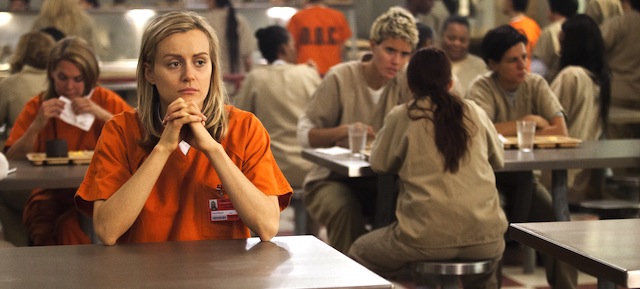

In prison, nothing comes for free—not food, not shower shoes, not even the past. For Piper Chapman, who goes from West Village yuppie to inmate, learning this comes at a tremendous price. Orange is the New Black is Netflix’s latest TV project and was released all at once in mid July for our binge-watching enjoyment. The show is (loosely) based on Piper Kerman’s memoir of the same title and follows protagonist Piper Chapman, a blonde with a Seven Sisters education, after she receives a 15-month sentence for having been involved with her ex-girlfriend’s international drug ring about 10 years prior. The verdict comes as a surprise to Piper, who is now living an upstanding life, as she is forced to revisit and account for a past that she thought she’d permanently left behind.

By the end of the first episode, I was hopelessly committed to this show—although, it might have captured my loyalty as early as the opening credits (that Regina Spektor song is so good), which flash close-ups of incarcerated women’s faces—eyes, mouths, some with freckles, some with piercings. As early on as this credit sequence, you, the viewer, are already wondering, “What did these women do? How did they get here? What are their stories?” The show plays off of this desire for explanation and story so well—as you meet each new character, you can’t help but wonder what they did, what happened in their lives, to land them in jail. And, episode by episode, you are taken back to the crimes of each character through a series of flashbacks—when they stole out of necessity, when they covered for a loved one and took the fall, or when they just made a mistake.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fBITGyJynfA&w=600]

Orange messes with your judgments, with the personal verdicts you decide for each character. Every time you conclude that someone is heartless or corrupt, that judgment is called into question as you learn more about their life, or see their vulnerabilities laid bare. The show plays your empathy perfectly—each character is some measure of despicable and admirable, pitiable and unsympathetic, and the balance is artfully kept. Just when you think someone is reprovable, you are given a glimpse into their psychology—the needs and fears that act as motivators. The whole idea of criminality is undermined as the shifting mosaic of lives reveals that each character is part guilty and part innocent. Todd VanDerWerff of the A.V. Club applauds this facet of the show. (To avoid spoilers, stop reading now.)

In fact, I loved how the show had the courage to make almost everyone in the cast believably selfish and petty and loathsome at one point or another. The characters you expect to hate all of the time—like the usually loathsome Pornstache—have moments when they do good things, and it’s not solely because of their own self-interest, nor is it something that really shifts your overall opinion on them…Every single character does at least one good thing and at least one bad thing in the course of the season, and they all occupy a complex, sliding scale of morality.

…Unlike the gleeful antiheroes who increasingly make up the realm of “quality drama,” the characters on Orange hold grudges and understand their own power to hurt and build up their fellow inmates. The more the show goes on, the more we understand their

points-of-view, and the more we understand how an offhand remark can end up feeling more cruel than its intention, or how terrifying a feud between the characters can be. And at all times, the characters are completely understandable when they’re doing awful things… And in the end, there may be no more troubled, complicated character than the protagonist, who keeps playing her fiancée and her ex-girlfriend off each other, until she has neither and ends up isolated in that snowy yard in the final scene by her own hand.

Every character, from the transgender hairdresser to the hillbilly Bible thumper, is pushed to their limits in a prison that acts as an incubator for grudges, psychoses, and fears. Without familiar comforts, respect, or sometimes, basic rights, many characters fall back into criminal patterns of behavior. Tastee is readmitted just weeks after she gets out, and Tricia overdoses right after she’s sweated herself clean. The harsh circumstances of prison seem almost designed to bring out the worst in everyone. And so, while the events often seem outside of the characters’ control, there is also the idea that serving time—fulfilling the demands of the law—does not lead to personal rehabilitation or improvement.

The worst part of prison, the part that corrodes each character’s resolve and hope between the cinder-block walls and under the fluorescent lights, is the space for introspection. It’s a grossly magnified time-out: you have years to sit in the corner and think about what you’ve done. As VanDerWerff says,

Prison isn’t the blogging project the protagonist almost seems to mistake it for early in the first episode or a place where her past won’t matter. For as much as everyone in the prison says what happened to put them there doesn’t matter, it clearly does. Prison isn’t a place to atone for your history or even forget about it; it’s a place where that history comes fully to bear and forces you to come to terms with who you really are.

The most compelling scene that illustrates this comes in the 10th episode, “Bora Bora Bora,” where some delinquent teens visit the prison so that the inmates can scare them into behaving and upholding the law (because that always turns out well). One particularly recalcitrant juvenile, Dina, needs some extra scaring, and the other inmates decide to let Piper do the job. Piper succeeds by brutal honesty. Here’s the (edited) conversation:

Dina: So, uh, now’s the part where you try to scare me?

Piper: No. No, I really—I don’t want to scare you. But, um, believe me you don’t wanna be in here…You know I could tell you a lot of things that would scare you, Dina. I could tell you that I’m gonna make you my prison b**ch. I could tell you that I’m gonna make you my house mouse. That I will have sex with you even if we don’t have an emotional connection. That I’m gonna do to you what the spring does with cherry trees but in a prison way. Pablo Neruda. But why bother? You’re too tough, right? Yeah I know how easy it is to convince yourself you’re something that you’re not. And you can do that on the outside, just keep moving, keep yourself so busy you don’t have to face who you really are. But, you’re weak.

Dina: Back the [heck] off me.

Piper: I’m like you, Dina. I’m weak too. I can’t get through this without somebody to touch. Without somebody to love. Is that because sex numbs the pain? Or is it because I’m some evil [sex]

monster? I don’t know. But I do know I was somebody before I came in here. I was somebody with a life that I chose for myself. And now—now it’s just about getting through the day without crying. And I’m scared. I’m still scared. I’m scared that I’m not myself in here, and I’m scared that I am. Other people aren’t the scariest part of prison, Dina, it’s coming face to face with who you really are. Because once you’re behind these walls, there’s nowhere to run, even if you could run. The truth catches up with you in here, Dina. And it’s the truth that’s gonna make you a b**ch.

There were definitely a few moments in the season that irritated me. The psycho, hyper-hypocritical fundamentalist Pennsatucky is the voice of “Christianity” in the show and, although there’s one moving scene where she forces Piper to pray and the prayer comes out semi-sincere, Pennsatucky’s character repeatedly made me roll my eyes and think, “Really?? Like we haven’t seen enough ignorant, toothless bigots representing Christianity on TV.” The last scene also bothered me initially. When Piper flies off the handle and beats Pennsatucky (to death? To within an inch of her life? We’ll have to wait and see), I worried that here the Nancy Botwin archetype was starting to appear—someone who gets involved in something disreputable because they feel they have to and winds up a hardened, unreadable criminal once they start getting their hands dirty (Jenji Kohan also directed Weeds). But, the more I’ve thought about it the more I’ve come to see that Piper’s evolution, to the point of this violence, makes sense. Her trajectory has brought her face to face with the ugliest parts of herself and repelled her loved ones. She’s only now becoming aware of how screwed up—and how similar to all the other inmates—she is. And while the exploration of our fallen, self-serving state probably won’t happen under the overt religion of the show, I’m sure these themes of remorse, rehabilitation and repentance will continue to evolve in the next season, pushing us outside of our comfort zones and enthralling us at the same time.

COMMENTS

2 responses to “And The Law Won (Or Did It?): Netflix’s Orange is the New Black”

Leave a Reply

Good call- I didn’t really think about her. She was a pretty neutral character for me, probably largely because she plays a minor role. She’s not exceptionally saintly (she refuses to give Sofia her hormone pills) but she seems to give pretty sound advice (again to Sofia, regarding her wife), so she seems balanced. Maybe she serves as a sort of foil for the other religious character, Pennsatucky, by being coolheaded and rational. Just some quick thoughts- I’d love to hear other takes, though.