If I could do it all over again, I would have chosen tennis as my sport. It’s not that I regret my experiences in team sports like baseball and water polo, or that I don’t see how much more potent they are than individual sports when it comes to making memories and teaching larger-life-lessons. In fact, I look forward to living vicariously through my kids’ involvement in those things as much as the next guy. And I often wonder if my swimming “career” in high school and college, with all its unavoidable performancism and psychological intensity, led more or less directly to my embrace of grace in my 20s. Still, tennis is the sport I find most captivating and satisfying as an adult, both as a spectator and participant. Beautiful even. If I’d only started earlier!

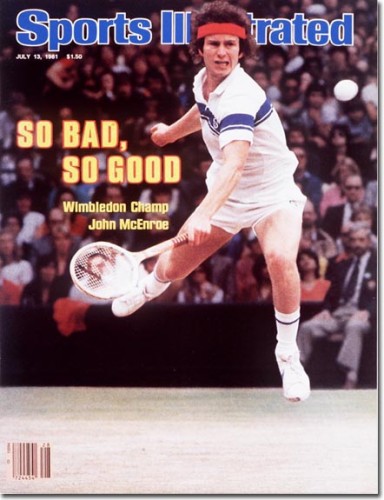

A large part of the game’s appeal, if I’m being honest, has to do with John McEnroe. Normally, given a viewing option, I’ll choose scripted television over sports. Maybe it’s due to moving so frequently during childhood that fan loyalties never had a chance to codify. Maybe it’s because I was raised by a man who I’m pretty sure couldn’t tell you how even the scoring in football works, bless his heart. Maybe it has to do with some lingering (at this point, pretty silly) resentment of teenage jock culture. Maybe, as a former swimmer, I’ll always associate sports with stress and scrutiny, I don’t know. Probably all of the above. Whatever the case, I tend to change the channel when a game comes on. Unless it’s tennis. Correction: unless it’s tennis and John McEnroe is in the booth. Is there a better commentator in sports? Sharp, passionate, incredibly opinionated, unpredictable, funny, unafraid to drop a value judgement or three–pretty much a fully realized human being.

A large part of the game’s appeal, if I’m being honest, has to do with John McEnroe. Normally, given a viewing option, I’ll choose scripted television over sports. Maybe it’s due to moving so frequently during childhood that fan loyalties never had a chance to codify. Maybe it’s because I was raised by a man who I’m pretty sure couldn’t tell you how even the scoring in football works, bless his heart. Maybe it has to do with some lingering (at this point, pretty silly) resentment of teenage jock culture. Maybe, as a former swimmer, I’ll always associate sports with stress and scrutiny, I don’t know. Probably all of the above. Whatever the case, I tend to change the channel when a game comes on. Unless it’s tennis. Correction: unless it’s tennis and John McEnroe is in the booth. Is there a better commentator in sports? Sharp, passionate, incredibly opinionated, unpredictable, funny, unafraid to drop a value judgement or three–pretty much a fully realized human being.

I’ll never forget a US Open match a few years ago when McEnroe got bored with the action and took the opportunity to outline his theory about how doubles is an inherently lesser game than singles, how nowhere near as much skill is involved in becoming a good doubles player than a singles one, and anyone who claimed otherwise was fooling themselves. Whatever you make of the controversial contention, it cut through the practiced phrasing and talking points in an incredibly refreshing way. Usually those humanizing moments are reserved for the field of play rather than the booth itself.

That’s all by way of an elaborate introduction to the most fascinating (and mockingbait-ish) sports article I’ve read since the one on Urban Meyer. I’m referring to James McWilliams’ piece for the increasingly terrific Pacific Standard, “John McEnroe and the Sadness of Greatness.” It might as well be called “John McEnroe and the Curse of the Law”, as it’s a jaw-dropping example of what happens when someone actually achieves momentary perfection (fulfills the Law) and the explosion-inducing pressure that builds up when flawlessness becomes the only acceptable outcome in a person’s life. Take a gander:

In the summer of 1984 John McEnroe beat Jimmy Connors in the Wimbledon finals 6-1, 6-1, 6-2. The match was, as one British journalist called it, “the most imperious victory in the history of tennis.” McEnroe made only three unforced errors. Seventy-eight percent of his first serves were in. Ten were aces. After a couple of those aces, Connors looked down in confusion, as if his shorts had dropped to his ankles. All McEnroe could say about the match was that the ball looked like “a cantaloupe.” It was as close as a tennis player had ever come to achieving actual perfection.

And that was the problem. The awful irony of McEnroe’s victory over Connors was that—in its near perfection—the performance couldn’t be sustained beyond the moment. The victory thus marked a year during which McEnroe would gradually sense what perhaps only exceptional athletes can sense: the moment of his own demise. The result of that realization for McEnroe was, McEnroe being McEnroe, an explosive moment of personal recognition, manifested, naturally, in an infamous tantrum.

Sports psychologists are quick to identify the emotional risk inherent in the athlete’s quest for perfection. They write with painful formality, noting such things as how “the extreme orientation that accompanies perfectionism is antithetical to attaining positive outcomes.” McEnroe, as he had a way of doing, had taken that “extreme orientation” to a new extreme and, upon realizing the temporality of his accomplishment, went ballistic on a Swedish tennis court in a way that was more terrifying than entertaining. The incident, thanks to YouTube, has amassed a sort of cult following. It deserves a re-visitation because, among other things, it offers rare insight into the raw emotion that marks the inevitable pain of being great…

Blood was spilled all over in 1984. And not just on Connors. McEnroe won 78 of his 80 matches that year. It was an astounding accomplishment. For all intents and purposes, a player couldn’t imagine having a better year. Yet, for all his success, the tour was sustained by forces horrible and dark. McEnroe, winning match after match, spent the year getting angrier and angrier, cursing judges, mocking fans, and pacing the court as if it were the common room of an asylum. This anxiety culminated at the Swedish Open. It came in a match he eventually won against native son Anders Jarryd, and it came in the form of an upper-shelf outburst that would mark his inevitable decline in tennis greatness at the professionally precarious age of 25…

As an unrelated aside, I’m reminded of that great passage in Grace in Addiction in which John Z writes, “We live in a culture so besieged with anger that it can be very difficult to imagine life without it. And so we try to justify our anger. People talk about things like ‘healthy anger’ and ‘channeling anger in a productive way.’ Remember John McEnroe, who was famous for his ability to play better tennis when he was angry? Alcoholics Anonymous wholeheartedly parts ways with this train of thought. In AA there is no such thing as ‘healthy anger.’ It is all bad; it is always toxic. In short, you are not John McEnroe.” But back to the match in question:

When clinical psychologists evaluate patients with anger issues they try to ascertain if an outburst was “within a normal range of magnitude.” McEnroe always berated himself a little bit when he cheated his own greatness. Under such circumstances his normal range of magnitude was modest. He’d throw his racket or yell at a fan or declare himself to be a worthless human being. But when an umpire with coke-bottle glasses was the one cheating McEnroe’s greatness, his normal range of magnitude became infinite. Given the nature of his game, given the nature of being John McEnroe, how could it have been otherwise?

His entire life was spent internalizing the dimensions of a tennis court and, in turn, fine-tuning his body to respond to those dimensions with tiny chops and hacks. His body knew tennis the way a falling ball knows gravity. The reality of McEnroe’s tantrum in Sweden was that, as he raged, he knew, by whatever intuitive calculus one knows such things, that it would never again be so perfectly awesome to be John McEnroe…

It’s a terrifying prospect to contemplate—that a great athlete can be witness to, and feel the full weight of, the precise moment of his fall from greatness. But when that judge in Sweden called McEnroe’s serve out, I suspect he changed the lines for John McEnroe, and McEnroe, much like George Washington checking his pulse at the moment of his death, knew it as well as he knew every inch of the court.

Here’s the infamous clip, which the article calls “almost Shakespearean.” Apparently it is even studied in acting circles by those preparing for roles that involve public breakdowns:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C8Nyc9jzSDg&w=600

Now I guess I could wrap things up here with a nice Matthew 5:17 bow. Or talk about how this same dynamic plays out in terms of Christian sanctification, how perfectionism is just as deadly if not more so than its opposite, etc. Instead, here’s a theory of my own: the key to McEnroe’s appeal is that he’s so free. Free to be honest, free to criticize, free to improvise, to laugh (at himself), to be wowed, to be enraged, yes, to love (make no mistake, this man loves tennis). Granted, he’s always lacked a filter. Yet I wonder if McEnroe’s freedom comes, at least in part, from being so intimately acquainted with the cost of perfection, his firsthand knowledge of how it doesn’t bring peace, and how the game is only worth playing if you enjoy it. Sure, he’ll always be hyper-competitive, and he’ll always be a little petulant–he’ll always be McEnroe, thank God–but my suspicion is that what accounts for his contagious devotion to the sport of tennis, why he’s so happy to serve as the world’s top “ambassador for the game” (his favorite phrase), is because it beat him. And that defeat, in its decisiveness, released him from the burden of perfection he had placed on both himself and the world around him–and once they had been cast off, all that remained was affection.

Then again, maybe he’s just a dude from Queens with amazing racquet skills and a big mouth. And if anyone wants to argue that call… they cannot be serious.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “The Precise Moment of John McEnroe’s Fall from Greatness”

Leave a Reply

I like the post but completely disagree with the James McWilliams’ piece. He probably never saw Mac play. The US open final that year was even better when he destroyed Lendl. Every time Lendly missed his first sever, Mac would walk inside the baseline about 2 feet to return his second serve!! Chip and charge, volley point Mac. It was so intimidating and showed supreme confidence. The reason he could not sustain it was they allowed the big racquets in and he started getting overpowered. Look at your pic–Dunlop woodie. He had such touch with that racquet! His game was all angles and touch and intelligence and the big raquets destroyed it. I agree with you that he was hypnotic to watch when he was on his game.

The beauty of his game is one of a kind. I don’t care to watch any other player (except perhaps Borg), with their cookie cutter form and ‘hit everything hard’ style. Mac’s racquet appeared to be an extension of his arm, his movement and touch were unmatched, and he played the game in a style that I suspect the game’s founders had in mind in the beginning. I don’t know about his greatness haunting him, or perfection’s cost or affect on an athlete. I just know when I go on-line to watch tennis….it’s Johnny Mac. Every time..

[…] time Mockingbirds will know — David Zahl loves Pickleball and tennis great John McEnroe. Here’s a [profanity laden] interview with John McEnroe where he shares his opinions on […]