This reflection comes from Chelsea Batten.

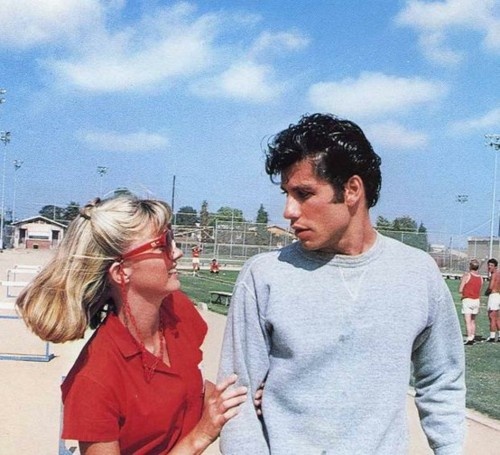

I probably shouldn’t have gone back to his place. But I was leaving the next morning, and I didn’t want to leave him a moment before. A proper Christian lady would say that she regretted staying the night at his place.

But I don’t regret that. What I do regret is that we turned on a movie. That we spent the evening watching it, before making out for a few brief minutes and then falling asleep on his couch.

He’d made me feel more special than anybody ever has, before or since. Every five minutes his manners, his consideration, his kindness took me back, had me thinking, “Who the hell is this guy?” (That’s even what my mom said, when I told her about him. Minus the expletive, of course.) My regret is that I didn’t spend the time in between getting to his place and leaving it searching for the answer to that question.

Yet another magazine cover story came out, last summer, saying “Guess what, guys? Facebook doesn’t make us statistically happier…in fact, it’s starting to look as though it makes us unhappier.”

I’m sorry–didn’t we hold those truths to be self-evident? If I had a dime for every conversation with a disgruntled IRL friend who complains about how perfect everyone tries to appear on Facebook…well, I could at least pay for a subscription to the magazine that re-explained this to me.

My friend Dan compares studies like these to the ones about coffee. Every few months, some authority comes out saying something like, “Coffee might not be all that bad for you,” or “Coffee is ruining you.”

The thing is, Dan says, we will always want to be told why we should stop drinking coffee, because we’re never going to stop. This kind of information is the only thing that slows down our consumption enough to possibly save our lives.

“People with the most amount of privilege practice the least amount of discretion when it comes to excess of various kinds,” he said, just like that. “It doesn’t mean they consume the most–it means the people who have every opportunity not to let something consume their lives, still do.”

Shortly after that magazine cover story, Vimeo featured an animated film called “The Innovation of Loneliness.” I watched it for something I could love to hate, looking for proof of my case. Instead, I found myself in the dock.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c6Bkr_udado&w=600]

“We’re sacrificing conversation for mere connection,” says filmmaker Shimi Cohen. “What is the problem with conversation? Well, it takes place in real time, and you can’t control what you’re going to say.”

Suddenly, the nebulous shame I felt about going to that guy’s house came into sharp focus. I hadn’t done anything I felt guilty for; I hadn’t treated him badly, or been treated badly myself. Everything had been lovely and nice and sweet and romantic. But I hadn’t treated him like an actual human being. I was so focused on enjoying our connection until the moment I had to leave, that it never occurred to me to start a conversation with him.

Conversation is revelatory. It doesn’t kill connection; it consumes it. It leaves us wanting more, and sometimes more of what we want isn’t there.

Facebook, however—and social media in general—isn’t for conversation. It’s for making connections. That’s why it’s addictive; that might even be why it’s good. Think of all the lonely people who felt like there was nobody out there who liked or understood them and, suddenly, they’ve found a fleet.

I think connection is exactly what C.S. Lewis had in mind, in his quote about the moment friendship is born—“when one person says to another, ‘What! You too? I thought that no one but myself…’” E.M. Forster, in his foreword to A Passage to India, urged readers, “Only connect.”

I think connection is exactly what C.S. Lewis had in mind, in his quote about the moment friendship is born—“when one person says to another, ‘What! You too? I thought that no one but myself…’” E.M. Forster, in his foreword to A Passage to India, urged readers, “Only connect.”

I don’t think he was anticipating that future generations would take that advice literally. For that matter, I don’t think C.S. Lewis guessed how many friendships would be stillborn after that first thrilling moment.

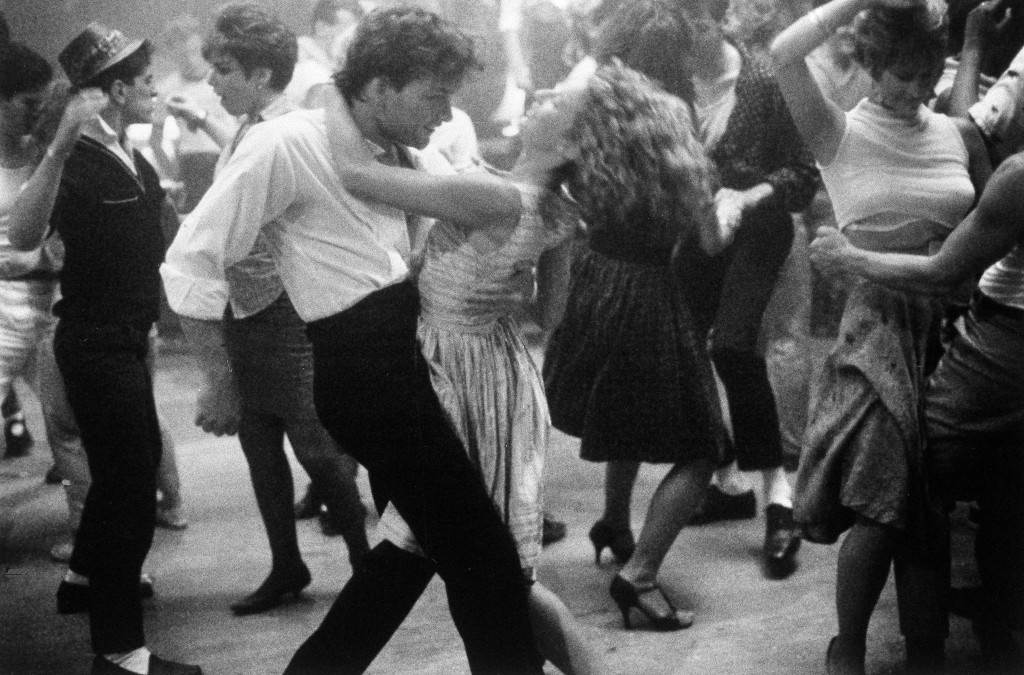

The wonderful, addictive thing about Facebook and summer flings alike is that they allow us to keep a relationship right there, poised on the knife-point of connection. Both kinds of relationships are instant, intensely felt, and presuppose a very short shelf life. The connection is flash-frozen in time, a poignant memory unthreatened by any hopes or expectations.

Of course, social media isn’t the only place where we keep relationships pruned to the point of connection. There are many of us that “connect” so well with certain people—in church, at the gym, on opposite sides of the Starbucks counter. Seeing them provokes this ethereal, unspoken thrill—my eyes meet theirs, across the counter or the conference table, and I know, without words, that they’re feeling the same way as me.

Connection is magical, and a life in search of it transforms into a montage of meet-cutes—the ringing thrill of discovery, the moments when eyes meet and hearts leap…and end scene. The train pulls away, the piano falls, I close my browser window, warm with the feeling that I’m not alone. Why ruin that feeling with a conversation?

I was so excited to connect with a smart, lovely person over the best things about both of us–that language fascinates us, that we care about our friends even though we feel a little out of place with them, that what makes us happiest about being with someone is the opportunity to make them feel happy.

Of course, we talked some. But our talking consisted largely of one person saying something, and the other saying “Yeah, me too.” It felt so good to say those words. I didn’t want to ruin it by going into deeper detail, or asking other things that might make us feel less connected. After all, I was leaving the next morning.

According to Shimi Cohen, this is the kind of false premise over which simple connection is forged. It isn’t a lie (usually)…it’s simply a carefully edited truth about myself. I call it being the best version of myself. I think I’m protecting another person from my baggage regarding relationships or what have you; what I’m really protecting is myself against the damp influence of reality, believing that connection is enough to keep me warm.

“But,” Shimi Cohen says, “the opposite is true. If we are not able to be alone, we’re only going to know how to be lonely.”

The animated video illustrates how technology makes it possible to forge the kind of self that we think people want to connect with–at least, the people that we’d like to be connected to. It’s not a lie; it’s just edited. It might be easier if it were just a lie; the effort of marketing ourselves with some semblance of truth takes a lot of time, time that we aren’t spending having conversations wherein, as in Mr. Cohen’s earlier quote, anything might be revealed.

A waiter spills a drink in your lap, and suddenly the person you’re talking with knows a) how you respond to bad luck, b) whether you value things over people, and c) whether you are really the egalitarian you claim to be.

That person might not leave you alone forever, after that. But the connection you started with will probably be weakened–the connection, that is, over the belief that you’re amazing. That’s a connection that it hurts to lose.

When it came down to it, I wanted to leave him still thinking I was amazing. And I wanted to leave still thinking he was amazing. I didn’t want to get on a plane feeling embarrassed that I’d felt connected to this guy. So I didn’t give him a chance to prove me wrong. I kept it light. I didn’t get to know him too well. I might not have treated him badly, in the usual sense, but I did use him, for my own purpose of feeling good.

I wonder what’s worse: being alone with your memories of fond connection with someone? Or being with someone whom you don’t feel as connected with, as you used to?

Maybe it depends on the person. But maybe it’s not that subjective. Maybe the right thing is to always treat people like the people they are–seeking to know them as whole persons, finding the points where you don’t connect and striving to go deeper until maybe, unexpectedly, you do unearth a connection. Or, barring that happy outcome, accepting and honoring them by seeking to know even if you can’t understand.

I’ve been gone for some months, and we haven’t talked. Which is fine–we didn’t say we were going to. But since we didn’t talk, all I have to remember him by is the wonderful way he made me feel. It’s a nice memory, but it’s a lonely one.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7CAYFIpi89k&w=600]

COMMENTS

4 responses to “Lessons Learned from a Summer Fling”

Leave a Reply

Chelsea – what a wonderful piece. Hits home for summer flings, facebook and everything in between. Thanks

That’s very kind, Will. Thank you for reading.

Chelsea…..so much food for thought here. Writing like this is why I so often find myself visiting Mbird.

This is a very intriguing post, one that will pondered well beyond the first reading. For me, there’s an element not considered here: the superficiality of much face-to-face “connection” in social situations. I think one reason people are drawn to online media is that there is a distance that creates a sort of safety buffer that sometimes enables us to be MORE authentic than we might be in person. I’ve often been told that I’m “intense” – (translation “too intense”) — and I know from experience that most people find that uncomfortable. Based on my own experience, it seems it’s a trait that is a bit more palatable in writing, whether in print or online. Perhaps it’s a form of being socially inept, but maybe not. Maybe it’s simply an impatience with chit-chat that is not about what it’s about. Thanks for a thought-provoking discussion!