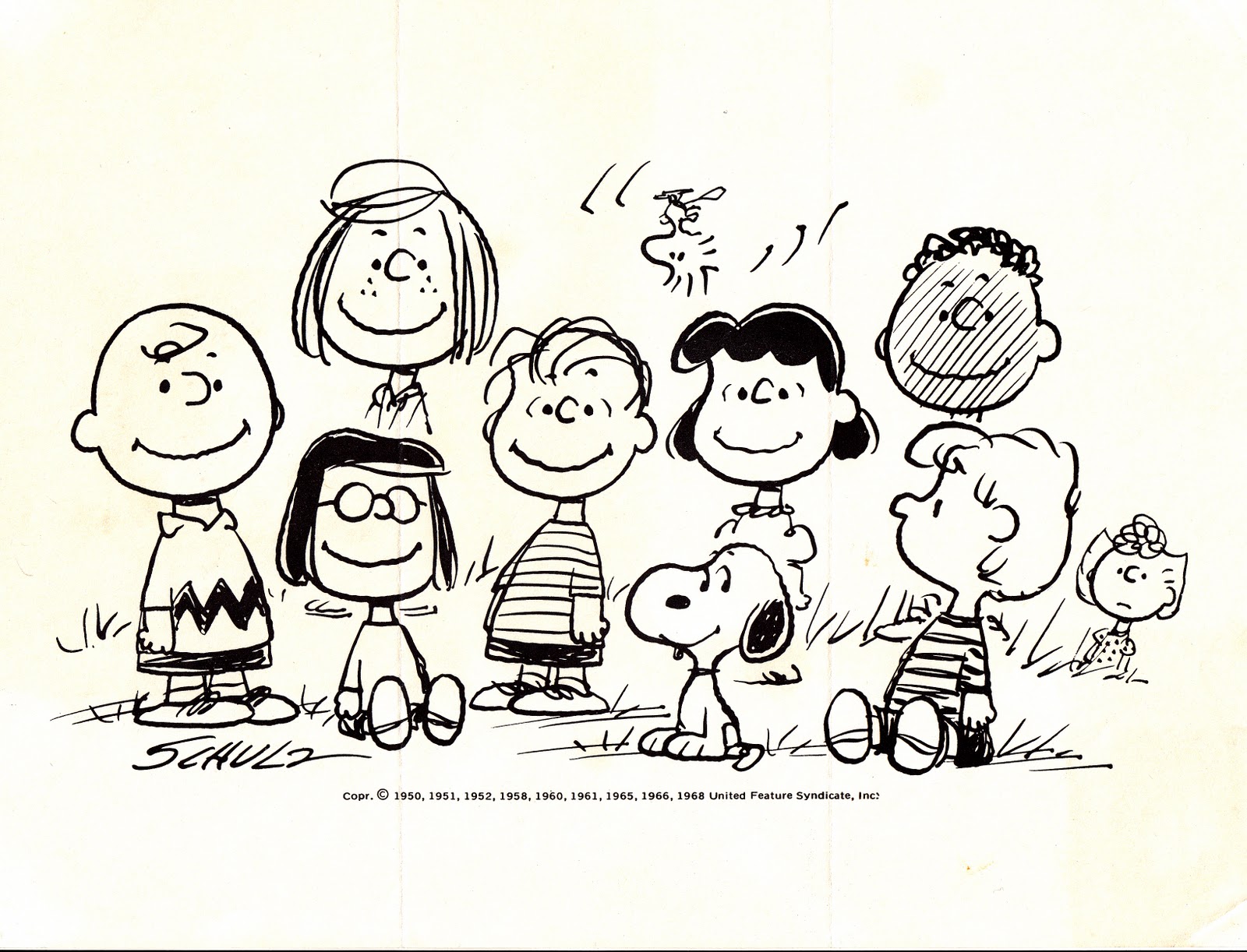

We have written several pieces on Charles Schulz’s Peanuts here before, and in particular on Robert L. Short’s prophetic interpretation in his The Gospel According to Peanuts (1965) here, here, and here. Both Peanuts in general and Short’s book in particular have played meaningful roles in my life ever since my conversion to Christian faith. In fact, I recently reread Short’s very important (and Mockingbird-esque) first chapter, “The Church and the Arts.” I found that he gives us—as Thornton Wilder called it—some “new persuasive words for defaced or degraded ones” about Pentecost and the Holy Spirit’s work in the arts and the Church today.

In the spirit of Pentecost coming once again this Sunday, here are some highlights from that first chapter, in which Short explains his own project of interpreting the art of Peanuts:

Far too often the Church finds itself in the trap of attempting to explain its position in a language that is itself not meaningful. When Linus asks his mother why he cannot ‘slug’ Lucy, who has taken his book of stories, his mother answers, ‘That’s just one of those things I can’t explain.’ But Lucy has an explanation: ‘Listen, dope!’ she tells Linus, with her fist in his face, ‘If you slug me, I’ll slug you right back!!’ ‘Never mind, Mom,’ says Linus after silently watching Lucy turn and walk away with his book; ‘It’s just been explained to me in a language I can understand.’ The Church’s missionaries to its ‘cultured despisers’ need to be as well acquainted with the current languages of culture as the Church’s missionaries to foreign lands are acquainted with the languages of the areas into which they are sent. (p. 7) …

Art, just because of its subtlety and indirectness, has a way of sneaking around ‘mental blocks’ and getting to the heart of the matter where it is capable of deeply and literally ‘moving’—even the most immovable—men and women. (p. 8) …

Therefore if there is some truth in art (and it must follow, as the night the day, that the greater the art the more truthful it will be) that the Christian observer can point to, he can then by this means speak a word to his brother who might not be willing to listen in any other way. The artist, then, is like the man who is ‘speaking in strange tongues,’ to use Paul’s language. The ability to speak in tongues Paul saw as one of the great ‘gifts of the Spirit’ within the Church. For to one was given one gift, ‘to another various kinds of tongues, to another the interpretation of tongues’ (1 Cor. 12:10), and so on. But as Paul also pointed out, no one will be able to understand these tongues ‘if there is no one to interpret’ (1 Cor. 14:28). Thus, the Church, rather than always being annoyed by the arts, should encourage a vanguard of men and women to be interpreters of these tongues, or arts, which can act as truly provocative ‘conversation pieces’ between the Church and the culture in which the Church finds itself. (pp. 11-12)

This is a pretty good description of the Mockingbird project, too. As our mission statement reads: “Mockingbird is a ministry that seeks to connect the Christian faith with the realities of everyday life in fresh and down-to-earth ways”. Forgive me for being boastful, but I can’t help noticing important parallels between what Short did nearly 50 years ago, what we at Mockingbird are trying to do today, and how the Holy Spirit was at work at Pentecost back then.

I am growing more and more convinced that not only organizations such as this one but the Church more generally, as Short argues, urgently needs to be interpreting these “strange tongues” for the sake of hardened hearts, blocked intellects, and heavy laden souls and the Good News we might proclaim to them–starting with our own. Such a vanguard of interpreters would surely be something of a new Pentecost, if one could conscionably say such a thing. Or perhaps with Thornton Wilder, we could just call it a rhetorical revival: “The revival in religion will be a rhetorical problem—new persuasive words for defaced or degraded ones.” Surely Short would agree!

Bonus material: Jean Schulz, Charles Schulz’s widow, recently wrote this fascinating blog post about the nature of an important artistic shift detected in his Peanuts corpus, ht DZ. She cites Stephan Pastis, creator of Pearls before Swine, who first noticed that this shift takes place with one particular comic strip in 1954:

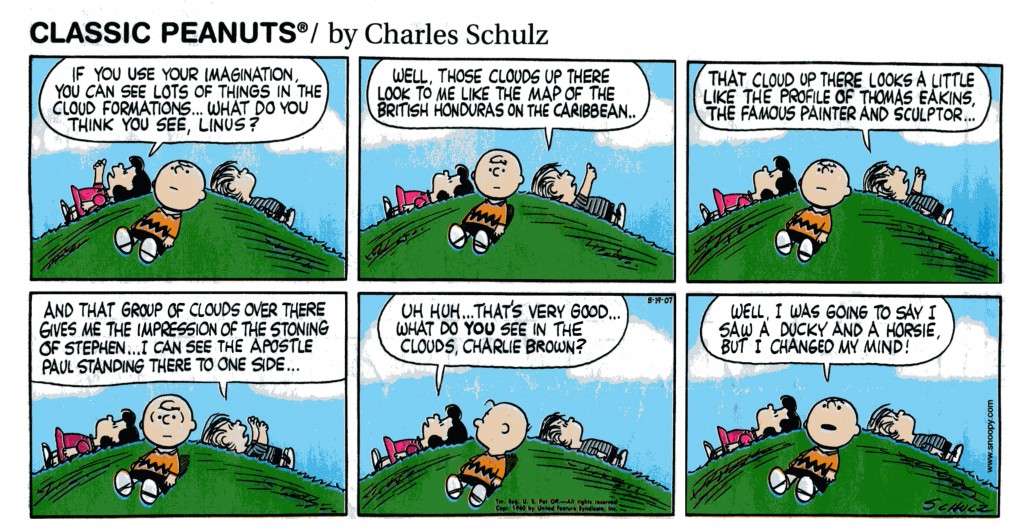

So for the first time in Peanuts, you see real pathos, something which would give the strip its depth. In terms of tone, it is also groundbreaking. In an era when every strip had to be either an adventure strip or a slapstick humor strip, here is a humor strip that is not funny. Boldly not funny. It’s just sad. And moreover, it’s a child being sad. That’s a real departure for both Peanuts and probably most other strips on the comics page.

How then might we interpret the strange tongue of this comic strip? I venture to say that what we find in Charlie Brown is a void or lack of fulfillment that no train set, not even the big fancy one like his friend’s, could ever fill. Like us, when he finally gets the toy he wants, he will be dissatisfied soon again (Matthew 6:19-21). That empty place in our souls can only be filled with the saving grace of God found in Jesus Christ. On that note, and in the spirit of Pentecost, praise Him for this love, and for Schulz and other great artists, for their strange tongues, and for the gift of those like Short who interpret these artistic tongues for us so we might better understand “the mighty works of God.” (Acts 2:11)

[youtube=http://youtu.be/H2H0TfvNU3w&w=600]

COMMENTS

2 responses to “A New Pentecost, or Maybe Just a Rhetorical Revival, According to Peanuts”

Leave a Reply

Matt-

Not sure if you’ve had the chance to read My Bright Abyss yet, but the chapter on “Varieties of Quiet” is essentially a full length meditation on what you (and Short) are talking about – Wiman highlights the need for a “new poetics of belief”, one that reexamines our religious vocabulary without naively (or arrogantly) disregarding the meaning and history in which some of these words are saturated. To reimagine if not reinvent our language for talking about things that can’t ever be fully put into words. Really powerful stuff, esp from a poet.

DZ, I’ll have to do some Wiman homework … still need to catch up on Karr, too. All these new poets you’re introducing to me. I like the sound of “new poetics of belief” … new Pentecost … new persuasive words … Good News, Charlie Brown.