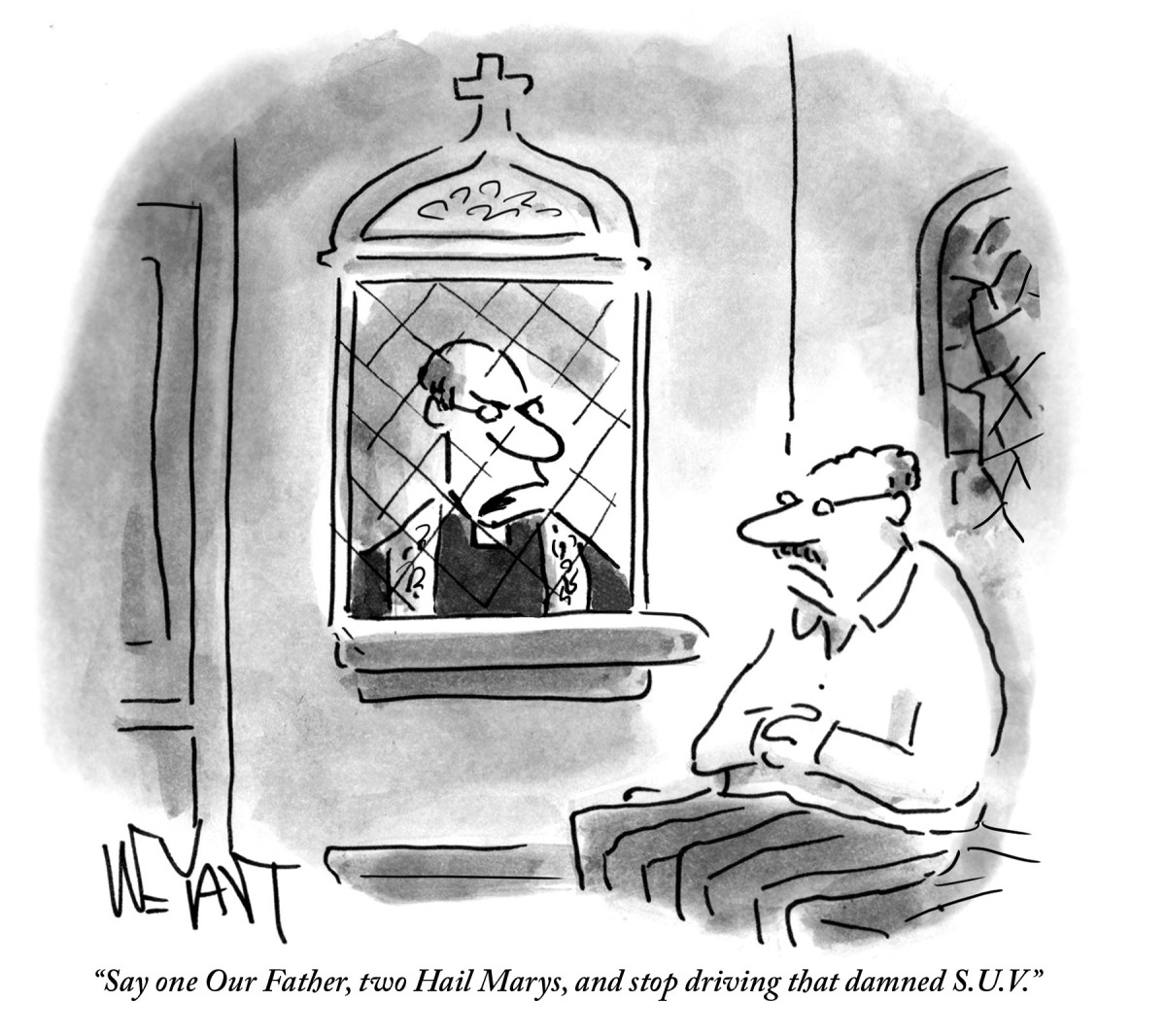

From the confessional at church, to the therapists couch, and now in every public setting, we confess ourselves. It is the civilized thing to do.

Of course we bear our hearts without understanding them. We offer our souls without having grasped them. We confess our selves without really knowing them.

Truly I say, confession has become our new creed, and yet it is a creed that comes without content.

Before Confession

What do we mean by confession? Well, let’s think of words. From the earliest days we grapple with words. As a toddler grasping after toys, the struggle with words is a grappling after desires. Fumbling with tiny fingers for a firm grip, our few words seek to explain our longings: food, sleep, a pleasure, a pain. What we cannot yet say, but experience (in both abundance and scarcity), is the desire for love—for connection, for care. Words express what we want, but rarely what we desire.

Unique to humanity (not just in the fact that we make tools, but that we make words, for that is all words are—or are they?) is the tendency for our tools to turn against us. We crawl into culture, attempting to stand amid the shifting sea of a civilized life, gathering our words for support. But we quickly find that our words become weapons and our longings the victim. Indeed, what we thought was most intimately ours—our own desires—become intruders and impostors. The words and desires, we learn, are from another—and we learn to hide and lie and fight and die with our words.

In the beginning the words say, “You are (fill in the blank)!” And we believe them. But the gap between the words we use and the reality we experience leaves a vacuum, one that we try to fill with our ardent confession, a confession of the self, a confession that affirms or renounces the words spoken over us.

The Words We Wear

We then take these confessions and put them on as garments carefully assembled according to the latest fashion.

Do we read our tabloids and watch talk shows to ridicule those other “confessions” poorly worn (“they look SO ridiculous”)? Do we watch our premier movies and primetime shows searching for an idealized confession (either sinister or sincere) and fantasize about our similarities with them? Do we scroll through our Facebook and Pintrest feeds for trends in the latest forms of self-affirmation, hoping to add flare to the clothing of our confessions? Do we seek therapists to tailor our confessions more properly to the body of our desires?

Of course we don’t know whether these garments express a secure self or cover an ashamed self. Indeed, we are taught never to ponder such a difference. We must instead affirm our confessions, our “stories”, deem our word-wardrobe fit for princes and not question whether we are being fitted as prisoners.

Daring Nakedly

For Augustine, confession is not a daily dressing of the words we decide to wear (speaking of which, today we are encouraged to change “selves” as often as underwear—and for the same reason). True confession is to disrobe, to become naked. Confession, for Augustine, is to bare all, to tell the naked truth. Confession is to bare the truth of the self: to be exposed to and endure the truth.

Let it be noted straight away that Augustine is not the father of modern autobiography, nor the contemporary conception of the will (i.e. freedom is the will to choice between options). To write of oneself was not Augustine’s invention, having much older precedent in other philosophical writings. The autobiographical material found in his Confessions is merely to situate himself as an authority for interpreting the sacred writings (Genesis 1-3) that end his Confessions, and to offer his own communally based conversion as a model for others (i.e., that only in community we find ourselves). Indeed, while modern readers ask “Why those weird philosophical reflections at the end of such an interesting personal account?”, ancient readers would have thought, “Why is the personal introduction SOOO long before the philosophical reflections?” Similarly, many think Augustine invented the modern “free will”, disconnected from any vision of the good or basis in reason. But this is merely a textbook cartoon perpetuated by those seeking to villainize Augustine for being a proto-Cartesian, and the creator of all the ills of Western society (and certainly there are many such ills, but not all belong at the feet of Augustine).

When it comes to confession, for Augustine, we could say that we always dress ourselves privately, but can only undress publicly. Or better, in community. We only come to know ourselves through a community that helps us to really see our “selves”, something we cannot see alone.

This of course chafes against conventional wisdom. We see community and society as the place of oppression and exclusion, of attempting to shape you into its own form, and the first commandment is to resist such maneuvers and to declare your independence by fashioning your own confession. (Ironically, “conventional wisdom” of this type is exactly the wisdom of a social group, its “status quo”, so to be authentically an “individual” is exactly what the community has programed you to do.) The greatest commandment of our age is to dress your “self” as you want, and to be addressed as you demand to be addressed. This is the confession of our civilized life.

We could say that confession these days is done by oneself for others (that you may be seen and known by them; indeed, every confession is now a demand to be recognized). But for Augustine, confession is done before others for the benefit of oneself (that you might see and know yourself). A confession that demands to be recognized rarely recognizes itself, and often becomes a parody of itself.

After Confession

What, then, comes after this confession? What comes after a confession which confesses nothing (but itself)?

First, silence. Then, more silence. Finally, more silence.

Augustine says the restless wandering with tattered words must come to an end. Let the clamor of confession cease. Let the soul searching for itself listen. Only then will the echoes within yourself end, the voices that have been housed within you for far too long.

Then, after the silence, you listen. Listen to others about yourself. Find those who speak the truth, neither pandering to your need to hear something flattering nor to either own need to flatter themselves by criticizing you. Find those who speak the naked truth so you might see yourself as you are.

Finally, receive another word, a better word, a word become flesh. As a fully human word, he comes to us in our need, our nakedness, our distress. As truly divine Word he comes full of grace and truth. As Augustine would say, Christ put on our coat of flesh so that we might be clothed by the word of God.

This, then, should be our confession. Not that we confess ourselves, but that we always confess another, the true Word who brings life and light to the world.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply