Spoiler alert: There’s a knee-slapping section toward the end of PZ’s Panopticon: An Off-The-Wall Guide to World Religion in which the author ranks “religions that are not called religions.” He gives us a tongue-in-cheek US News and World Report-styled guide to which of them (Sex, Power, Ideology, etc) will serve a person best, which has the longest shelf-life and the most return. I don’t want to give away too much, but I will tell you the one that comes in last and therefore qualifies as the most consistently disappointing object of worship: Things, or Possessions. Unlike, say, family, “these get old the moment you get them.”

‘Duh!’ you say, ‘No need for a post about the hollowness of materialism, Captain Obvious.’ Still, like so many other things in life, the knowledge that something can’t deliver the satisfaction it promises (or Madison Avenue promises) is rarely enough to make us stop looking to it to do so. I got a fresh reminder recently.

God bless the publishing industry. Like the music biz, people who work in books have had to work double-time for our dollars this past decade. If the downside of online domination is (in order from most painful to least) the extinction of the quirky local bookseller, the lost pleasure of browsing, and the ever-creeping knick-knack annexes in Barnes and Noble, then the upside, other than the obvious economic one, may be the upsurge in ‘deluxe editions.’ I mean, just take a look the package they came up with for the Breaking Bad: The Complete Series set. It’s absurd. Amazon has become “completist’s” paradise! The standard for these collector’s editions has been ratcheted up unbelievably high, and with it… the ensuing sense of emptiness.

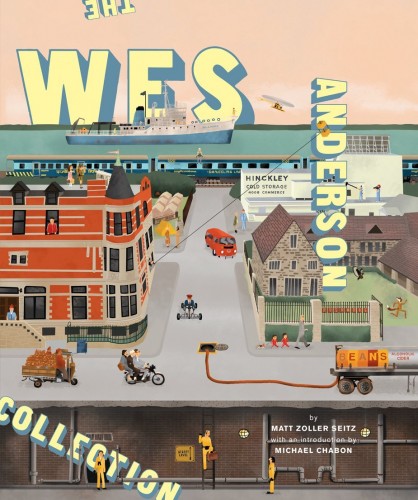

My current case in point: Matt Zoller Seitz’s The Wes Anderson Collection, which arrived in the mail last week. I had been waiting for it for close to a year, such is my admiration for and interest in both the people involved. When it came, I did a bit of a double-take. I was not expecting something so beautiful and substantial–the price I paid certainly didn’t indicate the level of quality. Ten years ago this book would have cost $80, not $25. But I digress. The point here is that if anything could scratch that materialist itch in me, The Wes Anderson Collection is that thing. It is a treasure! And yet there I was, later that evening, trying to find a deal online for the new boxed set from The Band… I believe it was Joss Whedon who recently tweeted, “Everything is a drug. Family, art, causes, new shoes… We’re all just tweaking our chem to avoid the void.”

My current case in point: Matt Zoller Seitz’s The Wes Anderson Collection, which arrived in the mail last week. I had been waiting for it for close to a year, such is my admiration for and interest in both the people involved. When it came, I did a bit of a double-take. I was not expecting something so beautiful and substantial–the price I paid certainly didn’t indicate the level of quality. Ten years ago this book would have cost $80, not $25. But I digress. The point here is that if anything could scratch that materialist itch in me, The Wes Anderson Collection is that thing. It is a treasure! And yet there I was, later that evening, trying to find a deal online for the new boxed set from The Band… I believe it was Joss Whedon who recently tweeted, “Everything is a drug. Family, art, causes, new shoes… We’re all just tweaking our chem to avoid the void.”

The sweet irony of this little fable is what happened next, though. I opened the book that night and started reading. One sentence into novelist Michael Chabon’s introduction and I was hooked. In fact, I was more than hooked. I was understood. I even felt ministered to. Maybe you will be too:

The world is so big, so complicated, so replete with marvels and surprises that it takes years for most people to begin to notice that it is, also, irretrievably broken. We call this period of research “childhood.”

There follows a program of renewed inquiry, often involuntary, into the nature and effects of mortality, entropy, heartbreak, violence, failure, cowardice, duplicity, cruelty, and grief; the researcher learns their histories, and their bitter lessons, by heart. Along the way, he or she discovers that the world has been broken for as long as anyone can remember, and struggles to reconcile this fact with the ache of cosmic nostalgia that arises, from time to time, in the researcher’s heart: an intimation of vanished glory, of lost wholeness, a memory of the world unbroken. We call the moment at which this ache first arises “adolescence.” The feeling haunts people all their lives.

Everyone, sooner or later, gets a thorough schooling in brokenness. The question becomes: What to do with the pieces? Some people hunker down atop the local pile of ruins and make do, Bedouin tending their goats in the shade of shattered giants. Others set about breaking what remains of the world into bits ever smaller and more jagged, kicking through the rubble like kids running through piles of leaves. And some people, passing among the scattered pieces of that great overturned jigsaw puzzle, start to pick up a piece here, a piece there, with a vague yet irresistible notion that perhaps something might be done about putting the thing back together again.

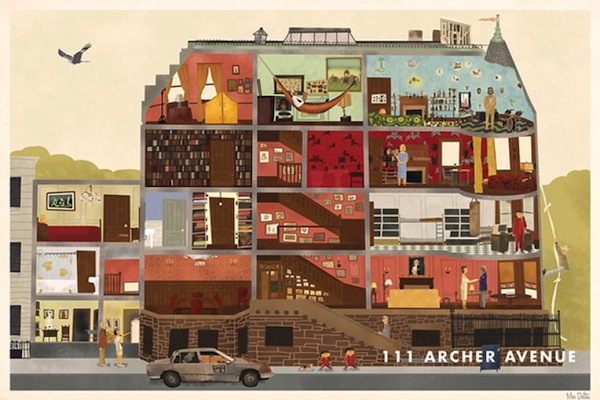

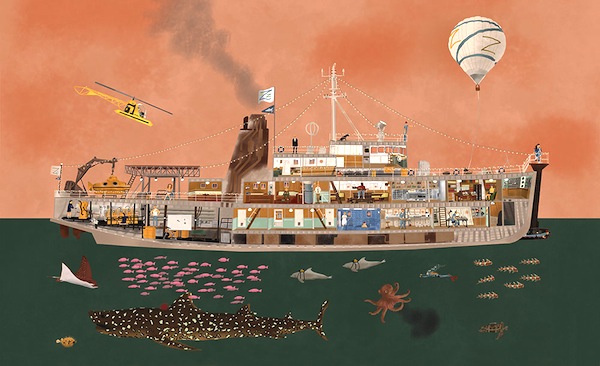

Two difficulties with this latter scheme at once present themselves. First of all, we have only ever glimpsed, as if through half-closed lids, the picture on the lid of the jigsaw puzzle box. Second, no matter how diligent we have been about picking up pieces along the way, we will never have anywhere near enough of them to finish the job. The most we can hope to accomplish with our handful of salvaged bits—the bittersweet harvest of observation and experience—is to build a little world of our own. A scale model of that mysterious original, unbroken, half—remembered. Of course the worlds we build out of our store of fragments can be only approximations, partial and inaccurate. As representations of the vanished whole that haunts us, they must be accounted failures. And yet in that very failure, in their gaps and inaccuracies, they may yet be faithful maps, accurate scale models, of this beautiful and broken world. We call these scale models “works of art.”…

The man is almost channeling CS Lewis, am I right? Chabon’s words reminded me of a recent article that Alain de Botton wrote for the Wall Street Journal on “Art as Therapy”:

If art is to deserve its privileges (and it does), we have to learn how to state more clearly what it is for and why it matters in a busy world. I would argue that art matters for therapeutic reasons. It is a medium uniquely well suited to helping us with some of the troubles of inner life: our desire for material things, our fear of the unknown, our longing for love, our need for hope.

We are used to the idea that music and (to an extent) literature can have a therapeutic effect on us. Art can do the very same thing. It, too, is an apothecary for the soul. Yet in order for it to act as one, we have to learn to consider works through more personal, emotionally rich lenses than museums and galleries employ. We have to put aside the customary historical reading of works of art in order to invite art to respond to certain quite specific pains and dilemmas of our psyches.”

This is, of course, very similar to what we mean when we talk about the abreactive potential of art. It can get us in touch with emotions we are afraid to feel (but need to), or to paraphrase Walker Percy, tell us things we already knew but didn’t know we knew.

Which brings me back to Wes Anderson (and myself) and, maybe, the hand of God. It’s not a coincidence that I’ve found myself absorbed in the book this week and wanting to re-watch the films yet again, pining for Grand Budapest and laughing at the SNL horror parody (below). Yes, they’re familiar and, yes, they’re funny and visually absorbing, but why now? The answer I’m pretty sure has to do with death. Having just attended the fourth funeral of a close family member in the past twelve months, the subject is on my mind, probably in more ways than I’m aware of, and as whimsical as they may be, Wes Anderson’s films are all consumed with death and loss–of a marriage, of a parent, of a loved one, of a tail. Not exactly a popular subject, especially for the Anderson demographic, but one that he approaches with considerably more open-endedness (and grace) than most of his more cynical peers. Chabon writes:

Grief, at full scale, is too big for us to take it in; it literally cannot be comprehended. Anderson understands that distance can increase our understanding of grief, allowing us to see it whole. But distance does not—ought not—necessarily imply a withdrawal.

He’s right–the emotional remove doesn’t turn these films clinical, nor does the overriding sense of grief render them morbid. Quite the opposite. It makes the mending of the broken pieces, however incremental the process may be, that much more breathtaking. Remember, despite their hip(ster) reputation, all of his films have what can honestly be called happy endings. And instead of telling us how to feel about that, Wes gives his audience the space to come their own conclusions, both heart- and head-wise. It makes for a rich viewing (and re-viewing) experience, to say the least.

Speaking of endings, the book itself did not satisfy, nor was it meant to. But it did bring me, for a moment, face to face with the futility of my attempts to engineer wholeness. More than that, though, it provided some comfort in a time of loss, and the sense that death is as much a beginning as an end. I know of only one other book like it.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gSEzGDzZ1dY&w=600

COMMENTS

2 responses to “Coffee Table Maps to Lost Wholeness (Courtesy of Wes Anderson)”

Leave a Reply

Beautiful. Thank you David.

Wes Anderson, Michael Chabon and DZ…three favorites of mine. What a combination! Thanks DZ.