This wonderful reflection comes from Emily Stubbs.

This wonderful reflection comes from Emily Stubbs.

Often times we self-justify through the things that we associate with and claim as part of our identity: I am a vegan, I am a Phi Mu, I am a fellow at Christ Church, and I wear Led Zeppelin t-shirts from Goodwill and earrings that I bought from a Peruvian man (hypothetically speaking). While, indeed, we attempt to prove our identity by vainly clinging to other people, things, ideas, organizations, etc, we also self-justify through the things that we turn away from. My identity as an independent, autonomous human being is equally dependent upon what I distance myself from as it is what I attach myself to.

I dissociate with Taylor Swift. I dissociate with Starbucks. And I totally dissociate with anything that is not free-range, organic, and cold-pressed. What we eschew can, at times, be equally as absurd as what we link ourselves to. For example, how would anyone take me seriously as a vegan if I ate an order of french fries from McDonald’s everyday? And, seriously, I can’t listen to Taylor Swift’s music because it threatens my identity as a music snob with sophisticated taste. Even Starbucks is too mainstream and thus threatens my identity as a counter-culture, progressive, and independent thinker (read: hippie, hipster, townie, etc). More seriously, however, we reject things that remind us of our own frailty, vulnerability, and even mortality.

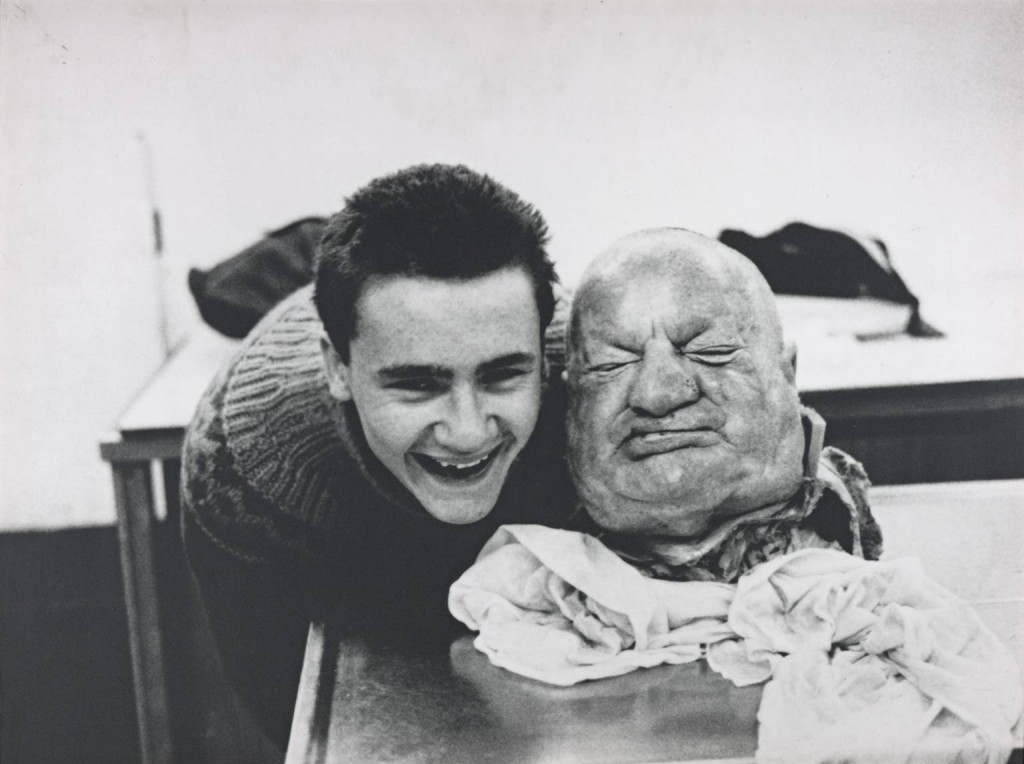

And to that end, on the most fundamental level, we do everything in our power to reject and discard things related to our own bodies, such as vomit, blood, and, importantly, corpses. To be sure, vomit and rotting corpses do not exactly smell like daisies, but why do we go the extra mile and hire morticians to put makeup on our deceased loved ones at the funeral home? Why do we feel so scandalized when looking at Damien Hirst’s vitrines housing embalmed animal corpses when they pose no threat of stench or decay? For the Bulgarian-French philosopher Julia Kristeva, the root cause of the repulsion and anxiety we experience in the face of these objects is brought on by an encounter with the abject, which, by definition, is that which endangers our carefully constructed identities. As she says in Power of Horror: An Essay on Abjection:

It is thus not lack of cleanliness or health that causes abjection but what disturbs identity, system, order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules. The in-between, the ambiguous, the composite. The traitor, the liar, the criminal with a good conscience, the shameless rapist, the killer who claims he is a savior. . . . Any crime, because it draws attention to the fragility of the law, is abject, but premeditated crime, cunning murder, hypocritical revenge are even more so because they heighten the display of such fragility.

Kristeva argues that the abject is not an object but rather it is that which threatens to undo the border that demarcates me (the Subject) from the rest of the world, that is, everything outside of me. The abject reminds us of who we really are–mortal, vulnerable, (literally) porous human beings. While, indeed, my skin encases and protects my body, it is not impenetrable. Sweat and blood are a scary reminder of that fact. And there is the corpse, which, for Kristeva, represents “the utmost of abjection.” Because the corpse is inanimate, hence dead, it is no longer the Subject; moreover it hints at the moment when a human ceases to be, when the Subject again assumes an undifferentiated ego-less state. At the same time, the corpse cannot be entirely divorced from the Subject because just a few minutes, hours, days ago, it was the living, breathing Subject. The corpse, therefore, signifies and portends the collapse of my own selfhood and distinctiveness, and the decay that inevitably ensues is the explicit, physical confirmation of that fact. Abjection, thus, is a process of individuation and exclusion; it is our ongoing attempt to deny and rid ourselves of all things that bring us in contact with the abject, such as the corpse. We dissociate and reject in order to assuage fears of our own frailty.

Through the process of abjection, we work tirelessly to broadcast our autonomy and deny the facts of our human-ness. And this basic refusal of my own human condition grows and manifests itself in all areas of life. Left to my own devices, I insist on my own justification. Running from the fact of my frailty, I find myself stuck in a web of rules I have created for myself. No meat, no dairy, no Starbucks, no Taylor Swift. It is hard to keep everything straight and really a bit tiresome. Despite even our most valiant efforts, however, the ramparts of our self-justification are equally as porous as our skin. All it takes is one stab to see the blood and sweat that lie just beneath the surface of my self-justification.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply