Well, the unthinkable has happened. Axl and Slash have buried the hatchet and are confirmed to be playing a headlining set (with Duff, possibly others) at Coachella this year. True to my word, to celebrate the momentous news, I’m posting the full Guns n Roses chapter of A Mess of Help: From the Crucified Soul of Rock n Roll. Portions of it appeared years ago in various forms on this site, but what you’ll find below was completely rewritten and is about three times longer – thus the Super Deluxe descriptor. Hope you have a fraction of the fun reading it that I had writing it.

Intrigued, excited, and more than a little scared was how I felt when I first encountered the rock n’ roll tsunami known as Axl Rose. It was the late 1980s, and Guns N’ Roses’ Appetite for Destruction was just starting to take over the radio. The few (illicit) glimpses of the band I had caught on MTV confirmed that they looked as dangerous as they sounded. Axl had yet to stop wearing eye shadow or teasing his hair out. Slash’s face was still shrouded in mystery. The rest of the guys seemed like they could barely stand.

My musical interests up to that point had been limited primarily to the “B” section of my father’s record collection, and I remember thinking that “Sweet Child O’ Mine” sounded a bit like The Beatles. I asked my guitar teacher to help me learn how to play the intro, but he declined. That’s about as far as it went.

Then came Lies, my true entry point. Looking back, the ‘double EP’ was a heat-seeking missile aimed at eleven year old boys: joke headlines on the cover mythologizing the band’s debauched lifestyle, curse words galore, and an insert of a topless woman, perfectly positioned to be hidden from moms everywhere.[1] The songs were pretty good, too. Lighter than Appetite, but laden with hooks: “Patience” marked GNR’s first proper attempt at a ballad, complete with killer coda and ueber-salacious video. “Used to Love Her” was stupid-funny in a way that pubescent males can’t resist (“…but I had to kill her”), and the controversial, epithet-spewing “One in a Million” provided the requisite sense of foreboding. Lies was something to keep from adults, something that was yours and yours alone.

Then came Lies, my true entry point. Looking back, the ‘double EP’ was a heat-seeking missile aimed at eleven year old boys: joke headlines on the cover mythologizing the band’s debauched lifestyle, curse words galore, and an insert of a topless woman, perfectly positioned to be hidden from moms everywhere.[1] The songs were pretty good, too. Lighter than Appetite, but laden with hooks: “Patience” marked GNR’s first proper attempt at a ballad, complete with killer coda and ueber-salacious video. “Used to Love Her” was stupid-funny in a way that pubescent males can’t resist (“…but I had to kill her”), and the controversial, epithet-spewing “One in a Million” provided the requisite sense of foreboding. Lies was something to keep from adults, something that was yours and yours alone.

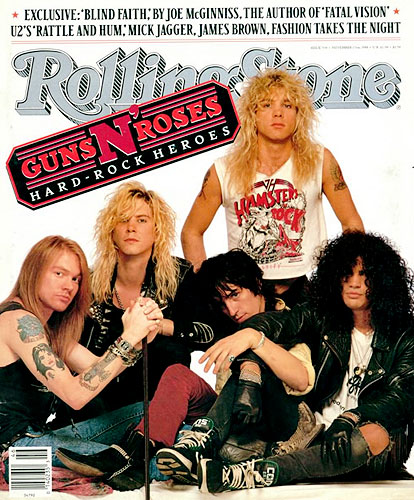

Guns N’ Roses are considered by many to be the last truly great rock n’ roll band, and for good reason.[2] Like many of those who came before them, at their center lay a charismatic duo: Axl, the combustible, larger than life frontman, and Slash, the enigmatic lead guitarist. They arrived on the scene like a couple of superheroes. They wore superhero clothes, had superhero names, and harbored superhero ambitions. If the videos in which they appeared were any indication, they even had superhero abilities. Axl swam with dolphins and jumped into wedding cakes. Slash could walk on water while wailing on guitar (“Estranged”). Again, the whole thing could not have been more appealing to suburban male tweens.

As memorable as Slash’s solos were—his work on “November Rain” remains a high-water mark of the form—it was combative, unpredictable Axl that captured my attention. He had my admiration. He had my devotion. He even had my compassion. And unlike a lot of the things I was interested in when I was eleven, he still has it. I have never stopped listening to his music. In fact, as juvenile as some of it may have initially seemed, over the years I’ve only found more and more to love.

I remember being confused and slightly heartbroken when one of the middle-school friends with whom I had memorized the words to “Get in the Ring” (those familiar with the song will know which part) came home from a youth-group retreat and decided to throw away all his GNR. His youth pastor had apparently objected to the band’s degenerate image and profligate swearing. I couldn’t have told you why at the time—the facts certainly weren’t on my side—but in my gut I knew it was a shortsighted move. He was missing something. It took my own conversion many years later to figure out what it was.

I remember being confused and slightly heartbroken when one of the middle-school friends with whom I had memorized the words to “Get in the Ring” (those familiar with the song will know which part) came home from a youth-group retreat and decided to throw away all his GNR. His youth pastor had apparently objected to the band’s degenerate image and profligate swearing. I couldn’t have told you why at the time—the facts certainly weren’t on my side—but in my gut I knew it was a shortsighted move. He was missing something. It took my own conversion many years later to figure out what it was.

Here goes: There are few more compelling illustrations of the dynamic between judgment and love than the life and music of William Axl Rose. This dynamic is not of secondary importance; it lies at the very heart of our relationships with both other people and God. Even the name of Axl’s band echoed these themes, the gun being a symbol of control and the rose one of affection. In theological terms, one might say that the crushing power of the law (the omnipresent “oughts” of life), in both its sacred and secular forms, finds unfortunate yet serious traction in the saga of Guns N’ Roses, with Axl Rose as its main object (and part of its subject). Yet his story also touches on the inspiring nature of love, the beauty and pain of our inner divisions, and, perhaps, the unshakeable power of the cross.

Things Get Worse Here Every Day

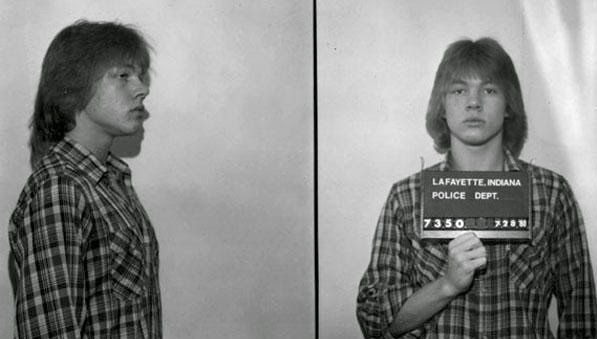

William Axl Rose grew up in Lafayette, Indiana, the adopted son of a Pentecostal preacher who inflicted upon him a truly merciless form of Christianity, if it can even be called such. All rules and no grace, the sort of Bible church situation which majored in behavior control and church attendance, attempting to keep the lid on the human sinfulness so tightly that it caused vicious splits in the lives of its followers. Axl once described it in the following, assumedly exaggerated terms (but still):

“My particular church was filled with self-righteous hypocrites who were child abusers and child molesters. These were people who’d been damaged in their own childhoods and in their lives. These were people who were finding God but still living with their damage and inflicting it upon their children. I had to go to church anywhere from three to eight times a week. I even taught Bible school while I was being beaten and my sister was being molested. We’d have televisions one week, then my step-dad would throw them out because they were satanic. I wasn’t allowed to listen to music. Women were evil. Everything was evil.”[3]

Even if we’re allowing Axl some room for overstatement, it is probably not a stretch to describe him as the product of a highly dubious kind of religion: bootcamp American pietism, marked by a God-helps-those-who-help-themselves theology that is ardently practiced to the point of cruelty, completely at odds with its founder.[4] The distance young Axl had to travel to escape, both geographically and in his lifestyle, probably correlates pretty closely with the toxicity of his circumstances in Lafayette. Axl’s upbringing, and his response to it, is not uncommon. Strict parents often produce rebellious kids, and rebellious kids often run away. Yet there is only one Axl Rose, and his story only begins there.

As soon as he could, and after finding out that the preacher in question was not in fact his biological father, Axl hopped a bus to Los Angeles, following his friend Izzy Stradlin. When he arrived in “the jungle” of LA, he proceeded to dive headfirst into one of the most decadent scenes in the country. Once in LA, he began honing the skill he had, ironically enough, learned in church, singing in bands and eventually finding his way to the rest of what would become Guns N’ Roses. This group of fellow outcasts shared not only his dereliction, but (some of) his talent. Together, they would experience heretofore unknown degrees of acceptance, affirmation, inspiration and—let’s face it—love.

Freed of his constraints and surrounded by what might loosely be called a ‘supportive’ environment, the creativity exploded. Appetite for Destruction is one of those rare rock n’ roll collaborations in which ego didn’t play a central role. The five band members lived together in a single room and wrote the entire thing there—together. All of the songwriting credits were split between the five members, virtually unheard-of in these situations.

The songwriting and musicianship on Appetite are uniformly glorious. A perfect concoction of influences, intricately arranged, bursting with both melody and aggression, played by a band whose chemistry was telepathic—the guitarists especially—all of it filtered through Axl’s off-the-charts charisma. The band seemed to emerge fully-formed from the opening howl of “Welcome to the Jungle”, not letting up on the energy until the final notes of “Rocket Queen”. More than a quarter-century later, Appetite barrages the listener with line after classic line, riff after classic riff, a surprise around every corner.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C7i6sm11MPg

Take their classic “Paradise City” for example. At nearly seven minutes, it is the longest song on Appetite, as well as the one which covers the most musical ground. Listen closely and you’ll hear a set of shifting dynamics woven together with remarkable precision and feeling, with each section building on the one before it. The song opens with a pretty, arpeggiated chord progression and instantly recognizable drum pattern before a whistle sounds and the main, almost funky riff grabs hold. As Axl finishes spitting each of the verses, the guitars drop out for a half-measure before the band falls into the anthemic chorus, and then again before that ascending riff starts chugging again. They wait a full three and a half minutes to segue into the crooning bridge (“so faaaar away”), and then, just when you think it’s over, they play the whole thing double-time, getting faster and faster until crashing into an exhausted finish. It’s not just the musicality on display that takes the breath away but the confidence. This was their first album.

In contrast to the hairband clichés that ruled the Sunset Strip at the time, the lyrics on Appetite have dimension to spare. In turns biting and poetic, never dumb, and occasionally flashing some of the intellectual bent Axl would showcase on Use Your Illusion, the record is a stunning portrait of human conflictedness. Unbelievable rage one minute (“Out To Get Me”) is followed by real sweetness the next (“Think About You”). Attitudes toward women are nothing short of schizophrenic, ranging from unlistenable misogyny (“My Michelle”) to worshipful adoration (“Sweet Child O’ Mine”), sometimes in the same song (“Rocket Queen”). Images of Axl as a vulnerable child, praying for the thunder and rain to pass him by, are juxtaposed with a grown man preying on the vulnerable newcomer in his city (“I wanna watch you bleed”).

A s the title indicates, the band’s relationship with its own indulgences is one of the main themes of Appetite. Axl praises the “Anything Goes” ethos of mid-80s Los Angeles—and his dominance of it—but later confesses how “nothing seems to please me”. Substances play a prominent role throughout, with the singer rhapsodizing about riding on the “Night train, loaded like a freight train, flying liking an airplane” before describing the perils of heroin addiction on “Mr. Brownstone” (who won’t leave them alone). The latter track is one of several masterpieces on the record. What initially sounds like a glorification of the drugged-out rock n’ roll lifestyle becomes a confession of powerlessness (“I used to do a little but a little wouldn’t do it, so a little got more and more”) and regret (“I wish I’d known better”). The moral element is unexpected, to say the least.

s the title indicates, the band’s relationship with its own indulgences is one of the main themes of Appetite. Axl praises the “Anything Goes” ethos of mid-80s Los Angeles—and his dominance of it—but later confesses how “nothing seems to please me”. Substances play a prominent role throughout, with the singer rhapsodizing about riding on the “Night train, loaded like a freight train, flying liking an airplane” before describing the perils of heroin addiction on “Mr. Brownstone” (who won’t leave them alone). The latter track is one of several masterpieces on the record. What initially sounds like a glorification of the drugged-out rock n’ roll lifestyle becomes a confession of powerlessness (“I used to do a little but a little wouldn’t do it, so a little got more and more”) and regret (“I wish I’d known better”). The moral element is unexpected, to say the least.

As harrowing as some of the subject matter may be, the overall energy of the record is undeniably invigorating. To this day, Appetite never fails to get a party started. Furthermore, the very fact that Axl did not suppress his inner turmoil should be indicative of the relative freedom he was feeling during its creation. Confession almost always entails some degree of safety and prior acceptance, otherwise we keep things hidden. Then again, perhaps he simply couldn’t keep it in any longer.

While there is no explicitly religious content on Appetite—beyond the cross on the cover, that is!—there is plenty of religious subtext. The world is portrayed as a malevolent jungle, deeply regressive in nature (“things get worse here every day”), equally depraved and depraving, bringing the its denizens to their sha-na-na-na-na-na-na-knees, where all they can do is yearn for deliverance, aka Paradise City, aka HOME. Axl could sell these wildly divergent themes because (1) they were true to life, and (2) he possessed an absurdly dexterous voice.

The response to Appetite was rapturous, and never to be repeated by anyone, ever. It remains the top-selling debut record of all time. The artistry leapt out of the speakers, casting a pall on the many pretenders who made up the LA hair-metal scene, and fixing itself in the hearts and minds (and ears) of several generations to come. More than twenty-five years later, you still can hardly attend a professional sports game without hearing the opening riff to “Welcome to the Jungle” more times than you can count.

The response to Appetite was rapturous, and never to be repeated by anyone, ever. It remains the top-selling debut record of all time. The artistry leapt out of the speakers, casting a pall on the many pretenders who made up the LA hair-metal scene, and fixing itself in the hearts and minds (and ears) of several generations to come. More than twenty-five years later, you still can hardly attend a professional sports game without hearing the opening riff to “Welcome to the Jungle” more times than you can count.

As notoriously hedonistic as the group’s lifestyle became, the strange fellowship of early Guns N’ Roses produced enormous fruit. In his band of misfits and the glorious racket they made together, Axl had found the encouragement that the church had denied him. Even the record’s most misanthropic moments are delivered with exuberance, and nary a trace of the self-consciousness that would mark future projects. Considering the poisonous atmosphere from which Axl had escaped, we might be forgiven for hearing Appetite for Destruction as a celebration of his liberation, the sound of acceptance triumphing over criticism, grace over law. If you want to get cute, you might say that where ‘instruction’ had failed, ‘destruction’ flourished…!

Everything Was Roses (When We Held Onto the Guns)

“I just want to bury Appetite. I don’t want to live my life through that one album. I have to bury it, and do something new.” —Axl Rose

What does one do for an encore? If you’re Axl Rose, you take an extreme situation and make it even more so. He knew full well that Appetite for Destruction could come to define them—a gold standard that would loom over everything else GNR did, a measure by which all their subsequent efforts would be judged, inevitably falling short. To call it the fulfillment of all musical righteousness wouldn’t be (too) far-fetched. Which means that if Appetite was born out of freedom (from Lafayette, the church, authorities of all kinds, etc.), then its success reintroduced the albatross of judgment. The double-album follow-up Use Your Illusion would prove one of rock’s most fascinating documents of a band’s struggle with the Law of Success.

Like anyone finely attuned to the devastating power of judgment, Axl was dead-set on escaping it. The challenge this time, however, was more than circumstantial. There was no Lafayette to leave behind. The pressures were internal as much as external, maybe more so. That is, the considerable expectations of their record company and fanbase were matched, if not dwarfed, by the band’s own desire to top themselves, to evolve, to transform Appetite into a prelude to something bigger.

The cover of the “Don’t Cry” single

So, backed into a corner by the magnitude of their triumph, Axl reacted in characteristically exaggerated form: he lobbed what amounted to an artistic nuclear bomb—or perhaps more appropriately, a middle finger—at all of what Appetite for Destruction represented. Sadly, the law contains a double-bind: rebelling against a standard is no different from conforming to one.

The environment in which Use Your Illusion was conceived diverged substantially from that of their previous albums. Like oh-so-many other Behind The Music subjects, the potent cocktail of money, fame, and substances inflated egos and ignited tempers, leading all involved to make their claims of credit and fight over pieces of a pie that simply wasn’t conceived as such before.[5] Of course, competition can also create the kind of friction that makes for good music, and perhaps our heroes had not quite reached the tipping point. That much of the competition was taking place inside Axl’s mind should come as no surprise.

Read any of the memoirs or articles about this period of GNR, and you’ll encounter the same term used to describe Axl, namely, “control freak”. The singer apparently began to assert his influence over everyone around him, from crew members to journalists to band members to girlfriends, in a fashion that doesn’t sound terribly dissimilar to that of his step-father (and the members of his church). Onlookers report that Axl became increasingly obsessed with managing his image and appearance. No potshots, no weakness, no transgression allowed—the illusion of complete dominance must be upheld at any cost! Needless to say, as control began to subvert collaboration, and self-interest came to dictate the proceedings, the band’s creativity suffered.

Anyone familiar with rock n’ roll or literature or art more generally is familiar with the curious commandment that artists must always ‘progress’, or improve with each new work. Indeed, one of the worst criticisms you can lodge with a creative artist is that they’re repeating themselves or not trudging fresh territory. GNR were certainly familiar with this demand. It all but ensured that the energy of Appetite be lost on the follow-up, that spontaneity would give way to perfectionism and its unwelcome friend, paralysis. Perhaps, then, it is no surprise that the process of recording Use Your Illusion took a long time and an ungodly amount of money.[6] As Axl put it at the time, with trademark humility:

“We didn’t just throw something together to be rock stars. We wanted to put something together that meant everything to us… We’re competing with rock legends now, and we’re honored to be in that position. We want to define ourselves. Appetite was a cornerstone, a place to start. It was like, ‘Here’s our stand,’ and we just put a stake in the ground. Now we’re going to build something.”

Given the pressure they were imposing on themselves, it speaks to Axl’s singular determination (and the depth of his anger) that the record was ever completed.

Anxious to best themselves, the guys moved in all directions at once, letting loose a truly manic collection of thirty songs—two discs/volumes, released on the same day, unheard-of before or since. Slash once commented that “November Rain” was the sound of the band breaking up. If that’s the case, the rest of Use Your Illusion must be the sound of them being drawn and quartered, as this time, the range and stylistic variety of the music matched the schizophrenia of the lyrics: acoustic songs (“You’re Not The First”) next to overblown covers (“Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door”) next to speed-metal (“Right Next Door To Hell”) next to outrageously mean-spirited anthems (“Get in the Ring”), slices of pop (“Yesterdays”), some charming Stones retreads (“Dust N’ Bones”), even a left-field industrial piece (“My World”), all sandwiched between a handful of stunning piano-driven epics. But by some miracle, their reach seldom exceeded their grasp. The highpoints of Use Your Illusion are many.

Lyrically, Axl’s zigzagging was no less breathtaking than on Appetite, but now with an added degree of intellectual pomp. “Don’t Cry” was undeniably sentimental when paired with the absurdly confrontational “Perfect Crime”. The defiantly aggressive “You Could Be Mine” comes right after the existential vulnerability of the nine-minute tour-de-force “Estranged.” The sheer volume of language in “Garden of Eden” is astounding, its global scope wildly out of step with its punk arrangement.[7] And to say that the attitudes toward women on Use Your Illusion were all over the place would be a gross understatement.

The audacity on display is simply staggering, evidence not only of the force of Axl’s reaction to Appetite, but also of the breakthrough that the debut represented for him, confidence-wise. Whatever remnant of self-acceptance he found in his success appeared to have given him the courage to delve deeper into himself, dredging up some genuinely profound words to accompany the fantastic tunes. Perhaps the “assurance” achieved in that first album gave Axl the internal space to embrace an impressively broad chunk of the human spectrum. Whatever the case, we are all richer for it.

It should come as no surprise that Axl’s life-long boxing match with the Law is not relegated to subtext on Use Your Illusion; it occupies central stage. In fact, one of the record’s overarching themes is his fear of being caged. The titles alone are positively soaked with accusation: “Don’t Damn Me” is a manifesto of defensiveness, “Back Off” responds to perceived romantic demands in a typically threatening manner, “Civil War” makes things political, and “Dead Horse” has self-justifying victimhood written all over it. The giving and receiving of condemnation is pervasive, to say the least.

Yet to continue the metaphor, Axl would win a few rounds before losing the match, chief among them being his magnificently bloated ode to unrequited love, “November Rain”. The single is a crowning moment of 90s music, period. Again, while most of the record may detail the fallout of Law-induced, self-inflicted suffering, “November Rain” points timidly to its answer. The song comes from a man down on his knees, begging for redemption in the form of love and maybe, just maybe, hinting at resurrection in the final verse: “And when your fears subside and shadows still remain / I know that you can love me when there’s no one left to blame.” Perhaps the immortal video for “November Rain” suggests where Axl was going with the lyric. The crucifixes are nearly as ubiquitous in it as they are in the UYI liner notes. Hmmm…

Yet to continue the metaphor, Axl would win a few rounds before losing the match, chief among them being his magnificently bloated ode to unrequited love, “November Rain”. The single is a crowning moment of 90s music, period. Again, while most of the record may detail the fallout of Law-induced, self-inflicted suffering, “November Rain” points timidly to its answer. The song comes from a man down on his knees, begging for redemption in the form of love and maybe, just maybe, hinting at resurrection in the final verse: “And when your fears subside and shadows still remain / I know that you can love me when there’s no one left to blame.” Perhaps the immortal video for “November Rain” suggests where Axl was going with the lyric. The crucifixes are nearly as ubiquitous in it as they are in the UYI liner notes. Hmmm…

Critics did not go easy on the record, deriding the absurdity of its scope and dismissing it as self-indulgent, evidence that the danger of Appetite had been domesticated (it hadn’t). Too many songs, they complained—too much production, too much ambition, too much, period. [8] Some would say their gripes were borne out during the album’s promotion, as the once frightening gang seemed to morph into cartoon characters worthy of their comic-book names (Axl, Slash, Izzy, Duff, and… Matt Sorum). Their personae had somehow come to overshadow their personalities, and the writing was on the wall—“use your illusion”, indeed. The freedom and camaraderie had evaporated, as evidenced in the songwriting credits, which were now ridiculously precise—you could almost see the lawsuits brewing between the letters.[9]

Axl, being no dummy, predicted it all quite adroitly in his underrated masterpiece “Breakdown”, which doubles as a eulogy for the band. “Funny how everything was roses when we held on to the guns / Just because you’re winning don’t mean you’re the lucky ones”.

The commercial response was more enthusiastic than the critical one, though nowhere near the level of Appetite. Perhaps the pre-existing fanbase were put off by Axl’s Freddy Mercury obsession. Or perhaps popular sensibilities were shifting toward outspoken Axl critic Kurt Cobain. Maybe the accompanying videos were simply too pretentious. Who knows. You couldn’t call the project a failure, as it certainly kept the band in the spotlight and cemented their position as global superstars. And yet, UYI seemed to please everyone and no one. You might say that the illusion of living up to Appetite proved to be unusable; 1994 was the last time the world would hear from the original line-up of the band. But the story was far from over. The Law was not done with Axl Rose, nor he with it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dk7aldE3KzE

Left So Far Out From the Shore

“The name [Guns N’ Roses] helped the music [on Chinese Democracy] more than you could ever know, and I’m not talking in regards to studios and budgets. I mean it as in being pushed by something, and having to get the music to a place where I can find my peace regardless of what anyone says.” —Axl Rose, 2009

After the breakup of the original band, a deafening silence descended. There were “wars and rumors of wars” for a while, but after the forgettable The Spaghetti Incident? and a pretty atrocious cover of “Sympathy for the Devil”, the greatest and most globally popular American band of the era faded from view. Completely. The turnaround was dramatic and characteristically extreme—all of a sudden it was the year 2000, and an Axl-sized hole was gaping in the music scene.

Axl has claimed that his prolonged absence was not a matter of perfectionism. He refers instead to an unrelenting barrage of woes, both artistic and litigious in nature, that kept him from putting out new material. The revolving door of personnel and management seemed to tell a different tale: that of an erratic artist getting more erratic.

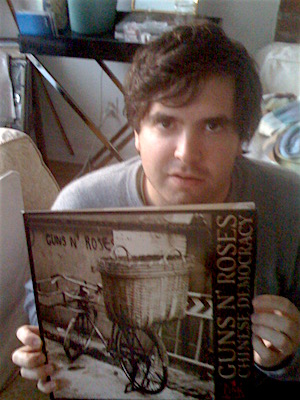

Nov 22, 2008 – the day *before* the official release date!

Regardless of what was actually going on behind closed doors, the fourteen-years-in-the-making Chinese Democracy has come to function as shorthand for creative paralysis. Five years would have been a long time, but this was no ordinary band, nor man. Axl was out to prove himself sans Slash, to demonstrate conclusively that he was the driving force behind Guns N’ Roses all along, that the critics had been wrong about him and, of course, that the music in his head was worth the wait (and personal cost). As the years went by, the standards naturally rose… and rose… and rose, pun intended. Axl rationalized the process this way:

“In regard to so-called perfectionism, I feel that has a lot to do with your goals or requirements with whatever one’s doing or creating. Different levels may be required for different objectives. If you’re making brakes for a vehicle, what’s required? It’s all relative, right? You try to make the best calls you can at any given moment and go from there. Generally, when this term is used by others in regard to me or how I work, it’s said in a negative way or as an excuse for their shortcomings—and again by my detractors.”[10]

That Chinese Democracy ever came out is a miracle. It did so without any promotional help from its author—no videos and only a handful of low-profile interviews. But come out it did, even if the end product ironically felt a little rushed: the lyric booklet contained some typos, Axl alluded in interviews to a “real cover” that would eventually see the light of day, etc. So even in its final release there was something tentative, a hedging of bets, the sense that it had been clutched from hands that had not quite finished with it.

Yet despite a few rough edges production-wise, the songs themselves hold together remarkably well. Interlocking themes of reproach, justification, blame-shifting, accusation, and exhaustion comprise the record. Chinese Democracy is what happens when you marry the extreme end of a Law-based mentality to an ungodly (or godly, depending on your perspective) orchestra of guitars. As such, it is a brilliant and deeply misunderstood piece of work.

Not surprisingly, Chinese Democracy was criticized for being overbaked and overproduced, somehow both expansive and claustrophobic at the same time, and way too insular in its spleen and sheen. Axl was dismissed as “no longer relevant”—as if “relevance” had ever had anything to do with his music. Lord knows restraint had never been his strong suit, either. In the muted and somewhat antagonistic reception, one almost got the feeling that Axl had been right all along about the critics, that he was being judged by people who were at odds with him as a person and therefore couldn’t hear his material for what it was. This was their chance to chide and ‘correct’ his clearly inflated sense of self, rather than bask in its awesome glory.

What about the songs themselves? “Better” is a peerless self-pity anthem (“No one ever told me when I was alone / They just thought I’d know better”). It likely would have been a hit of some kind if the band had done anything to promote it. “Street of Dreams”, which was maligned for sounding like a Broadway tune (it doesn’t), summons as much uplift as Axl can muster for a song about loss. One of several epics, “There Was A Time” surfs a timeless groove to communicate extraordinary regret and self-reproach before ending with roughly four consecutive guitar solos, each better than the one before it. At first blush, “Catcher in the Rye” seems to let the sunshine in briefly—until you realize the lyrics are about resignation and violence. These are all dense statements, a long way from “Used to Love Her”.

But the second half of the record is where things get really interesting. First, “I.R.S.” brings the sparring senses of condemnation and justification to a boil:

Feeling like I’ve done way more than wrong

Feeling like I’m living inside of this song

Feeling like I’m just too tired to care

Feeling like I done more than my share…

There’s not anymore that I can do

The words aren’t arbitrary. Axl is literally appealing to the law—the IRS and the FBI—for exoneration. Yet to live by the sword is to die by it. There is no end, no possible solution to the justification he craves. Not on this earth at least. Instead of peace, he finds exhaustion and resentment.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xzvV4x5nIgE

Next, on the majestic “Madagascar”, arguably both the album’s highpoint and mission statement, Axl’s defiance turns into defeat and outright despondency (“I won’t be told anymore / That I’ve been… left so far out from the shore / That I can’t find my way back, my way anymore”). “Forgive them that tear down my soul”, the weary singer pleads, and for once, his messianic tendencies enhance the music rather than weigh it down. It doesn’t hurt that the final crescendo peaks with Martin Luther King’s “Free At Last” speech, with MLK appealing to “the power that can make a way out of no way”. The song is the closest he comes to a prayer.

“Madagascar” is followed by “This I Love”, which finds Axl at his most brokenhearted and baroque, boasting what may be the best use of strings in their entire catalogue. Finally, the album ends with the masterful “Prostitute”, a conflicted plea for clemency as well as apology for the entire project. It’s not terribly cut and dry—is he singing to himself? A jilted lover? His former band? God? All of the above?—but that’s part of the song’s genius. “Prostitute” captures the sorrow at the heart of the record perfectly. But it adds something else. If you listen closely, amidst all the self-excoriation and spite and sadness, there’s an ever-so-slight whiff of repentance. “What would you say if I told you that I’m to blame?”, Axl asks mid-way through. “Please be kind”, he begs his listener, and only a hardened heart wouldn’t feel compassion for such a tortured soul. Could it be that the final stop on the bus from Lafayette is humility? One can only hope.

Of course, Chinese Democracy cannot really be evaluated as a mere collection of songs. It is so much more: an album-length transmission from the lonely, neurotic, self-absorbed and yet utterly captivating Planet Axl. It sounds like nothing else, not even GNR. That it wouldn’t live up to expectation was a foregone conclusion, not to mention one of the record’s primary themes. To criticize it for not being something else is to misunderstand it.

With Chinese Democracy, Axl delivered an exhaustive musical survey of internal reactions to the Law: self-justification, blame, anger, paranoia, victimization, despair, self-pity, alienation, and, yes, a shred of humility. That its production and promotion would be mired in paralysis, litigation and confusion only completes the picture of a self-defeating record, about self-defeat, that was defeated by itself! Suffice it to say, Chinese Democracy is not much of a party record. Time will only tell if it is Axl’s final testament. I am hopeful but not optimistic.

Don’t You Cry (Tonight)

Speaking of hope, does the secret history of W. Axl Rose contain any? Or is his story the tale of talented but troubled man disappearing into a black hole of recrimination and delusion? Is it ultimately a cautionary tale about the futility of fighting pyrotechnics with pyrotechnics, law with law? Thankfully, no one’s life can be wholly reduced to whatever themes it may illustrate. It is not for us to know what’s in Axl’s mind, heart, or soul. If we did, who knows, it might take some of the luster out of his music.

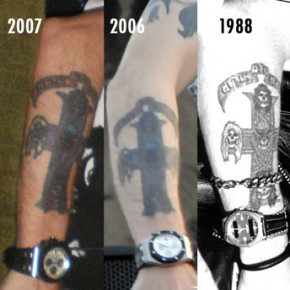

No, the only hope I can see is the one hanging around Axl’s neck and tattooed on his arm. Seriously. Despite his severe misgivings about the faith in which he was raised, crosses dominate not only the UYI-era videos, but his image since then as well. These days he seldom appears on stage without an enormous cross necklace, an accessory which could be dismissed as a fashion statement, were it not accompanied by his outspoken affection for and collection of antique crucifixes.

The interior of Axl’s house – from the Estranged video.

One can only presume that something about the central symbol of Christianity must have stuck with him. It surely isn’t just that he fancies himself a bit of rock messiah, though clearly he does. Having traveled from the Nazareth of Lafayette to the Jerusalem of the Hollywood Hills only to be met with resistance and suffering, you can understand how he might identify with our Lord.

I suspect it goes deeper. Fortune and shame may have eaten Axl alive, judgment and criticism may have dogged him inside and out, but apparently Calvary never lost its attraction. Not even the most toxic of religious upbringings, decadent of worldly indulgences, or protracted of psychological quagmires could strip it of its power. Perhaps this is because the cross of Christ addresses none more directly than those who have been ravaged by the law (and ravaged in return). It summarizes judgment at its most visceral and inescapable—indeed, the cycle of recrimination kills God himself. Yet in speaking of death and ‘destruction’ and the worst of human nature, it also points beyond those things, to the One who came not to condemn the world but to save it, to bring an “end of the law” (Romans 10:4) and justify those who cannot justify themselves, no matter how many songs they write or rants they go on. In other words, that glittery crucifix of Axl’s symbolizes the hope that, like November rain, the fearful cycle of condemnation and reactivity will not last forever, the hope that, yes, there’s a heaven above you, baby.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CWUX4GoYiMg

[1] Among Axl’s many achievements, but a relatively unsung one, is the fact that he taught an entire generation of boys how to curse.

[2] What is usually meant by that label is that they are the last truly great rock n’ roll band to emerge (and be accepted as such) before irony, via grunge, made the whole notion untenable.

[3] William Axl Rose, interview by Del James, RIP Magazine, November, 1992.

[4] “Pelagianism” is another word for this strand of Christianity, referring to a fourth century British monk named Pelagius, who implicitly denied the doctrine of original sin, affirming instead the ability of humans to be righteous by the exercise of their free will. He essentially believed that we do our share of the legwork in the Christian life. His views were condemned as heresy by the Church in 418 AD. It did not stop them from spreading.

[5] In an infamous episode during the tour for UYI, Axl allegedly presented Izzy Stradlin, his childhood friend, with a contract to reduce his royalties, refusing to go on stage until it had been signed. Izzy quit the band soon thereafter.

[6] Considering the legendary wait between UYI and the album that followed it, Chinese Democracy, it’s easy to forget that Use Your Illusion was delayed for over a year.

[7] The moral vision in “Garden of Eden” and “Civil War” is hard to ignore, even for a purportedly ‘amoral’ band like GNR. Both songs also attest to another relatively unsung aspect of their musicality: the Gunners’ unparalleled mastery of the song intro.

[8] The perennial criticism of UYI is that if they’d reined it in, they could have made a stunning single album instead of two uneven, overlong CDs. I have tried every which way to figure out a tracklisting that would fit on one disc and maintain the essence of the record. It cannot be done. What can be done, however, would be to make UYI a double LP (as opposed to the six sides of vinyl it would take to put it out in its released form). An ideal, one-volume Use Your Illusion would look like this:

Side 1: You Could Be Mine / Garden of Eden / Bad Obsession / Don’t Cry / Pretty Tied Up

Side 2: Breakdown / Perfect Crime / Double Talkin’ Jive / November Rain

Side 3: Back Off / 14 Years / Civil War / Bad Apples

Side 4: Yesterdays / Locomotive / Dead Horse / Estranged

[9] This is also likely why Use Your Illusion has never been re-released and probably never will be. Same with Appetite. Sigh.

[10] Larry Fitzmaurice, “Axl Rose Talks ‘Democracy,’ New Songs, Slash”, Spin, February 27, 2009.

COMMENTS

16 responses to “The Secret History of William Axl Rose [Super Deluxe Edition]”

Leave a Reply

Thank you for share this! I think is amazing how an artist”s heart can be shown with every single thing he does even most of listeners can be perceived it if only one soul can’t be feeling raise from ourself darkness with the sound of a friendly voice that say I know what you are feeling and don’t let you down. That is friendship. That is love

This is great. Absolutely nails it. Fantastic stuff thank you for a great read and making my lunchbreak

His name isn’t William anymore, legally it’s W.

Amazing article. I grew up listening to GNR and “November Rain” is one of my favorite songs EVER. They will forever stand as one of my top bands. Loved how you explained everything through Law/Gospel lenses. What a lovely read.Thanks, David.

This is so good! !

Where can we buy the book!?

Brilliant article.