I first looked at a reproduction of Auguste Renoir’s A Girl with a Watering Can as a poster tacked on the wall of one of the dorm rooms in Baltimore Hall at the University of Maryland, when I was an undergraduate there in the 1970s. I was not especially impressed. The fact that it was even displayed, and prominently, in a guy’s room in an all-male dormitory, now that was a bit surprising. The most popular female hanging on young men’s walls at the time was that famous smiling, swimsuit pose of Farrah Fawcett. If I recall correctly, this was the room of the same dorm mate who regularly played modern jazz—late Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, and Maynard Ferguson—and would regularly punctuate early mornings with Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, the volume cranked all the way up, which made the presence of the obscure Renoir painting seem a bit less incongruous. He told me he had bought the print cheap at a poster sale on campus a few days earlier.

I first looked at a reproduction of Auguste Renoir’s A Girl with a Watering Can as a poster tacked on the wall of one of the dorm rooms in Baltimore Hall at the University of Maryland, when I was an undergraduate there in the 1970s. I was not especially impressed. The fact that it was even displayed, and prominently, in a guy’s room in an all-male dormitory, now that was a bit surprising. The most popular female hanging on young men’s walls at the time was that famous smiling, swimsuit pose of Farrah Fawcett. If I recall correctly, this was the room of the same dorm mate who regularly played modern jazz—late Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, and Maynard Ferguson—and would regularly punctuate early mornings with Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, the volume cranked all the way up, which made the presence of the obscure Renoir painting seem a bit less incongruous. He told me he had bought the print cheap at a poster sale on campus a few days earlier.

I was a de facto studio art major—undeclared, but taking primarily drawing, painting, and design classes—and had probably seen Girl with a Watering Can in an art history book or class, but it did not register or get remembered as something significant. The subject of the painting is as mundane as the title would indicate. A little girl with bright blue eyes and rosy lips, about four years old, in a knee-length royal blue dress with lacy white trim, her blond hair topped with a bright red ribbon, holds a small watering can in her right hand and two daisies grasped in her left hand. Renoir paints her in ¾ profile, centered vertically and horizontally, with a slight smile, gazing somewhat vacantly toward the right foreground. Her small black boots, also trimmed in white, seemed to almost hover above a hastily rendered garden footpath which covers the entire right lower quadrant of the painting. In the left foreground are flowering bushes, and Renoir has filled in the middle ground with an indistinct patch of grass, as more flowering bushes rise in the background at the top of the painting. The girl’s cheeks are modeled, and her hands and lower legs sketchily so, but she casts no shadow and, indeed, there are no distinct shadows anywhere in the painting.

Hanging in that dorm room, A Girl with a Watering Can seemed eminently forgettable, and I did forget it until the summer of 1990, when my wife, my mother, my daughter and I visited an exhibition at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. called Masters of Impression and Post-Impressionism. A wing of the building was filled with Monets, Pisarros, Cezannes, Van Goghs, and other Renoirs, along with Girl with a Watering Can, which is part of the Gallery’s permanent collection. As I came through the entryway from one gallery room to the next, I saw the painting, a modest-sized 40 inch by 30 inch canvas, on the far wall, maybe twelve feet away. Even from that distance the effect on me of astonishment and delight was immediate. Light seemed to shine out from within the surface of the canvas, shimmering and bathing the depicted scene with its own radiance. Drawing closer to the painting as I walked to the middle of the room only enhanced the effect. I sat down on the hard bench and gazed at the painting for quite awhile.

Illumination from another world seems to shine unaffectedly from Girl with a Watering Can. I felt as though I was gazing into a deep well of uncreated light. That I now know that this is the effect of Renoir’s technique—his use of a gleaming white ground allowed to show through in places, a light palette, feathery brushstrokes, lack of shadows—does not at all diminish the wondrousness of the experience, anymore than my knowing there are human footprints and a flag on the lunar surface made my experiences of moonlit nights on the sand dunes of my youth less magical, or knowing that poetry, after all, is just sounds in the air or words on paper.

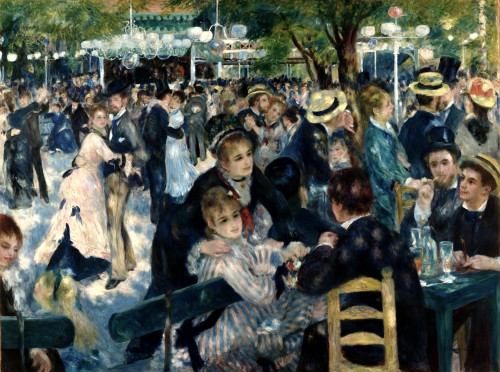

Did Renoir intend this effect on the viewers of his painting? Likely not. Renoir considered himself a painter above all; a craftsman, not an avant-garde visionary or even a rebel against contemporary standards and style. He painted because he loved painting as he loved life. His son Jean said of his father, “The world of Renoir is a single entity… an ensemble of elements which go to make one central theme, and they are bound together by a feeling of love.” And he did not think of himself as specifically an “Impressionist” painter. Yet he shared and learned from many of the same interests as other Impressionist, such as Monet, Pisarro, and Sisley. In a major period of his artistic development and output—roughly the 1870s—for Renoir, as for many of the Impressionists, the subject wasn’t really the Subject. He was trying to capture the fleeting effects of natural light on human visual perception. A Girl with a Watering Can was completed in 1876, the same year as The Reader, Dance at the Moulin de la Galette, The Swing, and others, at the height of Renoir’s impressionist period. All these succeed in fulfilling Renoir’s intentions, but I think none so well as that simple picture of a little girl in a blue dress holding a watering can.

I think Renoir caught something else he did not intend, but he caught it nonetheless; a glimpse through the ephemeral—the temporal and fleeting—into the Eternal. Biblical scholars refer to the prophetic phenomenon of a sensus plenior—a fuller sense of meaning beyond what the prophet—like Isaiah or Jeremiah—was aware of in his own words and writing. I don’t think Renoir was a prophet, not in any literal sense anyway. Yet I do think Girl with a Watering Can possesses a certain aesthetic sensus plenior—it really does cause us to experience something beyond what Renoir had in mind. Renoir simply wanted to paint what he saw. He told his son Jean, “I am not God the Father. He created the world and I am content to copy it.” But I think it is just this simplicity, this ordinariness, that actually allows Renoir’s work to be open more fully to an unseen world than more conceptual, “visionary”, or idiosyncratic art—like Picasso’s or Dali’s or Pollack’s.

Plato, in the Timaeus, called time the “moving image of Eternity”. We get the moving image part. We experience a world in ceaseless motion. Bodies move, hearts beat, the wind rushes, rivers run, waves crash, even the mountains are washed to the sea, and sunlight dapples, then all moves on. I am looking at A Girl with a Watering Can. The painting halts the moving image so I can gaze awhile at Eternity, before I have to move on. It altered me, slightly but truly.

COMMENTS

6 responses to “Ode on Renoir’s A Girl with a Watering Can: Seeing the Eternal in the Ephemeral”

Leave a Reply

Thank you, Michael. Have you been to the Barnes Foundation, now in Philadelphia? Albert C. Barnes bought 181 Renoirs! They are all on display.

I have not been to the Barnes Foundation. If I find myself in Philadelphia I will be sure to do so. 181 Renoirs would be astonishing!

Renoir is really an amazing artist! I have seen most of his paintings but I really didn’t know much especially about A Girl with a Watering Can. Really interesting post! Thanks!

Thank you, Leslie!

I can decide what’s more beautiful: Auguste Renoir’s painting or Michael Nicholson’s description ?! This was very in-depth and profound analysis. I am literally bowing to your writing talent Mr.Nicholson.

Thank you, Jordan! I am glad the piece inspired you!