“What is greed?” It’s a good question, and it is one which was posed to me by Ted Scofield during his breakout at the Mockingbird Conference a month ago. (You can hear the audio recording here.) According to Ted, several statistics and polls reveal that we Americans collectively see greed as a societal problem yet deny it as an issue in our individual lives. Merely citing the addictive behavior around smartphone upgrades revealed to me, a self-professed wannabe techie, that there is a problem: “We have grown weary and dubious of all the technology upgrades. For the first time in a 15 year history of this poll, now more than half of us believe that the reason for Apple updating iPhones and for Microsoft putting out a new Windows version—it’s no longer to make our lives better—the poll now shows that we answered it’s for greed.”

As he said it, there I was feeling guilty as ever: not a new smartphone this time, just a pre-order of the Apple Watch I had made two days beforehand.

But back to the question: What is greed? We all, of course, know that it has something to do with stuff, money, possessions. If you wanted to express it in emoji terms, you might choose the moneybag, jet, boat, and diamond ring (and don’t forget the appropriate hashtag). So is greed the possession of a certain amount of money? Would, say, making $150,000 a year be the point at which one becomes greedy? Is the owner of a four bedroom house guiltier than the owner of a three bedroom house? Is the person who drives a Mercedes greedier than the one who drives a Toyota? Where exactly is that threshold for greediness?

But back to the question: What is greed? We all, of course, know that it has something to do with stuff, money, possessions. If you wanted to express it in emoji terms, you might choose the moneybag, jet, boat, and diamond ring (and don’t forget the appropriate hashtag). So is greed the possession of a certain amount of money? Would, say, making $150,000 a year be the point at which one becomes greedy? Is the owner of a four bedroom house guiltier than the owner of a three bedroom house? Is the person who drives a Mercedes greedier than the one who drives a Toyota? Where exactly is that threshold for greediness?

The easy and immediate attempt to quantify greed does not appear to mesh with everyday experience, and any hard and fast rule surely has to be arbitrary. So might one be able to move the issue internally, rendering it a qualitative problem? In other words, it seems a safer bet that greed has more to do with wanting things rather than merely possessing them. But continuing down this path leads to a similar dead-end: at what point does desire become excessive and thus greed?

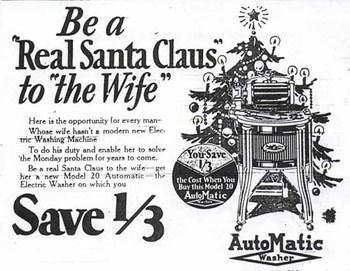

The sense of greed we all have on a national scale is likely due to the fact that we live in a consumerist society. (Remember that unnecessary smartphone upgrade?) Consumerism bears striking similarities to greed and is usually defined by the possession of things. But a consumer does not act to possess things; no, he or she lives merely for the pursuit of things.

As William Cavanaugh writes in Being Consumed:

In consumer culture, dissatisfaction and satisfaction cease to be opposites, for pleasure is not so much in the possession of things as in their pursuit. There is pleasure in the pursuit of novelty, and the pleasure resides not so much in having as in wanting. Once we have obtained an item, it brings desire to a temporary halt, and the item loses some of its appeal. Possession kills desire; familiarity breeds contempt. That is why shopping, not buying itself, is the heart of consumerism. The consumerist spirit is a restless spirit, typified by detachment, because desire must be constantly kept on the move.

If Cavanaugh is right, that would explain why as soon as the iPhone 6 was released, there was already talk of what the next iteration might look like. In a consumerist society, an individual’s desire is unlimited, and because desire is unlimited, goods are scarce. It is not that we want to own more things; it is that we pursue them endlessly, discarding them nearly as soon as we pick them up.

Such desire is fueled in a world that no longer has an overarching story, quite characteristic of our postmodern, secular society. When the narrative that shapes a culture’s identity has collapsed, there is no longer a shared past or future, and the individual self must retreat to itself to shape its own identity; when human society no longer has a chief end (a telos), when it no longer has a future, when all we are is a group of autonomous individuals, the self reigns and desire runs rampant. The postmodern self, in other words, is a storyless self, one who is bound to the present because there exists no narrative identity. The best marketing companies know this, which is why their ad campaigns will tell consumers less about a product and more about an experience. Or more precisely, they create a larger mythological narrative to fill the void that remains in a storyless society. In Cavanaugh’s words,

Associating in one’s mind with certain brands gives a sense of identity: one identifies one’s self with certain images and values that are associated with the brand. Branding offers opportunities to take on a new self, to perform an ‘extreme makeover’ and become a new person.

Thus, consumerism, it would seem, goes hand-in-hand with a secular society (if we grant the religious-secular bifurcation), yet it ironically reveals the religious undertone of secularism on the ground. The secular sphere is often seen as the space that remains when all appeals to religion have been removed, yet the human impulse to create a larger narrative remains. In our postmodern, secular society where we no longer have a larger story to make sense of ourselves, the self can never rest, revealing consumerism and greed’s law-centeredness.

So in a culture that can never see past the present, could it be that the Triune God’s story of incarnate presence remains truly countercultural? One wonders if this story—the narrative of God’s one-way love revealed in Israel and culminating in Jesus Christ—is the story that opens to a future that sets the impatient consumerist self to rest. And this is precisely the story the Church rehearses again and again each week as the Spirit gathers her together to be addressed by the Word, washed in baptism, and fed in the Eucharist “until he comes” (1 Cor 11:26): no longer consuming, but consumed into a larger body (as Cavanaugh puts it).

The announcement of grace from the God who speaks effects a radical decentering of the self. It calls one outside him- or herself to participate in God’s own continual self-giving. In the Gospel, even we storyless selves receive an assured future, an end, a telos that is firmly rooted in Another’s abounding goodness and love.

COMMENTS

12 responses to “The Storyless Self: Thoughts on Greed, Consumerism, and Desire”

Leave a Reply

Stellar!

What the heart desires, the will chooses, and the mind justifies..Cranmer.Its a heart issue primarily a quantity issue secondarily.We hate the other because they have been blessed by God More than us therefore we hate God because he has given us less.If we loved God with our whole being then we could ..would love our neighbor.The enemy prowls whispering lies seeking to devour us.The language of judgement and condemnation toward the other is our desire to be god.Only one has been able to withstand the tempter, Jesus Christ.”Lord,save me!”

This made me think of Aziz Ansari’s bit on making plans with flaky people… consumerism has even infiltrated our relationships.

Great post.

Phil, thanks! And great point on the relationships comment. I would bet that we are consumerists in all sorts of ways, from relationships to the way we treat church: we always keep our options open and are ready to discard them at a moment’s notice. If you have a YouTube link to the Aziz Ansari piece, I’d love to see it!

Great point about how we treat church. I recently had a conversation with a friend about this. We both attend the same gathering and yet we have extremely different views from one another on the expression/experience of the church (low to high). Both views should have neither of us as committed members to the community we are a part of (and the topic of our own “church shopping” experiences came up). Still, there we were, committed as brothers to one another, committed to the community… walking together to allow the whole to be greater than the sum of its parts. The tendency towards the “I follow Paul” – “I follow Apollos” seems to continue to find its way – or maybe that’s not sad; I’m not sure – either way, for that there is grace.

If you search youtube for “Aziz Ansari – Making Plans with Flaky People” you will find a clip. I would post it here, but it has some “language” – and while that doesn’t bother me, I want to be respectful to others – so, it is your choice if you want to view =)

All right, friends. I had a comment posted here. What happened to it?

Mike-

If you want to rephrase your comment in a way that doesn’t disparage Brandon (or his education) personally, I’m happy to have it up. Otherwise, I’m afraid it’s a no-go.

DZ

All right, Mr. Zahl, I’ll go about it this way.

In response to Mr. Bennett, I would love to believe as much as any of you that culture is solely responsible for inducing people to cast off traditional restraints, but I do not think that explanation holds up under historical scrutiny. If you say you believe in original sin (as I do), then you cannot let individuals off the hook. Changing the stories people tell themselves does not, pace current opinion, necessary change the people themselves. Only the Gospel of Jesus and Him crucified does that. It not only crucifies (slowly at times, admittedly) the desires that give root to the consumerist excesses and individualist alienation of our world (amply attested to by Paul throughout the New Testament), but also crucifies the very need for a story that goes along with the desires themselves.

Therefore, we have no right to impose a law of rectitude upon other people than ourselves, and must thus live suffering the consequences (where criticisms roll out their old saw of “antinomianism”) as part of our duty taking up the cross. The end of Mr. Bennett’s commentary elaborates as such. But I think there’s a better way of getting there.

Put another way: consumerism is in many ways an iron-clad law upon our consciences, that much cannot be denied. But so are efforts to counter it: Catholic/agrarian distributism, Communism, mercantilism, the underground economy. There is entirely too much, as Luther would put it, of the first and third uses of the law in them–and absolutely none of the second. For the second, to bring us sinners to repentance, is only within us as individuals–not in our society.

Mike, thank you for expressing your concerns. If I understand you correctly, I believe we agree more than you might think. My intention in the article was not to articulate a “law of rectitude” over and against consumerism; I am not longing for us to return to the “good old days” where we have just another cultural story in the marketplace of ideas. I am merely trying to identify the current arena in which the church finds herself: a consumerist, storyless (and therefore law-centered) society. Because we find ourselves in a place where people no longer operate with a narrative, the church must do as it has always done: preach “only the Gospel of Jesus and Him crucified”. But perhaps in articulating that message, we Christians must recognize that Western society as a whole no longer even operates with a narrative as it did in modernity.

Mr. Bennett, I appreciate the response, but I am not persuaded that the terms “modernity” and “post-modernity” have any definite, concrete meaning except as pejoratives describing what the user likes of dislikes. And it still does not follow that law necessarily fills the vacuum where narratives are absent (of course, it can, but so does license, the anti-law that moralists warn about incessantly). The only thing you and I can agree on is this: the Gospel is the only hope to redeem people from idolatries and bondage of all kinds, whether they wear traditional or contemporary dress. If I forsake idolatry, I must therefore learn to live by grace, by the Word of God alone, and not by the dictates of others (meaning “culture”), save those confirmed by Spirit and Scripture. Besides, even as some people lack any historic narrative, others cling to them too closely in reaction; that is what our “culture wars” are all about in the first place. Neighborhoods, schools, churches, all reflect that now. If things were as lopsidedly rootless as you describe, we would be undergoing violent revolution right now (with real weapons, and not words). Our national-security state damn sure does not lack any narrative, I will assure you that.