Click here for this week’s episode of The Mockingcast.

Thank You For Playing (2016) – Official Teaser from Thank You For Playing on Vimeo.

1. I’m a little embarrassed we haven’t given this initial story its due yet. Given the nature of the content and my own stage in life, I suppose I’ve been putting it off. But it’s simply too powerful and beautiful to ignore any longer, a testament to the very best that Christianity has to offer the world, and in a highly unexpected form. I’m referring to the creation and release of what is being called “the most profound video game ever made,” That Dragon, Cancer. Doesn’t matter if you’re a non-gamer, or even an anti-gamer, you’ll need a box of tissues to absorb what married couple Ryan and Amy Green have done in turning their son Joel’s tragic case of terminal cancer into an immersive experience for others to “play”. Ryan and Amy developed the game together, incorporating their Christian faith into its mechanics in ways that are equal parts courageous and creative (and not the least bit contrived). It’s difficult to describe. The place to start, especially if you’re snowed in, is to listen to the brilliant episode of the Reply All podcast in which Ryan and Amy speak for themselves:

If you’d rather read about it, Wired’s lengthy profile is the best thing out there. Again, you really have to take in the whole thing to get a sense of the depth of what they’ve done, but a couple of choice excerpts would be:

[Ryan’s co-programmer on the game, Josh] Larson says his interest in not-games was purely intellectual, not spiritual, but the effort to move beyond performance-based reward systems seems to track with some of his deeply held philosophical beliefs. “The idea of grace is that you don’t have to do something good to earn your salvation,” he says. “People are always so concerned about what you do in a game, and they can be that way about life too. Whereas some people, depending on what kind of faith they have or what kind of person they are, that’s not necessarily what defines them.”…

Finally arrives in April!

According to Green’s original design, the game would end with you, the player, facing an array of dozens of levers. For a while you would yank and tug at them, trying to discern the pattern that would unlock the game’s conclusion. After a few minutes, the camera would pan up to reveal the back of the console, its wires frayed and disconnected. The levers were false, the game’s designer was in charge, and you were forced to acknowledge that you were powerless to control the outcome.

That conclusion arose directly from the Greens’ religion, their belief that God’s will was beyond human comprehension, that we are operating within a divine plan that we may or may not have the power to influence. Even as they pursued every medical option, their agony was somewhat relieved by the conviction that Joel’s fate was ultimately in God’s hands. “With God we don’t have to do the right things or say the right things to somehow ‘earn’ his healing,” Amy wrote in an online diary soon after Joel’s first biopsy…

Toward the end of the run-through, I enter a giant cathedral. This is the scene that Green has worked on most diligently since Joel’s death. It replaces the lever-pulling scene, his initial idea to urge the player toward accepting his own powerlessness. This is the scene, Green says, that embodies all the wrestling with God he has endured since his son’s death, the scene that once provided answers but now leaves only questions. I brace myself.

2. Before we move on from the heavy stuff, over at The Atlantic, Megan Garber muses on the social media phenomenon of “Grief Policing”, AKA the enforcing, however unconscious, of “the notion that there is but one way to grieve, and that deviation from that way is wrong”. We see this particularly in the, er, wake of a celebrity’s death like David Bowie’s. Mixed in with the various (counterproductive) “Should’s” and little-l laws we can’t seem to help heaping upon something as subjective as grief is a well-founded critique–not so much of public grief but of exhibitionism, where we somehow turn grief into a competitive (and therefore self-justifying) exercise. Oy vey:

The tendency [of “grief policing” is] to tell mourners that, essentially, they’re mourning too much, or not enough… The Internet is, in some sense, returning us to the days before war transformed grief into a largely solitary affair. Public mourning—via Twitter, via Facebook, via Tumblr—has become its own kind of ritual.

Grief policing is a corollary to all that: It is people recognizing that human impulses are hardening into social rituals, and then disliking what those rituals represent… Grief policing may be a fitting thing for a culture that has elevated “you’re doing it wrong” to a kind of Hegelian taunt, that treats every social-media-ed expression as a basis for an argument, and that is on top of it all generally extremely confused about how to mourn “properly.”

3. Okay, you can put the Kleenex away. Social Study of the Week is a tie between “Heavier Waiters Make for Heavier Eating” (“What accounts for this finding? The scientists can only speculate, but Mr. Döring sums up his explanation in a word: “liberation.” In his view, diners with a heavier server felt freer to order more fattening items.”) and “Christians Are Bad at Science When You Remind Them a Lot of People Think Christians Are Bad at Science” which explores the phenomenon of “stereotype threat”, i.e., that people tend to reinforce stereotypes about themselves the more often they are reminded of them. Sort of a negative form of imputation. Fortunately ‘when reminders of the “religion and science don’t mix’ stereotype were removed, ‘performance differences between Christians and non-Christians disappear,’ the study authors write.”

4. In The Wall Street Journal, Lee Siegel explores “How Groucho Marx Invented Modern Comedy”, the gist of which has to do with Groucho’s willingness to break down the public-private barrier on screen. In other words, he would expose and transgress little-l laws about propriety for the sake of ridicule, shock, and entertainment, but also, perhaps, a little freedom. Not sure I completely buy it, but Marx has always struck me as a fascinating character, ht MM:

The Marx Brothers excelled at destroying their integrity as people, and from that point on, comedy began to race past the simple act of making people laugh. Once supposedly funny movies depicted a bunch of actors burning books, as the Marxes do in “Horse Feathers,” humiliating and finally cuckolding a harmless lemonade vendor, as they do in “Duck Soup,” or impersonating a doctor and treating a kind, elderly and trusting dowager with a horse-pill, as Groucho does in “A Day at the Races,” a Pandora’s box of human darkness sprang open. Comedy got set on a path toward the destination it has reached today, where the simple act of saying the publicly unsayable has become more important than the well-constructed joke or the elaborate comic routine.

Perhaps this dizzying, unobstructed freedom is why so many comedians now strive harder and harder for outlaw status, as if defiantly insisting that they will never belong to any club that would have them as a member. Having shamed and defeated all the prohibitions that used to justify comedy’s existence, comedians now seem to be yearning for good old-fashioned censure and repression, simply to feel alive as comedians.

5. In humor, The Onion’s “NCAA Investigating God For Giving Gifts To Athletes” is clever, and McSweeney’s scored a near-masterpiece with “Jamie and Jeff’s Note to the Babysitter“. But nothing made me laugh out loud this week harder than the NPR interview with Jon Benjamin (Bob’s Burgers, Archer, Home Movies) about his new jazz record:

6. This is exciting: Whit Stillman’s Jane Austen adaptation Love and Friendship debuts at Sundance this weekend. Whit did a short interview with Vanity Fair in conjunction with the premiere, one of the exchanges of which is worth reprinting:

Is [Lady Susan, the unfinished manuscript on which Love and Friendship is based] a more “modern” Austen?

Well, I’m sort of anti-modern. So I think it’s what it is. People were very funny in the past, too. And it is a lot funnier than almost anything else written in the 18th century. There’s great comedy written in the 18th century. But this—this is particularly good comedy.

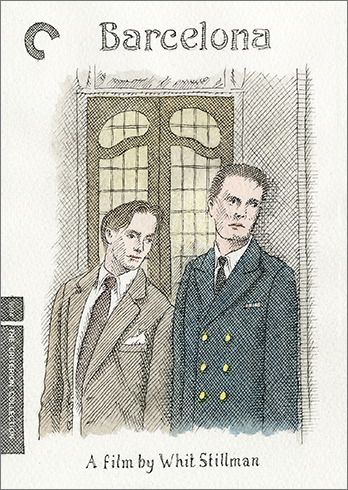

I’m counting the seconds until a wider release–or at least a trailer. Fortunately, this week also brought the announcement that we’ll have the long-awaited Criterion edition of his Barcelona to keep us company while we wait! American films don’t get any better than that one. I mean, no matter how many times I watch the following scene, it never fails to crack me up:

7. In music, any day that brings new music from Paul Westerberg is a very good day indeed. Welcome to the world, Wild Stab. Also, last week saw the release of God Only Knows: Faith, Hope, Love, and The Beach Boys! The back blurb for the book, to which yours truly was honored to contribute an essay, reads as follows:

The Beach Boys are one of rock’s most enduring and enigmatic groups, and while the band has been the subject of numerous biographies and other in-depth studies, there has been no focused evaluation of the religious and spiritual themes in their work.

Spiritual and theological themes are present in much of their work, and when this realization is coupled with Brian Wilson’s mission “to spread the gospel of love through records,” and his sense of music as spiritual–of thinking “pop music is going to be spiritual . . . that’s the direction I want to go”–this is a striking way to explore the band’s music. In God Only Knows, the contributors attempt to come to grips with just a small amount of this band’s massive output–by circling around its theological virtues. Each section of the book is a loose investigation of the guiding topics of faith, hope, and love. Each essay is a free exploration of theological and spiritual themes from the contributor’s own perspectives.

Bowie’s cover of the titular song, embedded above, is known among his fans as his single worst recording. I kind of like it though. This too:

Strays

- Pew reported yesterday that “Americans may be getting less religious, but feelings of spirituality are on the rise”, which dovetails with Rodney Stark’s recent findings.

- Pretty interesting riff on our complicated relationship with the t0-do list via “Why [Adam Grant] Taught Himself to Procrastinate”. Once again, one person’s law is another’s gospel.

- Great reflection on Jim Carrey’s wonderful Golden Globe speech over at Christ Hold Fast, courtesy of Paul Dunk.

- NYC Conference theme and speaker line-up coming next week. Since we’re late on the details, we’ve decided to extend earlybird pre-registration until the end of the month.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply