Demythologizing St. Dave

It’s funny thinking about the sheer number of people who count reading David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest the first time as a hinge-point in their lives with the same sort of breathless awe others would fall into when remembering September 11th or Kurt Cobain’s death: funny, in part, because most (appreciators and detractors alike) admit to having no idea how to construe its plot; primarily, though, because it’s so unmistakably a product of the mid-1990s. The wonder of it is how it nevertheless confronts the predicaments of existence in the Twitter age with such eerie and yet comforting prescience.

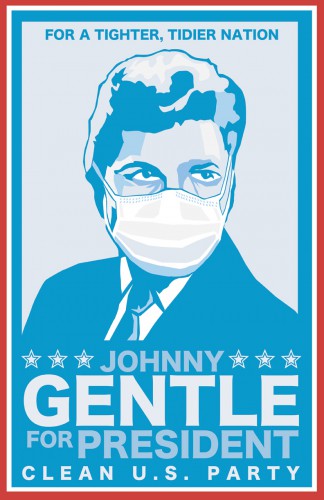

Infinite Jest celebrated its twentieth anniversary this past week, cresting a wave of David Foster Wallace-focused attention set in motion by D.T. Max’s biography Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story and last year’s The End of the Tour. Now a bevy of new publications are surging into the market to help navigate the post-DFW cultural landscape. The very phrase “post-DFW landscape” points out the final reason the novel’s staying power is amusing: no one really anticipated such a 1,079 page (post)postmodern epic of addiction, entertainment, wheelchair-bound terrorists, and tennis finding an initial audience in the first place, much less surviving and thriving two decades beyond its birth. You may not realize it yet, but your words, your thought patterns, your daily juggling acts of meta-awareness of disparate data all have spiraled out from David Foster Wallace’s jousting match with the world. With IJ, Wallace became the founder and precursor of the voice inside your brain you never knew to cite, and we all stand indebted to him for rendering the surreal hypertext links of the postmodern world slightly more coherent.

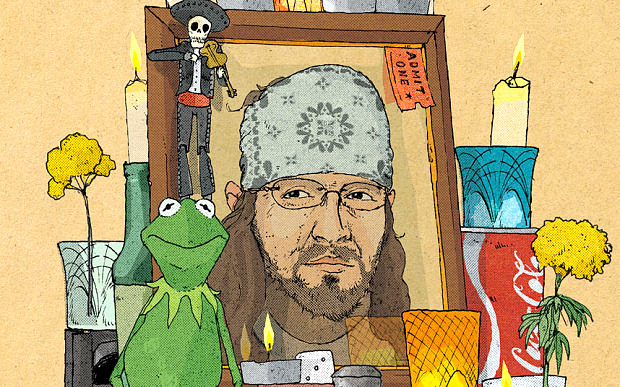

Wallace was a surprise literary torchbearer of the 90s. Prior to Infinite Jest he had won fame and matching wunderkind status for his novel The Broom of the System (a book which began as his second undergraduate thesis at Amherst College) but had seemed to fail of his promise when he bottomed out under the strain of addiction and chronic anxiety at 28. Yeah: 28. (What have you been working on lately?) IJ was a tangible, readable instantiation of his recovery, not to mention a monumental progression in style and substance from Broom. IJ earned him Literary Voice of a Generation accolades and a legion of wounded, sincerity-starved appreciators who have peremptorily canonized him as St. Dave.

Wallace was a surprise literary torchbearer of the 90s. Prior to Infinite Jest he had won fame and matching wunderkind status for his novel The Broom of the System (a book which began as his second undergraduate thesis at Amherst College) but had seemed to fail of his promise when he bottomed out under the strain of addiction and chronic anxiety at 28. Yeah: 28. (What have you been working on lately?) IJ was a tangible, readable instantiation of his recovery, not to mention a monumental progression in style and substance from Broom. IJ earned him Literary Voice of a Generation accolades and a legion of wounded, sincerity-starved appreciators who have peremptorily canonized him as St. Dave.

Wallace ensorcelled readers with his blend of ultra-articulate wit, hyperaware descriptiveness, and an aching, quasi-spiritual plaintiveness which yearned for something the world and its commodified absurdities could not fulfill. Many writers make a pretense of rejecting the anodyne comforts of their era, but what was so refreshing about Wallace was the honesty and vulnerability with which he insisted that he was just as swept up within those comforts as were the targets of his fiction and his essays. He examined himself and his world to an exhausting, exasperating extent in his search for satisfaction, and his failure to lay hold of it decisively gave birth to his legend, that of a thinker so pure, so guileless and stalwart he couldn’t withstand the vicious emptiness of the contemporary world.

But how do we speak well of a secular saint? By slicing through the mystical accretion disc that has obscured his fundamental humanity (viz. the St. Dave persona) and refusing to sand down the jagged, splintery edges of his life. By situating both Wallace and Infinite Jest in the life of our culture we see more clearly than ever that he diagnosed the ills of postmodernity with such fathomless insight precisely because he embodied those ills in himself. More importantly by far, however, he signaled to us escape hatches within the postmodern prison, entries into something authentic, spacious, and of much older pedigree.

The Postmartyr Condition

Right away, then, we have to address something: part of the aura emanating off of Infinite Jest is really the reflection of DFW’s retroactive halo. The novel is powerful in itself, and yet its pathos is greater than the sum of fractal parts precisely because of St. Dave’s canonization. The shadow of St. Dave illuminates the work and amplifies its potency, nourishing in turn the legend of St. Dave and separating him from the rest of us mere mortals. Isn’t it odd, though, how we lavish such frenzied adoration upon figures like Wallace for their “uniqueness” and “singularity” and then feel a compulsive need to find a precursor to share their pedestal with? We’re so docetic at heart that we see helpful words as otherworldly and ascribe impeccability to their speaker. We take the gift of heroes but corrupt the gift by crafting idols in their own image, particularly with the heroes we have lost, whom we install as placebo Christs.

Right away, then, we have to address something: part of the aura emanating off of Infinite Jest is really the reflection of DFW’s retroactive halo. The novel is powerful in itself, and yet its pathos is greater than the sum of fractal parts precisely because of St. Dave’s canonization. The shadow of St. Dave illuminates the work and amplifies its potency, nourishing in turn the legend of St. Dave and separating him from the rest of us mere mortals. Isn’t it odd, though, how we lavish such frenzied adoration upon figures like Wallace for their “uniqueness” and “singularity” and then feel a compulsive need to find a precursor to share their pedestal with? We’re so docetic at heart that we see helpful words as otherworldly and ascribe impeccability to their speaker. We take the gift of heroes but corrupt the gift by crafting idols in their own image, particularly with the heroes we have lost, whom we install as placebo Christs.

DFW is obviously no exception. Comparisons to Kurt Cobain are often thrown around, but apart from the rabid devotion of their acolytes and the long hair, there just isn’t much to the parallel. Wallace’s literacy places him more in the company of Darby Crash and Ian Curtis, if anything. Even here, however, the divide is deep and wide because both Crash and Curtis were poets of unremitting hopelessness. Darby Crash danced, desperately, deliriously dissipated, around the cenotaph of traditional American certainties, both terrified and elated by the freedom of nihilism. Ian Curtis convulsed through the icy wastes of post-industrial emptiness. While Wallace was no stranger to despair, his work is cherished precisely because his depictions of humanity at its most dreadful and pathetic were the very sites from which geysers of grace and hope irrupted to open up new possibilities.

Protestant readers are more likely to baptize Wallace as a sort of postmodern William Cowper. I know I have. We derive such comfort from Wallace’s work we can try to dim the lights and cross our eyes to see him as a bandana’ed Cowper, ennobling our miseries and sublimating them into worship. Above all, we see in both a near-impossiblity to straddle the space between what is and what ought to be, between, that is, the already and the not-yet. Cowper, though a believer, struggled to believe he could be loved by a good God. And Wallace, however Christian his hope may or may not have been, feared the not-yet might never be, and his gigantic self-awareness tortured him.

Wallace was dissatisfied, and his dissatisfaction stoked his craft. Like Cobain, Crash, and Curtis, Wallace combated the emptiness he inherited with the solvent of words. Unlike them, Wallace’s words were more than acids symbolically dissolving the awful and real: his words, loaned from and informed by other movements of spirit, were a detergent. They cleansed the conscience and made old words and ways of being usable again.

The legend of St. Dave is fed by Wallace’s real attempt to resist the habits and products that fueled that emptiness. The patterns of American escapism shaped his consciousness, his methods of coping, and ultimately the structure and content of his work as he began to recognize the anti-humanistic impulses of his and our inheritance.

The legend of St. Dave is fed by Wallace’s real attempt to resist the habits and products that fueled that emptiness. The patterns of American escapism shaped his consciousness, his methods of coping, and ultimately the structure and content of his work as he began to recognize the anti-humanistic impulses of his and our inheritance.

By the time he began work on Infinite Jest a crucial realization had dawned: all the anesthetics America clamored to make available to him were “solutions” to the starving of the human spirit that only amplified the ache of the human heart for a meaning it was made for but now eluded its grasp. Wallace’s chronic anxiety was systemic, he realized, and the prescriptions for it at our disposal (TV, sex, drugs, etc.) relieved that anxiety to an extent (just enough to guarantee our patronage) but also imprisoned us within vicious feedback loops of emptiness that seemed to destabilize even the most self-evident realities.

Wallace was dismayed to find artists contributing to that abyss of meaning with ironic unconcern. Having narrowly survived the emptiness of this way of life himself he demanded the return of redemptive possibilities to literature. Or did that not matter anymore? Could words no longer serve such purposes? Wallace was about to curve his own training in on itself.

The After-Word and the Capitalized Word

As a novelist and as a thinker, Wallace only makes sense at the tail end of an involuted, counterintuitive movement in literary theory and philosophy that over the course of the twentieth century has threatened to disintegrate the humanities from within. If that sounds melodramatic, take a few minutes to examine how many papers and seminars over the last forty years have addressed “the crisis of the humanities.” The crisis is nothing less than the death of the author, and behind that, the silencing of the Author.

It was once generally accepted that authors spoke through their texts, that texts preserved the voice of their authors. On the scale of the everyday we interacted with one another counting on the fact that our words could and would convey meaning to others. Underlying this was the assumption the eternal Word underwrote our words and preserved meaning in what we said, what we experienced, and what we read. Under the intense criticism of various deconstructive theories, though, the fixedness of meaning came to be seen as parochial. Obsolete. Meaning didn’t reside in words–words were merely the instruments of coercion and of self-manufacture.

The deconstructive poetics Wallace encountered pictured a sort of Freudian antagonistic struggle occurring in the phenomenon of reading: in Roland Barthes’ estimation, the author must die for the reader to live. That is, the author mustn’t be allowed to impose anything upon the reader that would limit the reader’s constructive interaction with the text. Thinkers such as Foucault and Derrida followed suit: the voice of the author would circumscribe the reader’s freedom to not only engage the free play of signs, but to actually become a self in so doing.

Instead of opening a vast new world of freedom, however, this death of the authorial tyrant, wed to the Romantic ideal of the creative individual, opened the door to a new despot: the death-dealing constriction of self-creation, the idea that my validity as a person is bound up with my ingenuity as an interpreter. Ours is a time eyeball-deep in this agonizing anxiety, trying in vain to resist the pressure of limits, boundaries, and finitudes from without with the osmotic pressure of identity construction. It’s exhausting. But it’s the only option available in the absence of the Author-God: the postmodern patricide ruled anything else out.

This crisis of the deconstruction of meaning is what George Steiner calls the After-word, and it characterizes the hopelessness of our contemporary scene. But its formal features were still clever enough and they could be appropriated by the culture industry. The crank-turners had been unleashed to perform the same function as TV and the other narcotics Wallace had depended on. The Word had been made lower case just to end up capitalized like every other commodity.

Enter DFW–but not immediately on the side of the angels. Wallace’s discovery of avant garde fiction from authors such as Donald Barthelme and Thomas Pynchon ignited his desire to write. Postmodern fiction fractured the shiny surface of literature to render visible the mechanics of its illusions. It claimed that words only papered over the disorder within the self and the world, that structure was an artifice masking an agenda. Implicitly it claimed that the only integrity to be had was in owning up to this artificiality of meaning and integrity, and many of its purveyors seemed to incarnate that ethos.

Enter DFW–but not immediately on the side of the angels. Wallace’s discovery of avant garde fiction from authors such as Donald Barthelme and Thomas Pynchon ignited his desire to write. Postmodern fiction fractured the shiny surface of literature to render visible the mechanics of its illusions. It claimed that words only papered over the disorder within the self and the world, that structure was an artifice masking an agenda. Implicitly it claimed that the only integrity to be had was in owning up to this artificiality of meaning and integrity, and many of its purveyors seemed to incarnate that ethos.

Somehow, when this brand of clever-than-thou lit collided with Wallace’s bundle of brains and instabilities, a writer was conceived, albeit a very different writer from the author of Infinite Jest. This David Foster Wallace embraced the ironically distant, self-referential wordplay which corresponded so closely to his own inner fragmentation. Broom exemplified this, as did many of the stories making up Girl with Curious Hair. Girl’s final story, “Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way,” however, put these devices to a new use: strangling irony with its own tentacles. With “Westward,” in particular, Wallace tried to punch a hole through the textual universe he inherited with an antimatter blast of pure negation, hoping the smoke would clear and reveal, beyond the rubble, a literary world of sincerity and compassion. He had begun to turn on a movement that prided itself on the smug detachment of remembering fiction was “only” stories.

Wallace at this time had moved beyond the younger Wittgenstein of his undergrad days and absorbed the mature Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations. PI eviscerated his earlier work which painted such a drab, positivist portrait of the relation between our language and the world. PI located words’ meanings in shared, communal practices, tradition, and public criteria of fittingness. In all this, Wittgenstein assumed a word-to-world fit: not perfect picture correspondence, perhaps, but real compatibility between language and life as real people together navigate and make use of that shared world. In his book Real Presences, George Steiner calls this the “covenant between the word and world” and traces the splintering of reality under postmodernism along the contours of the radical doubt thrown upon language’s capacities, doubts which (this is crucial) make their war upon meaning through language.

“New persuasive words” would be needed to rehabilitate the present, new words apprenticed by older, degraded ones (T. Wilder). Even more than that, what would be needed was a subject who could exist outside of language and yet possess a being so word-shaped and word-consistent that all speech could be transparent and coherent to him, a subject who could bridge the divide between inner and outer, upper and lower, and enter into language from outside to inhabit it from within. What Wallace needed was Christ, the Word made flesh.

Part 2 coming soon!

COMMENTS

3 responses to “The World Within the Fracture: 20 Years of Infinite Jest, Pt. 1”

Leave a Reply

This is so wonderful, Ian. Thank you for sharing it with us. Can’t wait to read part 2.

“While Wallace was no stranger to despair, his work is cherished precisely because his depictions of humanity at its most dreadful and pathetic were the very sites from which geysers of grace and hope irrupted to open up new possibilities.” Love that. Great post!