I’ve just begun reading When God Talks Back, by T.M. Luhrmann, which is a psychological and sociological study, of the life of American Evangelicalism. Luhrmann looks with sober, even compassionate, appraisal within a Vineyard church in her community, where she spends two years “studying” the psychological dimensions of a faith community, of “having a personal relationship with Jesus Christ.” If you’re familiar with the Evangelical trappings, she covers the whole bit–the coffee lead-in to worship, the very long worship as an individualized space to invite the Spirit, the “teaching” rather than the sermon, phrases like “God really showed up this morning.” She does this without a note of condescension, but with even-keeled consideration, a noteworthy attribute when you recount most “outsider”-perspectives.

And so I was given a little bit of clarity into this guns-down approach with two of her articles that were released in the last month, both from the New York Times. The first one has to do directly with prayer. Using psychologist Daniel Kahneman‘s two notions of thinking (fast, and slow), she argues that we’re all wired to pray to a god for help in a dark and stormy night. But when it comes to the next morning, well, our slow, sober judgment generally tells us that what we’ve called on was a fantasy. How silly of me! Luhrmann is interested this, and we are, too. What does this say–in an age of inner-protectionism, of rational fears and anxieties–that in the moments of need, when these fears are brought to bear, alone, maybe realistically or maybe not, that our wiring calls to call? And what should this say about the times beyond the storm? Was it all a gag? Was it all “silly me?” Luhrmann suggests not.

Consider how some people attempt to make what can only be imagined feel real. They do this by trying to create thought-forms, or imagined creatures, called tulpas. Their human creators are trying to imagine so vividly that the tulpas start to seem as if they can speak and act on their own. The term entered Western literature in 1929, through the explorer Alexandra David-Néel’s “Magic and Mystery in Tibet.” She wrote that Tibetan monks created tulpas as a spiritual discipline during intense meditation. The Internet has been a boon for tulpa practice, with dozens of sites with instructions on creating one.

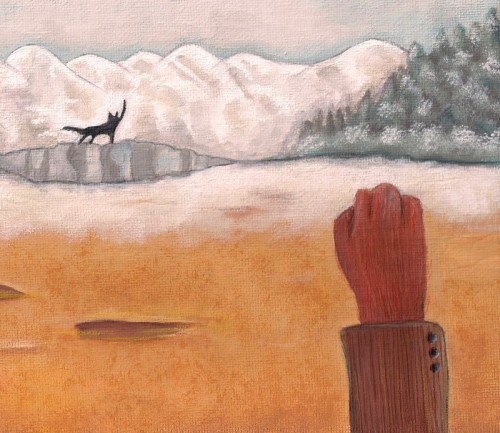

Jack, a young man I interviewed, decided to make a tulpa when he was in college. He set aside an hour and a half each day for this. He’d spend the first 40 minutes or so relaxing and clearing his mind. Then he visualized a fox (he liked foxes). After four weeks, he started to feel the fox’s presence, and to have feelings he thought were the fox’s.

Finally, after a chemistry exam, he felt that she spoke to him. “I heard, clear as day, ‘Well, how did you do?’ ” he recalled. For a while he was intensely involved with her, and said it felt more wonderful than falling in love with a girl. Then he stopped spending all that time meditating — and the fox went away. It turned out she was fragile. He says she comes back, sometimes unexpectedly, when he practices. She calms him down.

The mere fact that people like Jack find it intuitively possible to have invisible companions who talk back to them supports the claim that the idea of an invisible agent is basic to our psyche. But Jack’s story also makes it clear that experiencing an invisible companion as truly present — especially as an adult — takes work: constant concentration, a state that resembles prayer.

It may seem paradoxical, but this very difficulty may be why evangelical churches emphasize a personal, intimate God. While the idea of God may be intuitively plausible — just as there are no atheists in foxholes, there are atheists who have prayed for parking spots — belief can be brittle. Indeed, churches that rely on a relatively impersonal God (like mainstream Protestant denominations) have seen their congregations dwindle over the last 50 years.

To experience God as walking by your side, in conversation with you, is hard. Evangelical pastors often preach as if they are teaching people how to keep God constantly in mind, because it is so easy not to pray, to let God’s presence slip away. But when it works, people experience God as alive. Secular liberals sometimes take evolutionary psychology to mean that believing in God is the lazy option. But many churchgoers will tell you that keeping God real is what’s hard.

Now, on one hand, the discussion of belief as a psychological “practice,” of disciplined structure to “place God” in your day, this seems not to corroborate the idea of faith being “given” by God. And surely, the moments of faith’s presence, in the face of dire need, seem to me to be the most potent states of belief, the ones that end up creating the initiative for a fox-companion tulpa. But what I find interesting is–now matter how “brittle” belief may be–the enmeshed sense of human beings to have invisible companionship.

Now, on one hand, the discussion of belief as a psychological “practice,” of disciplined structure to “place God” in your day, this seems not to corroborate the idea of faith being “given” by God. And surely, the moments of faith’s presence, in the face of dire need, seem to me to be the most potent states of belief, the ones that end up creating the initiative for a fox-companion tulpa. But what I find interesting is–now matter how “brittle” belief may be–the enmeshed sense of human beings to have invisible companionship.

Changing gears, kind of, Luhrmann’s short piece, “The Violence in Our Heads,” was released last month in reaction to the Navy Yard shootings, and the subsequent firestorm of political rabble that came from it about “the schizophrenia issue.” Luhrmann points out that schizophrenia is not necessarily connected with violent voices in our head–a study showed that schizophrenics in India are less likely to have violent voices manipulating them–but that our American aversion to facing and speaking back to these voices are only aggravating the problem. Can you see the connection between these articles? Sounds like Christian prayer to me–calling upon that “invisible companion” to face one’s reality, to move into (and through) the storm of voices…

The Hearing Voices movement encourages people who hear distressing voices to identify them, to learn about them, and then to negotiate with them. It is an approach that flies in the face of much clinical practice in the United States, where psychiatrists tend to assume that treating such voices as meaningful encourages those who hear them to give them more authority and to follow their commands.

Yet while there is no judgment from the scientific jury at this point, there is evidence that at least some people find that when they use the Hearing Voices approach, their voices diminish, become kinder and sometimes disappear altogether — independent of any use of drugs.

This evidence is strengthened by a recent study in London that taught people with schizophrenia to create a computer-animated avatar for their voices and to converse with it. Patients chose a face for a digitally produced voice similar to the one they were hearing. They then practiced speaking to the avatar — they were encouraged to challenge it — and their therapist responded, using the avatar’s voice, in such a way that the avatar’s voice shifted from persecuting to supporting them.

All of the 16 patients who received a six-week trial of that therapy found that their hallucinations became less frequent, less intense and less disturbing. Most remarkably, three patients stopped hearing hallucinated voices altogether, even three months after the trial. One of those three patients had heard voices incessantly for the prior 16 years.

The more we know about the auditory hallucinations of schizophrenia, the more complex voice-hearing seems and the more heterogeneous the voice-hearing population becomes. Not everyone will benefit from the new approaches. Still, they offer hope for those struggling with a grim disease. Meanwhile, it is a sobering thought that the greater violence in the voices of Americans with schizophrenia may have something to do with those of us without schizophrenia. I suspect that the root of the differences may be related to the greater sense of assault that people who hear voices feel in a social world where minds are so private and (for the most part) spirits do not speak.

We Americans live in a society in which, when people feel threatened, they think about guns. The same cultural patterns that make it difficult to get gun violence under control may also be responsible for making these terrible auditory commands that much harsher.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XWXynfTR9SY&w=600]

COMMENTS

3 responses to “T.M. Luhrmann’s Theory on Voices and Tulpa-Gods in Your Head”

Leave a Reply

Great article, and love the artwork. I’ve been seeing these coming up all over the place since that new york times article. Tulpas are a neat discussion, and I recall an article where researchers found people who communicate with God and take x minutes per day to talk and talk with him, sounds similar to the techniques on tulpa.info to create a tulpa.

I think this particular work of psychology is a lot less sympathetic to the Christian viewpoint than you make it sound. Sure, Luhrmann’s tone may be sympathetic and compassionate and her work may demonstrate how people have a sense of an invisible companion. BUT it also implies (directly or not) that either God is nothing but a tulpa, or (if God does exist) that we never actually communicate with anything more than the imaginary version of God that we create in our head. To be honest, I have a similar critique for most Mbird articles that center around psychology; as a discipline, it is much less religion-friendly (or people-friendly, for than matter) than one might think.

Matt, I’m curious to know how you think psychology is less religion-friendly (or people friendly) than one might think. I agree that psychology is NOT religion-friendly, if by ‘religion-friendly’ we mean ‘in support of the existence of God or some ultimate spiritual reality as proposed by religions’. I think psychology at best is agnostic on that; and at worst, like most academic disciplines that assume the scientific method or reductionism, can be used against religion. I suppose it depends on your view of whether any empirical research methodology is religion-unfriendly. To me, the best psychology is that which remains agnostic about truth claims concerning ultimate realities, but is able to accurately describe people’s experiences and can provide insight about what *we* are like, as embodied creatures who have these experiences.