It may be perceived that my sympathies, which lately seemed to lie so rightly on the side of the poor overmatched hitters, have unaccountably swung the other way. I admit this indefensible lapse simply because I find the spitter so enjoyable for its deviousness and skulking disrespect… Baseball is a hard, rules-dominated games, and it should have more room in it for a little cheerful cheating. –Roger Angell

Tonight begins the 109th recorded issue of America’s Fall Classic, showcasing the likely AL and NL pennant winners: the Red Sox and the Cardinals. They come to it by various rites–2012’s cellar-dwelling BoSox put down 93 losses, for the first time in nearly 50 years, and then installed a new manager and new sluggers this season, and here they are; the slow-cooking Fredbirds had their World Series win just two seasons back, and didn’t have too much to complain about last season, either–but both teams have been notably hot this season, and carry their number one seed all the way to the Big One. The Cardinals fizzed out the drama of a much-begabbed LA Dodgers, with their new skipper Donny Baseball, and the hugely-budgeted comeback of a famous team caught under the wheels. The Cards hushed that storyline, as they were expected to. The BoSox seemed to have been in control since April.

Tonight begins the 109th recorded issue of America’s Fall Classic, showcasing the likely AL and NL pennant winners: the Red Sox and the Cardinals. They come to it by various rites–2012’s cellar-dwelling BoSox put down 93 losses, for the first time in nearly 50 years, and then installed a new manager and new sluggers this season, and here they are; the slow-cooking Fredbirds had their World Series win just two seasons back, and didn’t have too much to complain about last season, either–but both teams have been notably hot this season, and carry their number one seed all the way to the Big One. The Cardinals fizzed out the drama of a much-begabbed LA Dodgers, with their new skipper Donny Baseball, and the hugely-budgeted comeback of a famous team caught under the wheels. The Cards hushed that storyline, as they were expected to. The BoSox seemed to have been in control since April.

So, in some cases, for the first time in 34 years, this year’s Series is a standard. Two numero unos. Unless you are beholden to one of these clubs, this year’s bout is like any historically well-groomed championship. It is the Celtics-Lakers, Kentucky-Kansas, Michigan-Ohio State–maybe there’s bad blood, maybe there’s not, but we’ve been here before (2007), and these teams have earned their place here, again. The match-up is likely, even historically so, and so perhaps, whether you know what baseball is all about, or you don’t, this an opportunity to start watching. Or perhaps it isn’t. There may be lots of beards, but there’s no Cinderella in this one.

I think it is the perfect time to start watching baseball. I think baseball is what the American needs right now–and I mean this quite seriously–precisely and fundamentally because no American knows what it means to pay attention anymore, and no one likes slow. Baseball provides both without their necessity for enjoyment. Watching baseball is conversational fare, and then it interrupts you, when it needs to, with a thhhhwack! down the line. You don’t have to pay attention–it will remind you when you’re missing something–but the life it lends you when you do, like poetry or a walk, enchants. It lends the kind of seat of awareness that props a human being up against the current undertow of public attention, and says Listen, “Here we are. Two on, one out, runners at first and third, count is two balls, one strike, bottom of the third. Wainwright from the stretch and he’s nicking corners, but he’s got himself in a bind here.”

I think it is the perfect time to start watching baseball. I think baseball is what the American needs right now–and I mean this quite seriously–precisely and fundamentally because no American knows what it means to pay attention anymore, and no one likes slow. Baseball provides both without their necessity for enjoyment. Watching baseball is conversational fare, and then it interrupts you, when it needs to, with a thhhhwack! down the line. You don’t have to pay attention–it will remind you when you’re missing something–but the life it lends you when you do, like poetry or a walk, enchants. It lends the kind of seat of awareness that props a human being up against the current undertow of public attention, and says Listen, “Here we are. Two on, one out, runners at first and third, count is two balls, one strike, bottom of the third. Wainwright from the stretch and he’s nicking corners, but he’s got himself in a bind here.”

The pace of the game, of course, is contrary to most. The NFL, much to its chagrin, motivates the kind of concussion-loving fanmanship it is currently working against, because the sport loves speed. It’s not just the shorter play clock, the shotgun, the spread offense, the idolatry of the wide receiver–it’s also the televised cult of the sport. It’s Carrie Underwood on Sunday Night Football–lasers cresting over Clay Matthews, robot lights lining up Eli’s arm, the smartphone embedded in the whole space-age tackle party. The NBA is certainly no different–how many times have you seen an NBA player on a smart phone in an ad, even during the offseason? Sure, there will be plenty of graphics in tonight’s Pre-Series roundup, and the television seems to become more and more littered with “K-Zones” and “Stat-Trackers,” but Major League Baseball has somehow missed the limelight of major commercial advertisements–and I think speed has something to do with it, particularly speed to score.

Lovers of the non-American variety of “slower” ball–tennis, soccer, golf–will raise up in defense, but here it gets to something different, more elemental. While each of these may lack the hurried and prodigious numbers of big scores, all of them sustain a perpetual movement of some sort. A golfer is always moving, swinging, wiggling in relation to and from the hole, and then the next, and then the next. In soccer, big scores are abrupt moments in a gradual crescendo of perpetual movement. Tennis, perpetual movement, and some would say it is not slow at all. On a baseball field, though, you find a flat cone largely populated by guys standing around, ready for something to happen. With baseball, no one is moving at all except for the pitcher and the batter, for sometimes vast stretches of time. And yet, for all the stillness–and some might call it dreadful boredom–there is a supreme cognitive awareness, pitch by pitch, in every position on the field, of the circumstances of things. Each player, like a real human being, appears to be standing around, but, in reality, is fixing in like a wound band of the mind, ready to spring upon any of the external potentials. He crouches, the pitch is released. Low and outside, the batter doesn’t bite. Ball. He unwinds the spool, and rewinds it for the new circumstances at hand.

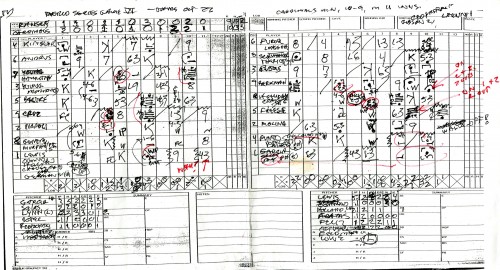

This present energy is everywhere on the field. Baseball fans in the park map it out, too; they have diagrams in books and mark it out pitch by pitch, sometimes every game for every season. Say there are runners at the corners, a deft hitter at the plate, with one out. One ball, two strikes. It’s the fifth inning and it’s close. The guy in right field–you’re not paying attention to him because he’s not on the screen–he’s “playing back,” ready and still in the deeper reaches of his territory, ready to come in on a hit-and-run, which is possible because this particular (right-handed) hitter is experienced with going the opposite way with an outside pitch. The second baseman, on the other hand, is playing tight to the bag. He and the catcher know the runner on first is running, but they also know that if the slider falls just right, they easily have the chance for a strike-em-out-throw-em-out double play. Either way, it’s a tough call, though, because if the batter punches the slider right, what could have been a routine, inning-ending double play becomes an easy base knock, and you’re looking at one run in, and no outs added. The second baseman falls back to his position, and shortstop nears the bag to cover. Now the hole is on the left side of the field, and the batter will try to pull it.

All goes still. The pitch comes, that slider, and it paints the corner, but not enough. Ball two. Reset.

It is liturgical, watching the ball come back to the pitcher, who slides his glove off, milks the ball in the fat of his hands, ponderously lopes to the back of the mound, re-gloves, saddles back into the stretch, sets, and throws again. This, too, is strange. Unlike any sport, defense is offense and offense is defense. The Chief Defender, the pitcher, is the man hurling a 90-mph heater within inches of the batter’s elbow, and the batter, the Offense, must defend his chest-high, knee-low rectangle of air from the nine men around him. In any other sport but life is this true? That the moment of proving is actually making your defensiveness look like offense? A batter swings–still with the lingering distrust that a pitcher’s competitiveness might fall victim to his malice–and perhaps, perhaps, the bat keeps its province safe.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EpMlVptg2Ls&w=600]

There is a fantastic order to baseball, given the scope of the field and the size of the ball. Roger Angell says,

I don’t think anyone can watch many baseball games without becoming aware of the fact that the ball, for all its immense energy and unpredictability, very rarely escapes the control of the players. It is released again and again–pitched and caught, struck along the ground or sent high in the air–but almost always, almost instantly, it is recaptured and returned to control and safety and harmlessness. Nothing is altered, nothing has been allowed to happen. This orderliness and constraint are among the prime attractions of the sport; a handful of men, we discover, can police a great green country…

This mindful order establishes the clockwork of baseball, a perception of neat-freak control. A groundball seems lucky to find a hole in the defense, a flyball nearly always finds its home in a glove. If you cannot read a scoreboard or hear a commentator, still, the pitches come like the ocean with undulating ease. Yes, you’re right, it seems boring. To have no intrusion, no entrance of chaos–or freedom–into the repetitive structure of a game, there’s no enjoyment, no life there.

“Almost always, almost instantly.” Baseball would be meaningless without order, but baseball would also be dreadful with only order. Can you relate? There is beauty in the notions of order and professionalism–we root for such clean control. But in baseball, a controlled game is a scoreless game, and an error-filled game is as hard to watch as a scoreless one. Order is not the end, but the beginning, drawn out by the intrusive crack of the bat, which inevitably comes in the wake of the routine. With a base hit, or a knuckler, or a pretzel-bending slider, a trick has been thrown into the order, after spaces of quiet routine. In the midst of such an orderly game, with all the time to assess one’s present situation, the runs are scored in the chaotic release of them. After minutes, hours of ball-control, the ball is set free, and the fielders scramble to fix it. Unlike any other sport, offensive scoring is making the defense deal with a ball going rogue.

“Almost always, almost instantly.” Baseball would be meaningless without order, but baseball would also be dreadful with only order. Can you relate? There is beauty in the notions of order and professionalism–we root for such clean control. But in baseball, a controlled game is a scoreless game, and an error-filled game is as hard to watch as a scoreless one. Order is not the end, but the beginning, drawn out by the intrusive crack of the bat, which inevitably comes in the wake of the routine. With a base hit, or a knuckler, or a pretzel-bending slider, a trick has been thrown into the order, after spaces of quiet routine. In the midst of such an orderly game, with all the time to assess one’s present situation, the runs are scored in the chaotic release of them. After minutes, hours of ball-control, the ball is set free, and the fielders scramble to fix it. Unlike any other sport, offensive scoring is making the defense deal with a ball going rogue.

Maybe you caught it. Chances are, if you were zoomed in on the K-Zone, or the whatever-you-call-it, you didn’t catch it, that flitter of a new something in the pitcher’s planned errand. But it doesn’t matter–you will hear it. It will break loose in a bat flash and all control will be gone, and we’ll all get up and cheer on the fracas.

[youtube=www.youtube.com/watch?v=U157X0jy5iw&w=600]

COMMENTS

5 responses to “On Spitters and Change-Ups and the American Need for Baseball”

Leave a Reply

Thanks for a great piece of writing that really gets at what the great game of baseball is all about. And don’t forget defeat. Baseball is also about defeat, and the humility it brings, or at least can and should bring, to the defeated, who are all those who have ever played the game. When even the best batters fail almost 7 out of 10 times at the plate, and the best pitchers are worn out after 7 innings, if not before, and even the best fielders can always make a crucial error that costs a game, that is a game that every Christian ought to love.

Beautiful essay, Ethan.

You might be interested in two short pieces I came across in the ’90’s [yes, I’m that old].

One is “The Mickey Mantle Koan: The Obstinate Grip of An Autographed Baseball” by David James Duncan. It originally appeared in Harpers magazine September 1992 issue.

There are copies of the piece here:

mrhaynes.net/text/HarpersMagazine-1992-09-0001008.pdf

and here: http://www.brunswick.k12.me.us/hdwyer/a-mickey-mantle-koan-by-david-james-duncan/

The other is from the Buddhist magazine Tricycle, the Summer 1993 issue. It’s called “The Baseball Diamond Sutra.” This one is quirky, but lots of fun.

http://www.tricycle.com/editors-view/the-baseball-diamond-sutra

Check them out; you might enjoy them.

PITCHER by Robert Francis

His art is eccentricity, his aim

How not to hit the mark he seems to aim at,

His passion how to avoid the obvious,

His technique how to vary the avoidance.

The others throw to be comprehended. He

Throws to be a moment misunderstood.

Yet not too much. Not errant, arrant, wild,

But every seeming aberration willed.

Not to, yet still, still to communicate

Making the batter understand too late.

Baseball has typically inspired the best writing of any sport, and you contribute to that remaining the case with this excellent piece. You magnify the point by quoting the great Roger Angell.

that. is. brilliant.

thank you.