Welcome to the third installment of act two of author Ted Scofield’s series on everybody else’s biggest problem but your own. If you missed one or more of the previous installments, you can find them here.

In Act One of this greed epic, we determined that as a culture we cannot define the term and, although we’re quick to see greed in others, we refuse to see it in ourselves.

In Act Two we’re examining why we cannot define and admit to greed. Last time we discovered that, right or wrong, in our society money is a proxy for intelligence, so accumulating lots of it can’t be greed, at least not when we do it.

Today we’ll explore a third answer to the Why? question, the fact that the “American Dream” is a quantifiable, material dream, measured by how much money, and the stuff money can buy, we possess. Few of us articulate the American Dream in spiritual or intellectual terms, and if we pretend otherwise, we’d prefer to pray, meditate and yoga our way to enlightened nirvana with a Benz parked in our mansion’s garage.

*****

Noah Webster spent a lifetime devoted to distinguishing American English from the Queen’s English, and Merriam-Webster is the quintessential American dictionary:

Definition of American dream: an American social ideal that stresses egalitarianism and especially material prosperity; also: the prosperity or life that is the realization of this ideal.

Definition of American dream: an American social ideal that stresses egalitarianism and especially material prosperity; also: the prosperity or life that is the realization of this ideal.

Few dispute the accuracy of Webster’s definition, but over the past several decades, according to most commentators, we have dropped the interest in egalitarianism to focus almost exclusively on material prosperity.

In 1973, Dr. John E. Nestler wrote, “Whereas the American Dream was once equated with certain principles of freedom, it is now equated with things. The American Dream has undergone a metamorphosis from principles to materialism.” Philosophy professor Richard Kortum argues “material prosperity has always lain at the heart of the American Dream.”

Fascinating historical contrasts are legion. In ancient Greece, for example, Aristotle’s ideal was eudaemonia, human flourishing characterized by a life lived ethically, guided by reason and dedicated to pursuing personal virtue.

Our Founding Fathers looked to Greece for democratic ideals, but that’s about it. In colonial America, the American Dream was conceived. Some might say it was an inevitable element of Manifest Destiny, a cornerstone of American exceptionalism. Others might say it launched Kafka’s Die Verwandlung, an odious transformation from a people full of principle to a nation of hollow consumers.

In 1774, our First Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Colonial Rights, which argued the colonists were “entitled to life, liberty, and property.” Two years later, for a variety of reasons, Thomas Jefferson famously changed the words to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Professor Carol V. Hamilton commented in 2008:

For many Americans, Jefferson might just as well have left “property” in place. To them the pursuit of happiness means no more than the pursuit of wealth and status as embodied in a McMansion, a Lexus, and membership in a country club.

And, despite data to the contrary, how do we Americans pursue happiness? We buy it, of course!

If that reality is not obvious to you, think about it for a moment. Rarely does “livin’ the dream” refer to a studio apartment, a bus pass and ramen noodles. Livin’ the dream is something exorbitant, distinctly not average, an Instagram moment or, better yet, a LinkedIn life of “having it all.” And it’s deeply rooted in the American psyche.

If that reality is not obvious to you, think about it for a moment. Rarely does “livin’ the dream” refer to a studio apartment, a bus pass and ramen noodles. Livin’ the dream is something exorbitant, distinctly not average, an Instagram moment or, better yet, a LinkedIn life of “having it all.” And it’s deeply rooted in the American psyche.

In the 19th century, Horatio Alger’s eternally optimistic stories epitomized the American Dream. His young heroes struggled against poverty and adversity to achieve wealth and acclaim. Despite what are now described as “cringe-worthy” plots and dialogue, Alger’s rags-to-riches tales have sold tens of millions of copies and inspired countless uniquely American characters, from Rocky’s titular pugilist, who literally fought his way from rags to riches, to Pretty Woman’s Vivian Ward, who had a slightly different set of skills.

In 1925’s The Great Gatsby, Jay is convinced he can buy happiness, found only in the love of a woman, Daisy. He says to Nick, “Her voice is full of money,” to which Nick replies:

That was it. I’d never understood before. It was full of money — that was the inexhaustible charm that rose and fell in it, the jingle of it, the cymbals’ song of it…high in a white palace the king’s daughter, the golden girl….

Jay, of course, is never able to buy his golden girl, unfaithful old money trumping devoted new. He is shot to death in a tragic misunderstanding. Few of his “friends” bother to attend his funeral.

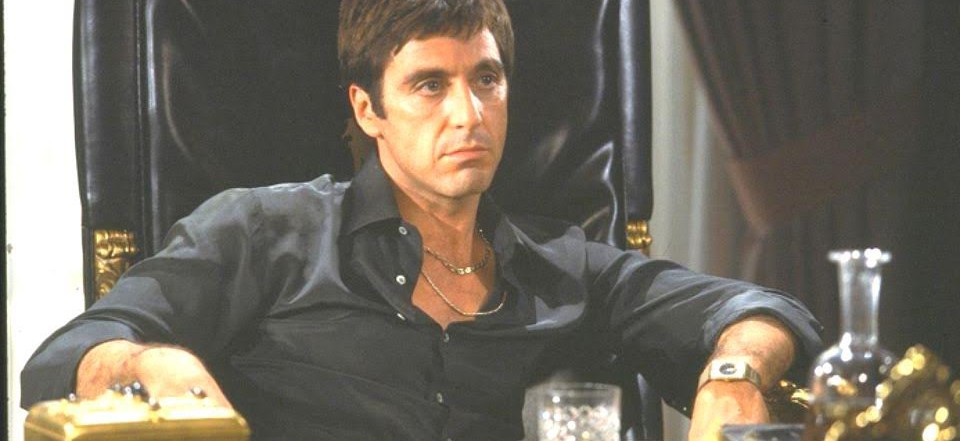

A more recent pop culture touchstone cuts to the chase. Penniless refugee Tony Montana arrives in America with one thing on his mind: The American Dream. He declares: “In this country, you gotta make the money first. Then when you get the money, you get the power. Then when you get the power, then you get the women.” In Brian de Palma’s Scarface, Tony gets all three and is shot dead by a rival drug lord. His eviscerated body falls into a fountain, in front of a statue that reads “The World is Yours.” Like his dream, Tony Montana is, quite literally, hollow.

Despite the cautionary conclusions of Gatsby and Scarface, Horatio Alger’s silly stories have won out. Why? Because they are fundamentally optimistic. Professor Kortum explains: “The idea is that even if you were ‘dirt poor’ to begin with, if you worked hard enough and followed the rules, you could eventually achieve just about anything you wanted.” Horatio delivers Daisy and the Dream but without the spiritual and physical disembowelment. Horatio also articulates the path to the money that buys the Dream: The American Work Ethic.

Carl Cederstrom, an author and professor of organization studies, recently wrote in The New York Times, “unlike the work-shy Greeks of antiquity, we are assumed to find happiness through work and by being productive.” The implicit assumption in Cederstrom’s words, and explicit lesson of rags-to-riches tales, is that hard work leads directly to material success, our default proxy for happiness, and material success is a result of hard work. Data suggest we accept this foundational equation.

In 2012 Pew Research asked 2,508 adults if rich people are more likely or less likely than the average person to be hardworking. Forty-two percent (42%) of respondents said rich people are more likely to be hardworking than the average person. Only 24% said less likely.

In 2004, four years before the Great Recession, Professor Kortum wrote that a common perception “is that poverty is a sign of laziness…I hear it too often from the mouths of junior students at my own university: ‘Poor people are poor because they’re just too lazy to get a job.’”

Carl Cederstrom elaborates:

Carl Cederstrom elaborates:

When no sin is greater than being unemployed and no vice more despised than laziness, happiness comes only to those who work hard, have the right attitude and struggle for self-improvement…It is drummed into the poor and unemployed who are led to believe that their misfortunes are symptoms of their inferior attitudes and inability to take ownership of their lives.

In a thriving economy, coupled with our nation’s extensive historical and cultural underpinnings, one might understand the thinking.

So what do students say today, when America is mired in a stagnant economy and decent jobs are few and far between? The headline, from Harvard University, says it all: “Half of Young Americans Believe the American Dream is Dead for Them.”

It makes sick sense, doesn’t it? When hard work is reduced to minimum wage, and money hard to come by, the Dream is dead. Half of Americans age 18 to 29 say this is so.

Why? Because the American Dream is a material dream, paid for with money earned by the unforgiving American Work Ethic. And what is proof of our hard work? What is the measure of our Ethic, the fulfillment of our Dream? I know the answer. You know the answer. We want “livin’ the dream” to be more than our carefully curated Facebook photos. We want a lifetime of liberty and property. We want Jay Gatsby’s Rolls Royce and Tony Montana’s waterfront mansion. And it’s gonna cost us more than our hard-earned money. It just might cost us our souls. But that is the American Dream and we will not, we cannot, label it “greed.”

COMMENTS

2 responses to “Everybody Else’s Biggest Problem: Livin’ the Dream”

Leave a Reply

Thank you Mockingbird & Mr. Scofield for another thought-provoking post on a tough topic. I love tragically true sentence: “Few of us articulate the American Dream in spiritual or intellectual terms, and if we pretend otherwise, we’d prefer to pray, meditate and yoga our way to enlightened nirvana with a Benz parked in our mansion’s garage.”

Also I just saw this article with the headline: “Obama has nearly killed the American Dream. No wonder voters are turning to fantasy politics“. The article makes a similar point, that if the American economy is weak, then the American dream is dead because it must be bought with money. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/us-election/12153559/Donald-Trump-and-Bernie-Sanders-are-offering-fantasy-politics-to-fix-Obamas-America.html

Looking forward to the next installment!

In the words of the legendary Siskel & Ebert: “Two thumbs up, way up”