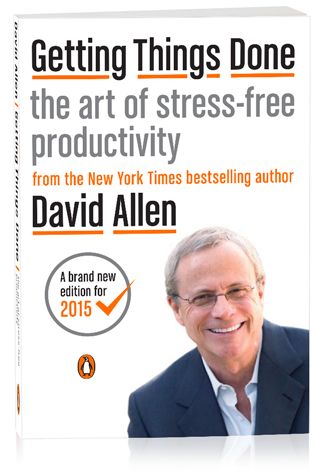

I’ve started reading the second edition of David Allen’s Getting Things Done, mostly because I’m due for a productivity update. If you haven’t heard of Allen’s system (abbreviated and trademarked as GTD)—well, then, you’re clearly not as efficient as you could be. I’ll pray for you.

I’ve started reading the second edition of David Allen’s Getting Things Done, mostly because I’m due for a productivity update. If you haven’t heard of Allen’s system (abbreviated and trademarked as GTD)—well, then, you’re clearly not as efficient as you could be. I’ll pray for you.

I won’t bore you with how, specifically, GTD has allowed me to triage emails and projects and documents and presentations and travel and (shiver) networking and (throw up a little in my mouth) PowerPoint slide decks. I will say this, though: I have never successfully used my precious system outside of work. Never. I installed the (dearly departed) GTD Outlook App on my home computer. I tried The Secret Weapon, a GTD hack of Evernote. I tried using Word documents and a cloud drive. I reorganized my paper files, and now they’re a mess again. I started to clean the garage, and the piles eventually grew and lost any clear demarcations between “storage,” “donate,” and “keep.” I rock productivity at work, but not so much at home.

Part of the reason I have such a difficult time handling things, of course, is that I am pulled in so many directions by my work, family, and community commitments. I cannot focus for very long without interruption, and the lack of focus affects all aspects of my life. Allen eloquently summarizes my current state of affairs as part of a broader cultural trend:

Executives at the top are looking to instill a standard of ruthless execution in themselves, their staffs, and their cultures, as well as how to keep their personal lives appropriately in balance and in play. [. . .]

And, more critically for many, people are not paying appropriate attention to their kids’ school plays, sports games, or going-to-bed questions about life, or they’re simply not able to “be here now,” anywhere, anytime. An ambient angst pervades our society—there’s a sense that somehow there’s probably something we should be doing that we’re not, which creates a tension for which there is no resolution and from which there is no rest.

In the new Getting Things Done tome, as in the original edition, Allen touts his system as solving this precise problem. It is meant to be an all-encompassing system to capture not only every project, commitment, and event in our work or personal lives—he wants us to record every idea we have in lists that are regularly consulted. The reason we would subject ourselves to such a regimen is to completely focus on the present (i.e., single-tasking rather than multitasking):

It’s possible for a person to have an overwhelming number of things to do and still function productively with a clear head and a positive sense of relaxed control. That’s a great way to live and work, at elevated levels of effectiveness and efficiency. It’s also the best way to be fully present with whatever you’re doing, appropriately engaged in the moment. It’s when time disappears, and your attention is completely at your command. What you’re doing is exactly what you ought to be doing, given the whole spectrum of your commitments and interests. You’re fully available. You’re “on.”

https://youtube.com/watch?v=watch%3Fv%3DKf34-wXdl3k

While Allen’s diagnosis of modern work life carries weight, I’m skeptical about the promise emboldened in the prior passage. He may not mean to be be intentionally disingenuous or manipulative, but his assertion dovetails with disturbing trends in the broader self-help literature.

If you are well-versed in self-help, you will recognize, in the passage just quoted, two features that are common to just about every program: personal testimony and the promise of relief. The personal testimony here is that Allen speaks from his experience using and teaching GTD for over a decade, and the promise is that you’ll be “on” nearly all the time, a state that he calls “mind like water.” The effect is to give the reader/user a positive, real-life example and lasting relief from whatever concern brought them to the book/seminar/retreat/YouTube clip in the first place.

The promised relief provides a tangible goal for the user that addresses a persistent need, e.g., debt elimination (Dave Ramsey), lifetime membership (WeightWatchers), or a weekly inbox of zero items (GTD). In a deeper sense, though, there is an intangible benefit that one aspires to achieve in just about every successful self-help construct, e.g., financial peace, lifelong good health, or mind like water.

In each of these three programs, at least in my own experience, there’s an accompanying anxiety over not achieving the end goal, the sense that the intangible benefit—what I’m really after—is unattainable. I’ll never achieve financial peace so long as I am in debt, I’ll never feel truly healthy until I can maintain a BMI of 20, and I’ll never feel settled about my life until I can fully and faithfully apply GTD.

The anxiety shows a flaw both in the systems and my expectations of them. The systems derive much of their membership base by convincing people that the encouraged practices and attitudes are a way of life. This is why you never mention “whole life insurance” to a Financial Peace devotee (I dare you). My experience tells me, however, that few people have the commitment to stick to even one system for very long. The disappointment at failing is thus increased, because the system was sold as a solution for better living, period. The point here is not that self-help is demonic or inherently exploitative; rather, they are simply systems which were crafted with original sin in the background. No self-help system can perfectly meet everyone’s needs—or even the needs of everyone in a target audience—because all participants are subject to original sin.

Which brings me to the final piece: how we react when our repeated self-help campaigns go south. Personally, I’ve tended to regard them as failures, partly because I get briefly fanatical about them before sliding into a steep decline in interest and commitment. And so my mind has cataloged all of the failed attempts to improve my life. Yet I still dream of the moment, three or five or 10 years from now, when my long-term dedication pays off. Then I sit down on the sofa, sigh out of exhaustion, and watch the next episode of Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., and the one after that.

The fallacy I’ve been operating under was well-described a few years ago in an article by Alina Tugend that was blogged by DZ:

[W]e can’t go around with the idea that “one day I’ll arrive; one day I’ll be whole,” [Hollee Schwartz Temple] said. “It’s an illusion that one day I’ll be fixed.”

Such constant searching, she said, leads to a sense that you’re waiting to live your life rather than living it. Or you’ll feel that you’re always falling short, because rarely is the road to self-improvement easy or straightforward, and it’s certainly not the same for everyone.

Tugend expresses a point that I’ve noticed in self-help but rarely see expressed: people succeed/fail at programs for many reasons other than the presence or absence of hard work. Level of energy, wealth, health, genetic factors, family peace/chaos—all of these factors and more play a part. So it is is fruitless to be anxious about whether I will ever achieve mind like water. I’m not going to quit GTD, as it is truly helpful in my work; I might, however, cool down the anxiety about implementing it at home. That is, the next time my mind goes on a “when I complete all my goals through hard work” bender, rather than applying an unrealistically high anthropology to myself, I might remember who I really am, that these steps will not really change me.

But there I go again down resolution road – or river, as the case may be.

Self-help is an inescapable part of modern life, and objections to it usually end in a diluted form of whatever is being criticized. One can only hope, therefore, that we all might continue to find rest in the redemptive water, not of mind, but of baptism.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply