Check out the mostly-related part II here, or start fresh here.

The memory verse is not always a good idea. Often it can be a shortcut toward getting a crisp, clear, self-contained biblical truth – but the search for a certain type of clarity often reflects more on our time and place as moderns than on the way the Bible means to present itself. To memorize a Proverb makes sense, but to memorize a Gospel verse often doesn’t. The former is meant to be taken as a one-sentence aphorism which doesn’t need context, but the latter is written as part of a singular whole. The most inspiring verses are often points of convergence of threads running throughout the book, and cannot be interpreted faithfully without seeing how they relate to other verses, themes of the work as a whole, the situation in which they’re spoken, and so on.

For example, take Luke 12:22-27:

He said to his disciples, ‘Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat, or about your body, what you will wear. For life is more than food, and the body more than clothing. Consider the ravens: they neither sow nor reap, they have neither storehouse nor barn, and yet God feeds them. Of how much more value are you than the birds! And can any of you by worrying add a single hour to your span of life? If then you are not able to do so small a thing as that, why do you worry about the rest? Consider the lilies, how they grow: they neither toil nor spin; yet I tell you, even Solomon in all his glory was not clothed like one of these.

God takes care of you, as he takes care of nature’s creatures, though they fret and control less. This is a passage which presents an accurate, helpful meaning on its own. We might break it down into three parts: exhortation, reason, and examples.

1. Exhortation: “…do not worry about your life, what you will eat, or about your body, what you will wear.” Simply by itself, this phrase is naked, bare, and weak. You read it and think: “yes, but I have a million things to do, a kid who needs lots of attention right now, a project at work to figure out…” A simple rule seems arbitrary, and lacks force. It needs more to it.

2. So Jesus provides a reason for the command: worrying doesn’t work. You can’t add an hour to your life, and if you can’t even do that, why bother trying to do other stuff?

3. He then uses examples to knit this principle into concrete reality: consider the lilies, consider the birds.

To tell someone “don’t worry about…” by itself doesn’t work. We often try to use these verses as almost magical formulas for invoking what they command. In the absence of the sense Jesus attaches to these commands (reason, evidence, natural world), the believer tries to follow it on the basis of Christ’s blunt authority, which acts as a cudgel on the will. Yet authority is a dangerous appeal: too much weird advice without demonstrated reason and sense engenders a loss of a trust, often. Sometimes a parent must resort to a simple “Because I said so” as a reason for something, but saying it all the time will lead the kid to think him or her capricious and arbitrary. This is one reason Jesus anchors his exhortation in concrete life.

Broadening the context further, we find Jesus preaching to the multitude, and just before speaking to his disciples of worry:

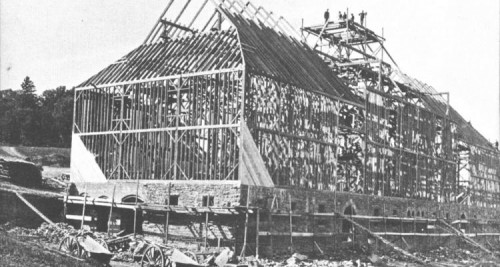

Someone in the crowd said to him, ‘Teacher, tell my brother to divide the family inheritance with me.’ But he said to him, ‘Friend, who set me to be a judge or arbitrator over you?’ And he said to them, ‘Take care! Be on your guard against all kinds of greed; for one’s life does not consist in the abundance of possessions.’ Then he told them a parable: ‘The land of a rich man produced abundantly. And he thought to himself, “What should I do, for I have no place to store my crops?” Then he said, “I will do this: I will pull down my barns and build larger ones, and there I will store all my grain and my goods. And I will say to my soul, Soul, you have ample goods laid up for many years; relax, eat, drink, be merry.” But God said to him, “You fool! This very night your life is being demanded of you. And the things you have prepared, whose will they be?” So it is with those who store up treasures for themselves but are not rich towards God.’…

He said to his disciples, ‘Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat, or about your body, what you will wear.

So “do not worry” not only has behind it the feel-good idea of God taking care of effortless lilies, but also of the fact that death can come at any moment. It also gets at the reason of why we worry – it is so tempting to think that after the next raise, after the new house, after the college fund is secure, we can say to ourselves: “Soul, you have ample goods laid up for many years; relax, eat, drink, be merry.”

One of the persistent problems with biblical interpretation I’ve seen in churches is a refusal to take the passage fully seriously. In countless Bible studies, I’ve heard comments on the lilies of the field passage, or Philippians 4:6, which roughly run: “Well, of course you have to plan for basic necessities, but what Paul’s really saying is that you shouldn’t worry spiritually…”

The context of saving food in this passage would quickly run against that. Jesus depicts the frivolity precisely of five-year plans or ten-year plans when your life may be taken at any moment. And God doesn’t just tell the man his priorities are out of order, but actively calls him a “fool!” for upgrading his granary.

I recently heard a sermon on this passage for the marriage of two people who birdwatch, and the ‘application’ was advice that they continue birdwatching. It’s a marvelous way to take the reading. It plays up the lived context in which the exhortation “do not worry” becomes more than a command, but becomes a personalized invitation to yield to the way the world works, to get on board with how God acts in it.

But merely to take away “do not worry” as a nice piece of life-advice is getting at truth cheaply, entrusting everything to raw human agency and willpower. It forgets the will’s need to be slowly, painstakingly persuaded, over years and years, not to worry by the natural world. And it overlooks the threat of capricious, unexpected death which looms over the passage. “You could die at any second anyway, so no need to worry” is hardly a Hallmark phrase. Least of all does Christ’s attempt to free us from worry mean that we should try and reach a point when we can say to ourselves, “Soul, you have ample goods laid up for many years; relax, eat, drink, be merry.” It means something else, an invitation to choose a different way of yielding up our own talents, prerogatives, and position to lean instead on God’s open-handed provision.

We cannot help but try to store up bits and pieces of wisdom, like “Do not worry,” as hedges against indecision, uncertainty, or unhappiness in life. But things are more complex: as the specter of death stalks the landowner’s improvements and retirement plans. Revelation can rarely be grasped hold of and directly appropriated, and the ‘takeaways’ we have from the Bible are often vulnerable to being recast or qualified in some way. Ideas, like physical goods, are often perishable. Someday people may know the most advanced notions of our current time to be horrible or useless and banal, and they may know some of our current theologies to be dangerously abetting or heretical. The possibility should not be anxiety-inducing, but rather the opposite: encouraging a glad open-handedness and gratefulness for the present.

In conclusion, modern discourse can be characterized by the Enlightenment search for general, literally true, and absolute principles; as well as by the skeptical, relativistic backlash against such optimism. The first force is merely a product of doing science well, but it has creeped outward and infiltrated other fields. One is everyday biblical interpretation, characterized now by a purely formalistic insistence on literal truth and non-contradiction, a disregard for textual nuance and literary form, and frequently shearing verses of their contexts in order to render them more universally applicable. Since the Bible becomes manifestly absurd when viewed in this way, the fundamentalist view helps fuel the skeptical view: both sides are looking for coherence in all the wrong places. Rules, as well, have lost their embodied, lived context, the sexual misconduct manual at a prominent college being a good example. In the realm of everyday biblical interpretation, exhortations have followed a parallel track: the more churches try to abstract exhortations like “Do not worry” from their textual and lived contexts, the more they seem like arbitrary, authoritarian decrees to those outside the church. I would say that a greater eye toward textual nuance and context and a greater concern for lived, concrete human experience can help. But we may all die this evening anyway, and the lilies of the field still lack sound hermeneutics and are doing just fine.

COMMENTS

One response to “Disembodied Truth: Memory Verses and Anxiety”

Leave a Reply

Thanks Will, this has been a great series. Very clear and more importantly, very true. The wonderful thing about unfolding the bible in context is that we discover that God treats us and develops us not as flat obeying instruments, but as human beings in all the profundity of His creation and His glory.