1. The Net’s been a little sparse this week due, I assume, to people traveling and days off work and such, so here’s a brief week-ender with a few good links. First off, at The Atlantic, Emma Green wonders why 2014’s most religious movies were some of its worst, citing Noah (which was pretty good in our books); Exodus, which seems pretty over-the-top/plain bad; as well as Left Behind, God’s Not Dead, and Heaven Is for Real, all of which we’d probably have theological (not to mention critical) reservations about. Anyway, she diagnoses a few interesting problems of the God-movie genre in our day:

Despite their varying levels of success, these films all share one quality: They’re culturally awkward. Which suggests it’s difficult, probably impossible, to frame the “character” of God in a way that will attract a core religious audience while not alienating more secular or casually observant viewers. Ticket sales indicate there’s a strong appetite for religion-related film in America, and the best may be yet to come: Ewan McGregor is slated to star as Jesus in Last Days in the Desert in 2015. But even if the economic case for making more God flicks is clear, it’s not obvious that these kinds of movies will ever qualify as interesting art…

It’s possible that these pitfalls indicate a lack of creativity on the part of the directors and producers. But it’s more likely that filmmakers are in an impossible position when they make religious art. Believing in God is a sorting mechanism, separating those who do and those who don’t into camps with totally irreconcilable world views. In America, the cultural particularities of religion take that sorting mechanism one step further: Some may believe in God, but may not want to display that belief in their public lives. For people like this, and for non-believers, art that is centrally concerned with the existence of God may be uncomfortable or not compelling; and for those who define themselves by their faith, any circumspect approach may feel like a personal attack.

A couple of things to add to Green’s observations: first, Exodus and Noah are generically distinct from the others mentioned above. They work as epic history alongside religion, and epic history has always been subject to Hollywood distortion (see Troy, among many others). The films’ failure is first a function of the need to make a blockbuster and the ridiculous exaggerations such pressure incentivizes. It’s second a function of the movies’ failure to content itself with the texts’ oblique theology and hierophany, pushing instead into the realm of epic, direct theology and theophany. Which is why Aronofsky’s film, which rests easy with making an epic of the human experience, was pretty good. But trying to jimmy longstanding and complex theological problems creates an awkward, almost unrecognizable story, with a more-than unrecognizable God at the center of it (in Exodus‘s case, a British 11-year-old, perhaps the most egregious violation of the ‘graven images’ command since at least the Golden Calf). Which begs the question: why do writers believe viewers demand, or why do we demand, some sort of faux-religious depth in these movies? Is it a symptom of a longing for God, or a longing for some vague amorphous Thing beyond ourselves? Or simply a symptom of the impoverishment of our religious discourse? Why do we want more God in our movies than the author of Exodus felt compelled to include?

2. On the self-promotion front, reviews for DZ’s book, A Mess of Help, have been very encouraging, with Derek Sweatman, a pastor and music enthusiast in Atlanta, writing a particularly insightful review/reflection:

I knew (from the write-up on the back cover) that this book was going to drop down into the depths of music that is honest about life, that Zahl was going to shine light on universal truths, God’s truths, that lived within the lyrics of songs written by ordinary people brave enough to share their stories through song.

There was also a sense in the book that it is through music that we can find pathways not only to the stories of the musicians themselves, but also to God. That through the lyrics (and the emotions of the notes and harmonies) that something divine is happening….

The gospel is essentially the blues anyway, the story of a lover who refuses to give up on his betrayer. So when songs are written they are often shorthand for how God feels about us. Even the most prodigal (Axl?) may in fact be mimicking the prophecies and the pain of God, as he observes a creation out of sorts. And has there ever been a more bluesy lyric that “all creation has been groaning”?

The grooves that encircle the label on the record are the scars that give voice to artist’s life and experience. They make the noises of pain and hope, of betrayal and redemption. They do not come lightly, but with a cost. And not just the cost of losing a bit of yourself through exposing your heart through music, but the cost of personal exegesis, followed by the revealing of those discovered truths, no matter how ugly.

(from xkcd)

3. NPR had a readworthy, if a little zeitgeisty, piece on Jesus as a foodie. A teacher at a wine school talks a little about winemaking in the near-East of Jesus’ day, and (spoiler alert) it almost certainly was alcoholic, ht EB:

Alsop stresses that his interpretation is subjective. As an example, he cites Christ’s offering of bread and wine as his body and blood during the Last Supper.

“He’s saying, spiritually, take me inside you and let my spirit suffuse your spirit, but naturally he does that through these wine and food metaphors,” Alsop says.

When asked if he thinks Jesus would have preferred red or white wine, Alsop doesn’t hesitate.

“I’d like to think that Jesus was a red guy,” Alsop says. “I don’t know why. I guess it’s just my own personal desire to see it that way.”

We’ll never know, of course. McGovern says the Romans preferred white wine, but according to inscriptions found on ancient bottles and casks, most wine from the Holy Land was, indeed, red.

(from Jawbone)

4. Salon.com published, over the holidays, a piece about the intellectual problems with religion, mostly Christianity. We almost wrote a long-winded rebuttal to it (it’s highly rebut-able), but it’s actually a much better study in how closed-minded righteous indignation breeds more closed-minded righteous indignation, and people rarely change their minds. I certainly found myself becoming a less Christan (though more dogmatic!) person while reading it, which isn’t good for anyone. You also have to imagine that a lot of brilliant agnostics/atheists read these things and feel like I would reading Joel Osteen. Anyway, as more of these insipid, unoriginal pop-atheism pieces come out (and God knows we Christians have foisted on the world more than our share of that kind of thing), it’ll be interesting to see how much perspective – as well as space for credible, constructive debate on both sides – can be maintained.

5. For a much better Christianity and culture article, check out “Are Evangelicals the New Liberals?” by Samuel Loncar, a review of David Hollinger’s After Cloven Tongues of Fire, a meditation on the influence of Liberal Protestantism, and Molly Worthen’s brilliant Apostles of Reason. The article takes the definition of Evangelicalism a little too much for granted, it skips over some of the nuances of biblical inerrancy/infallibility, and it seems a little unfair to Evangelicals, but still, there’s some fascinating stuff in there, ht SZ:

The secularization thesis was always wrong in positing the inevitability of religious decline. But Hollinger and Worthen, read in the wider, transatlantic context of Liberalism as the story of Christianity’s reconciliation with (or destruction by) the modern world, reveal how taut are the wires that connect Christianity and modern life: tight enough for a delicate balancing act, yet ready to snap at any moment. They show not only that America has been a central site of the drama of Christianity accommodating the Enlightenment, but that Evangelicals are themselves the last great test of whether conservative Protestantism can retain its identity as it moves from the periphery of culture towards its center, or whether Nietzsche was right after all: God is dead, and Americans are simply the last to hear the news.

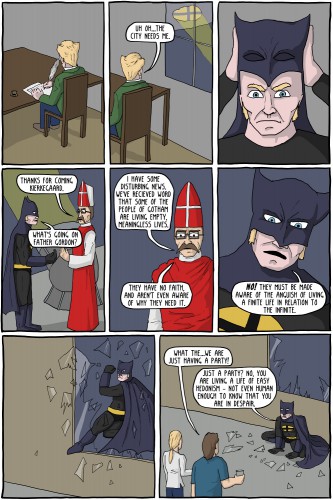

6. In humor, RIP The Low Churchman’s Guide to the Solemn High Mass, a series of brutal criticisms of Roman Catholic inspired “Ritualism” which satirizes its speaker’s Puritanical paranoia. A must-read for anyone in a liturgical church or with an ecclesiology hobby. Also on the nerdier side, Existential Comics presents Kierkegaard’s/DC Comics’s The Dark Knight of Faith, with a handy guide to the references on the comic’s homepage.

Bonus Links: The Onion strikes another gloomy note with its self-explanatory Christmas headline, “Family Receives 38-Piece AstraZeneca Assorted Pill Sampler“. Also in Christmas news, with three days left in the season, the NY Times notices some conspicuous consumption/self-gratification around Christmastime, tracing the “wealfie” trend. And, although some of our staff have sworn off examining the bound will’s problematic relation to New Year’s resolutions, our friend Tullian Tchividjian’s deconstruction of resolutions on MSNBC’s Morning Joe is well-worth a look. Happy 2015.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply