This is the second installment of author Ted Scofield’s series on “everybody else’s biggest problem.” If you missed his introduction to the series, you can read it here. New installments will be posted every two weeks, on Tuesdays.

“The United States has become a greedier, meaner, colder, more selfish, and more uncaring place. This is no wild inferential speculation but, rather, the informed consensus of the American people.” – James Patterson & Peter Kim, The Day America Told the Truth

“James Patterson is an American author with a net worth of $350 million … Patterson earned $90 million in the last 12 months, bringing his total career earnings to $700 million

over the last decade.” – Celebrity Net Worth & Forbes

Greed is an important underlying theme of my novel, Eat What You Kill, and while researching it I stumbled upon two fascinating data sets which launched me on this quest to define greed.

Before we get to the data, let’s start with what I hope is not only obvious but pivotally important to this entire series: Collectively the vast majority of people believe greed (that is, the pursuit of money and the stuff it buys) is a problem, for families, communities, America, our Earth and, yes, even the whole of human civilization. We’ll look at the numbers in a moment; first, here’s a sample of opinions from our popular culture:

- “Greed undoes family and community ties and undermines the very values on which society and civilization are founded,” a physician counseled in Psychology Today.

- “Greed is more than simple avarice; greed robs and hurts and even kills people,” Pastor Dwayne Westerman argues.

- “Your greed has got to end! Your greed is destroying America, and we are going to end your greed!” Bernie Sanders exclaimed on July 19, 2015, addressing unidentified “billionaires” who were not present at the time.

- “Unconstrained greed is the heresy of our times … if it is not restrained, then the consequence could well be the total collapse of the society in which we live,” says British intellectual Stewart Sutherland in his 2014 book Greed.

- “Human civilization will collapse unless the greed culture is stopped,” The Telegraph proclaimed.

- “Greed, in particular the greed of corporations and billionaire oligarchs, is driving human civilization and the biosphere towards disaster,” we read recently.

Okay, so the politicians, pundits and preachers tell us that greed is B-A-D. Do we commoners agree? A legion of polls suggests we do.

Zogby recently conducted a large benchmark poll in which respondents identified “greed/materialism” as the number one “most urgent problem in American culture.” Number one! Most urgent! “Poverty/economic justice” finished in second place.

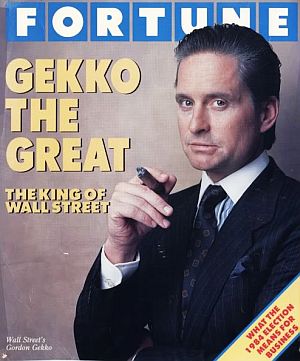

In a 2014 Vanity Fair poll, 78% of Americans disagreed with the famous Gordon Gekko quote “Greed is good.” Only 19% agreed. Salon.com recently warned “Wall Street greed refuses to die: How lobbyists & dark-money groups are exposing us to another disaster” and we reject greed as an appropriate motivator: A recent Marist poll revealed that 74% of Americans see business decisions based on greed as morally wrong.

In a 2014 Vanity Fair poll, 78% of Americans disagreed with the famous Gordon Gekko quote “Greed is good.” Only 19% agreed. Salon.com recently warned “Wall Street greed refuses to die: How lobbyists & dark-money groups are exposing us to another disaster” and we reject greed as an appropriate motivator: A recent Marist poll revealed that 74% of Americans see business decisions based on greed as morally wrong.

Back in 1992, a national Gallup survey revealed that 75% of Americans believe there is “too much emphasis on money” in our nation. A more recent poll of Economist readers asked “What is the deadliest sin?” and, yes, greed ranked number one.

Pollster Richard Harwood sums it up in the book Affluenza: “There is a universal feeling in this nation that we’ve become too materialistic, too greedy, too self-absorbed, too selfish….”

Finally, we seem to have grown weary and dubious of incessant technology “improvements.” Although Bill Gates once said “Microsoft is not about greed; it’s about innovation and fairness,” for the first time in fifteen years, a 2015 poll recorded a decline in our faith in the motivation for innovation: 30% said it’s intended to improve people’s lives. Fifty-four percent answered “greed.” Did you hear that, Apple? I just bought my iPhone 6S; I don’t need an upgrade just yet.

Anecdotally, my research mirrors both pop culture and polls, and it doesn’t matter if the group is a room full of ramen-dependent students at a Christian university or wealthy Wall Street friends from my b-school and law school days. When asked if greed is a problem in our society, at least 75% of the queried say “Yes.”

Who, me?

So, we agree, greed is a problem in our culture, but it is your problem? Are you greedy?

My guess is you’re thinking right now, No, it is not my problem, I am not greedy. Please don’t feel guilty or ashamed if that is your reaction. As Mark Putnam, the President of the Global Ethics University (GEC), says, “Ask anyone the question ‘Are you greedy?’ and most will deny it.” So, if denial is your first reaction, and it’s definitely mine, don’t worry, you’re in good company.

My guess is you’re thinking right now, No, it is not my problem, I am not greedy. Please don’t feel guilty or ashamed if that is your reaction. As Mark Putnam, the President of the Global Ethics University (GEC), says, “Ask anyone the question ‘Are you greedy?’ and most will deny it.” So, if denial is your first reaction, and it’s definitely mine, don’t worry, you’re in good company.

When the BBC conducted a poll on the seven deadly sins (anger, envy, gluttony, greed, lust, pride and sloth), greed was last on the list in answer to two questions: Which sin have you ever committed? and Which sin have you committed in the past month? Plenty of Brits copped to being lazy, proud, envious and angry. But greedy? Seventh out of seven, last on the list.

The Catholic faith gives us two relevant data points. In a Vatican study of confessions, greed was the least common deadly sin reported by men and the second least reported by women. (Catholic moms are far too busy for sloth, apparently.) A poll on a Catholic dating site asked “Of the seven deadly sins, which do you struggle with the most?” Greed was once again last on the list, with only 2.7% admitting to it. (No surprise, I guess, 47% of Catholic singles admitted to struggling with lust, the number one ranked sin.)

I posted my own poll on Survey Monkey and various social media platforms. Five hundred of my contacts responded:

I believe I have a problem with:

- Anger – 30%

- Envy – 30%

- Gluttony – 28%

- Pride – 24%

- Lust – 22%

- Sloth – 18%

- Greed – 8%

Polls on societal or collective greed also flip when made personal. For example, in that national Gallup survey where 75% lamented the emphasis on money, a full 80% said owning a beautiful home, a new car and other nice stuff was absolutely essential or important. When asked why they chose their present vocation, the number one answer was … MONEY.

Plenty of commentators lament our individual unwillingness to admit to greed. My pastor, Tim Keller, argues “even though it is clear that the world is filled with greed and materialism, almost no one thinks it is true of them … Greed hides itself from the victim.” Pastor Dwayne Westerman adds an apt metaphor: “It is also insidious, burrowing its way into the lives of people like a worm into an apple, unnoticed until the rot begins from the inside out.” The GEC’s Mark Putnam summarizes the reality succinctly: “Few people identify themselves as greedy.”

Bernice Johnson Reagon and her musical group Sweet Honey in the Rock sing:

Maybe you don’t really know exactly what I mean

You don’t really want to know about your and my greed.You may wonder whether you are infected by greed

If you have to ask, then this song you really need.Greed is sneaky and hard to detect in myself

It shows up clearly in everybody else.

You don’t really want to know about your and my greed. Reagon is, of course, referencing denial. Tim Keller also concludes that when it comes to our own greed, “we are in denial.”

David P. Levine is a professor of economics at the University of Denver. In truly academic fashion, he says: “Though prominent in shaping our thinking about self-interest, the part played by greed is as often denied as acknowledged. The denial of greed expresses the ambivalence it provokes, which stems from the danger it poses or seems to pose.”

Levine argues that greed is dangerous because of “the link between greed and destructiveness.” Because greed is indeed destructive, our culture must repress it, must change it into an acceptable form. Greed must become something it is not. Greed must be someone else’s problem. Greed must be denied.

But could it really be that simple? Are we greedy humans in denial of our own avarice? Is James Patterson, the author who has amassed a net worth of $350 million yet rails against greed, in denial? Is denial why we see it in everyone but ourselves?

I don’t think so. How can we deny what we cannot define, what we do not, or will not, understand? I have yet to find half a dozen people who can agree on a generally applicable definition of greed. Unlike anger or lust or sloth or envy, greed defies explanation, hence my current quest.

So where do we go from here?

When analyzing this surprisingly mysterious concept, greed, when attempting to reach a standard definition, eight factors emerge, each more enigmatic than the last, and in the next installment we’ll examine the most obvious of the eight.

Until then, I’ll give you something to ponder.

In Luke 12, Jesus says “Watch out! Be on your guard against all kinds of greed; life does not consist in an abundance of possessions.”

What is “abundance”? How much is too much?

COMMENTS

5 responses to “Everybody Else’s Biggest Problem, Pt. 2: The Collapse of Human Civilization”

Leave a Reply

Guilty as charged. I have never thought of myself as greedy but think many other people are, especially in New York. I think (or thought) greed is a massive problem in our culture but not my own. Time to reevaluate. Great piece!

I hope you will address greed outside of the context of money and material possessions. Can we be greedy in our faith? Can our greed for acknowledgement and attention lead us away from God. Is it greed that possesses us when our time is consumed with a singular motivation? Can greed be good if in fact the entity that is deemed greedy doesn’t hoard but redirects resources it acquires to what it considers its own worthwhile causes, which simply may not be another’s cause but worthwhile nonetheless? Are we greedy if we store grain in anticipation and fear of drought, or greedy if in fact we keep that grain for our progeny because our instincts to protect and provide for our family move within us?

Are greed and ambition the opposite sides of the same coin ? Or, are they in different domains completely? The human capacity for attribution bias seems to fit this context.