This one comes to us from Mickey Haist Jr.

“Every year is the same / I feel it again / I’m a loser / No chance to win.”

Hearing these words at my first concert, at age fourteen, is a powerful experience.

Quadrophenia, the rock opera album on which these lyrics can be found, is my favorite in The Who’s catalogue. It’s the crystallization of the band’s ethos: loud, but sad; at once hopeful and wistful. Its story is vague enough that any teenager, or former teenager, can find their own story reflected in it. That’s one of the great skills of Pete Townshend. He could write directly to an emotion, but couch it in a broad story so that every listener had the chance to identify with the characters. He knew that emotions without stories were not compelling so he created characters and stories to host his elegant explorations into fairly common emotions for teenagers and, again, former teenagers. In other words, it’s all about the wist.

At fourteen, I was already a few years into my obsession with The Who. What first grabbed me was probably the sheer power. They rocked. Loud, angry, violent. These are the features my peers found in video games, I think. I found them in an ancient rock group, who had broken up several times before I was even born.

These lyrics, from the song “I’m One,” hit me pretty directly. It’s a pretty rocking tune on the record, but it’s done as a mostly acoustic number live. At least, the version I had was acoustic, from a CD of a Pete Townshend solo concert. The difference in tone is arresting. In the midst of rock standard after rock standard stands this quiet plea for relevance, a prayer for acknowledgement. Jimmy, the hero of Quadrophenia, makes his last stand for sanity on this rock: “I can see, that this is me. I will be. You’ll all see I’m the One.” Such a simple set of declarations made real by Pete’s voice, made real by Pete’s guitar, made real by the context of the record and of the band, and finally, made real by the fans creating a mighty chorus of losers, singing and screaming for their voices to be heard, and if not heard, then to become a part of something that is heard, to become a part of something that is powerful.

Transitioning from middle to high school saw me using The Who more than ever. This song summarized my fears and hopes. Every girl that rejected me, every girl that I never talked to, every assignment I screwed up, every awkward squeaking of my damnable voice, every time I was told to shut up, and every time I felt like I was told to shut up was imprinted on this record, encoded in 1973 for me to discover in the late 1990s as a treasured medical kit for my fragile soul.

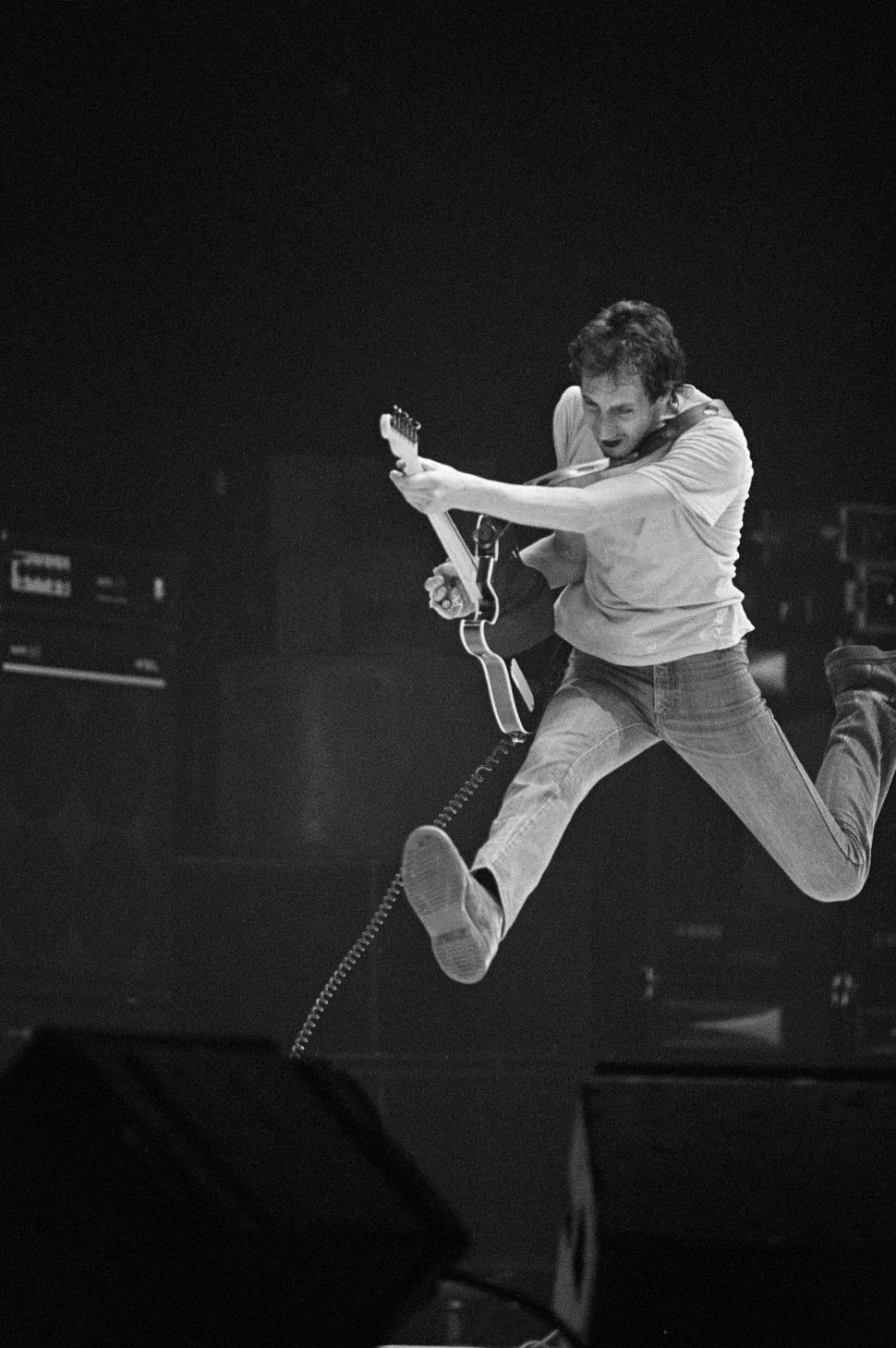

In the summer of 2000, at the age of fourteen, I saw THE WHO LIVE. Anyone who has ever been to a show knows why it must typed in all caps. Five guys on stage, three of them were part of the original group. Rabbit, the keyboard player, had been with them since 1979. The drummer was newish.

Zak Starkey, son of Ringo Starr, pupil of Keith Moon’s. I loved the new members. I loved John on bass and Roger on vocals. But I was there for Pete Townshend. This was my chance to be in the same room with the man that had provided comfort to me during (what I thought was) my hardest year. It was a profound moment, not just some concert. Certainly not just some classic rock reunion tour. This was a chance for a million others like myself to be with the hero who dropped a line of solidarity into our teenage wastelands. I stuck my nose up disdainfully at the people wearing Journey T-shirts and people wasting this experience by smoking pot. Didn’t they know how important this was to me? They’re polluting my air space with drugs and the memory of terrible music!

That song, “I’m One,” moved me at that first concert. I teared up a bit. A teenager with a receding hairline and a sad collection of pulp sci-fi comics cried as he stood alone among tens of thousands of others.

Here I am at thirty-one, seeing The Who for what is probably the actual last time. Pete announces that they’ll play a few songs from Quadrophenia. My heart starts pounding. The whole show so far has been stunning. They are on. This is their farewell to Philadelphia and they want it to be meaningful. They launch into “The Real Me,” another of their sideways coming-of-age stories. And I’m rocking along, making big eyes at my brother as we excitedly bop along to the music of our childhood played by guys who haven’t been teenagers themselves in about five decades. Then Pete starts to picking at the intro to “I’m One.” I’m not excited anymore. I’m not having fun. I am in a room, alone with Pete Townshend, and he is singing this song to me directly. Tears are streaming. This was not at all expected. I mean, I’m an emotional guy and I love a good nostalgia kick. But that’s not what’s happening here. This is a moment based in the right now, not the past. I’m weeping for the thirty-one year old me, who feels like every year is the same and there’s no chance to win and his fingers are too clumsy and his voice is too loud. At fourteen, this song was about the awkwardness of youth. At thirty-one, this song is about a man in the midst of a professional crisis and a weeks-long fight with his wife.

In its vagueness, Pete has written a song that can accompany me throughout my entire life, in all its painful moments. I’m thinking of the passing of my own youth and of the dreams I’ve had to forget in the years between that first concert and this one. And all the thousands of people are singing along, maybe experiencing the same thing. Or maybe “The Kids Are Alright” is the song that does it for them. I glanced at my mom during that song and she had her own tearful reaction. I get that.

I had a similar reaction to “Baba O’Riley.” Is there a more ‘greatest hits’ song in their catalogue? It’s on commercials, a TV show, and the ad for the Peanuts movie for some reason. Nevertheless, it is such a wonder to witness these gods descend to bestow on us the greatest of all rock songs. It just never loses its salt. This song is a purifying, flavoring agent to the life of a Who fan. The synth intro starts, the bass and the drums find their way into the song. Roger Daltrey rips into the vocals with all the vigor of his twenty-five year old self. Then Pete plays the monolithic, mythic, storied chords, reaching into the dim past to send the arms of every audience member into the air. And I start weeping again. What is it about these old rockers that keeps me crying? “Baba O’Riley” was a song that granted power to the teenage me. I’d swing my arms around and I’d be in a place of strength. Maybe it was some amateur version of body language politics. It worked, whatever it was. Hearing them play it and watching old man Pete swing his arms one last time, just reminded me of how powerless I feel these days. It was just too shocking. So I shuddered and I wept.

Shortly before I saw them for the third time, I committed to being a Christian. And I dove hard into that life. Really, I dove in hard to a very specific, dogmatic, cruel version of Christianity. Without going too far into it, I can say that my preoccupation with death found a home in the theology I was studying and subscribing to. In those days, I used to say, “Pete Townshend acknowledged my fears and my pain and he offered to die with me. Jesus offers to die for me.” This reductionist, somewhat trite, formula let me continue to listen to The Who and it let me ground my religion in terms I could relate to when the spirit faded. It was a defense of the music I loved, the music I needed, to an angry God. A decade later, that formula still kind of works for me. Watching Pete flail around on stage a few nights ago engaged me in a positive, vicarious way. He was not speaking for me, but I was free to speak through him. As Pete sang in another Quadrophia song many years ago, “I live your future out, by pounding stages like a clown.”

It’s a gift Pete made, and continues to make, for the losers like me who don’t have an outlet. It’s a gift of expression that meant so much to me as a teenager and apparently means so much to me in my thirties. Rather than trying to defend my love of The Who to an angry God, I can thank a generous God for the gift of this group. I can thank a God that sees my pain and offers to me an expression for it in the form of The Who. My prayers come from my own heart, but sometimes they rhyme.

COMMENTS

2 responses to “The Last Time I’ll See The Who”

Leave a Reply

Kind of brilliant and emotionally powerful, which means – consequential.

I said farewell to The Who in Houston this year. I love them for the same reasons (and the angry, violent, loud shows).