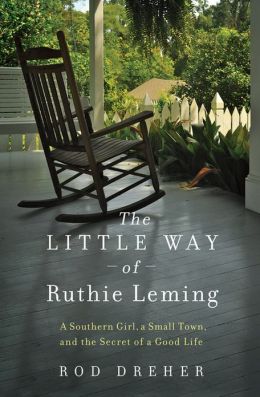

Over at the The Atlantic, Emily Esfahani Smith released a book review-slash-sociological study last week on the relationship between ambition and community. She sets up her article on the recently released memoir of Rod Dreher, whom we’ve mentioned on here before, entitled The Little Way of Ruthie Leming: A Southern Girl, A Small Town, and the Secret of the Good Life. Ruthie Leming is Rod’s sister, the sister who stayed home in small-town Louisiana, who embedded herself in her childhood community, who embraced the ordinariness of her present and who, in her time of great and unexpected weakness (cancer), found a community to lovingly take care of her. Rod, on the other hand, was on the fast-track out of Louisiana. Ambitious and jet-set, his story draws a line of distance between him and his sister, and the distinction between the myth of self-definition and the defining that comes from being still, where you are. Dreher describes this distinction as an “invisible wall” that developed between his sister and him: ambition built an incommunicable barrier that was only made visible when Ruthie was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer in 2010. This defining, life-ending destiny for Ruthie becomes a powerful contrario to Rod’s m.o. He sees more life in the community of a dying woman than he does in himself.

Over at the The Atlantic, Emily Esfahani Smith released a book review-slash-sociological study last week on the relationship between ambition and community. She sets up her article on the recently released memoir of Rod Dreher, whom we’ve mentioned on here before, entitled The Little Way of Ruthie Leming: A Southern Girl, A Small Town, and the Secret of the Good Life. Ruthie Leming is Rod’s sister, the sister who stayed home in small-town Louisiana, who embedded herself in her childhood community, who embraced the ordinariness of her present and who, in her time of great and unexpected weakness (cancer), found a community to lovingly take care of her. Rod, on the other hand, was on the fast-track out of Louisiana. Ambitious and jet-set, his story draws a line of distance between him and his sister, and the distinction between the myth of self-definition and the defining that comes from being still, where you are. Dreher describes this distinction as an “invisible wall” that developed between his sister and him: ambition built an incommunicable barrier that was only made visible when Ruthie was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer in 2010. This defining, life-ending destiny for Ruthie becomes a powerful contrario to Rod’s m.o. He sees more life in the community of a dying woman than he does in himself.

Smith takes this story in order to delve deeper into the ambition-community divide. She talks about the intrinsic nature of ambition to objectify relationships, how ambition–the desire to top ladders or acquire more–provides an insulated struggle. Like Francis Underwood, or Don Draper, or Walter White, the entire world begins to look like either a supporting role or complicating role in one’s quest for self-realization. Ambition, paradoxically, creates a different kind of “unvisited tombs,” she says, a society in which no one belongs unconditionally. The question becomes, what happens when I get what I want? And if I get everything I’ve longed for, is it freedom? Smith also talks about religious communities, and how the notions of permanent communal belonging give people a greater sense of “the good life” than ambition provides. It provides a graciously limiting Other. While I wouldn’t say it is just the community of other believers and achievers you share pews with, it certainly is the message of unconditional “belonging” that tends to turn the “good life” paradox upside-down. It’s worth reading in full, but here are some great excerpts:

The conflict between career ambition and relationships lies at the heart of many of our current cultural debates, including the ones sparked by high-powered women like Sheryl Sandberg and Anne Marie Slaughter. Ambition drives people forward; relationships and community, by imposing limits, hold people back. Which is more important? Just the other week, Slate ran a symposium that addressed this question, asking, “Does an Early Marriage Kill Your Potential To Achieve More in Life?” Ambition is deeply entrenched into the American personae, as Yale’s William Casey King argues in Ambition, A History: From Vice to Virtue — but what are its costs?

In psychology, there is surprisingly little research on ambition, let alone the effect it has on human happiness. But a new study, forthcoming in the Journal of Applied Psychology, sheds some light on the connection between ambition and the good life. Using longitudinal data from the nine-decade-long Terman life-cycle study, which has followed the lives and career outcomes of a group of gifted children since 1922, researchers Timothy A. Judge of Notre Dame and John D. Kammeyer-Mueller of the University of Florida analyzed the characteristics of the most ambitious among them. How did their lives turn out?

The causes of ambition were clear, as were its career consequences. The researchers found that the children who were the most conscientious (organized, disciplined, and goal-seeking), extroverted, and from a strong socioeconomic background were also the most ambitious. The ambitious members of the sample went on to become more educated and at more prestigious institutions than the less ambitious. They also made more money in the long run and secured more high-status jobs.

But when it came to well-being, the findings were mixed… Kammeyer-Mueller said that while the more ambitious appeared to be happier, that their happiness could come at the expense of personal relationships. “Do these ambitious people have worse relationships? Are they ethical and nice to the people around them? What would they do to get ahead? These are the questions the future research needs to answer.”

Existing research by psychologist Tim Kasser can help address this issue. Kasser, the author of The High Price of Materialism, has shown that the pursuit of materialistic values like money, possessions, and social status-the fruits of career successes-leads to lower well-being and more distress in individuals. It is also damaging to relationships: “My colleagues and I have found,” Kasser writes, “that when people believe materialistic values are important, they…have poorer interpersonal relationships [and] contribute less to the community.” Such people are also more likely to objectify others, using them as means to achieve their own goals.

So if the pursuit of career success comes at the expense of social bonds, then an individual’s well-being could suffer. That’s because community is strongly connected to well-being. In a 2004 study, social scientists John Helliwell and Robert Putnam, author of Bowling Alone, examined the well-being of a large sample of people in Canada, the United States, and in 49 nations around the world. They found that social connections — in the form of marriage, family, ties to friends and neighbors, civic engagement, workplace ties, and social trust — “all appear independently and robustly related to happiness and life satisfaction, both directly and through their impact on health.”

This may explain why Latin Americans, who live in a part of the world fraught with political and economic problems, but strong on social ties, are the happiest people in the world, according to Gallup. It may also explain why Dreher’s Louisiana came in as the happiest state in the country in a major study of 1.3 million Americans published in Science in 2009… Meanwhile, wealthy states like New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and California were among the least happy, even though their inhabitants have ambition in spades; year after year, they send the greatest number of students to the Ivy League.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=suRDUFpsHus&w=550]

In another study, Putnam and a colleague found that people who attend religious services regularly are, thanks to the community element, more satisfied with their lives than those who do not. Their well-being was not linked to their religious beliefs or worshiping practices, but to the number of friends they had at church. People with ten or more friends at their religious services were about twice as satisfied with their lives than people who had no friends there.

These outcomes are interesting given that relationships and community pose some challenges to our assumptions about the good life. After all, relationships and community impose constraints on freedom, binding people to something larger than themselves. The assumption in our culture is that limiting freedom is detrimental to well-being. That is true to a point. Barry Schwartz, a psychological researcher based at Swarthmore College, has done extensive research suggesting that too much freedom — or a lack of constraints — is detrimental to human happiness. “Relationships are meant to constrain,” Schwartz told me, “but if you’re always on the lookout for better, such constraints are experienced with bitterness and resentment.”

Dreher has come to see the virtue of constraints. Reflecting on what he went through when Ruthie was sick, he told me that the secret to the good life is “setting limits and being grateful for what you have. That was what Ruthie did, which is why I think she was so happy, even to the end.”

Meanwhile, many of his East Coast friends, who chased after money and good jobs, certainly achieved success, but felt otherwise empty and alone. As Dreher was writing his book, one told him, “Everything I’ve done has been for career advancement … And we have done well. But we are alone in the world.” He added: “Almost everybody we know is like that.”

In the final paragraph of the novel Middlemarch, George Eliot pays another kind of tribute to the dead. Eliot writes, “The growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.”

In other words, those many millions of people who live in the “unvisited tombs” of the world, though they may not be remembered or known by you and me, are the ones who kept the peace of the world when they were alive. For Dreher, Ruthie is one of those people. She was, he told me, “A completely unfussy, ordinary, neighborly person, who you’d never notice in a crowd, but whose deep goodness and sense of order and compassion saved the day.”

Dreher also said of his sister, “What I saw over the course of her 19-month struggle with cancer was the power of a quiet life lived faithfully with love and service to others.” While Ruthie, an ordinary person, did not live the kind of life our culture celebrates, she “penetrated deeply into the lives of the people she touched,” Dreher told me. “She did not live life on the surface.”

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VHblupxLeOI&w=600]

COMMENTS

8 responses to “Ambition’s Invisible Walls and the “Good Life” Ruthie Lived”

Leave a Reply

Great piece Ethan. How about this from Christian Wiman: …all ambition has the reek of disease about it, the relentless smell of the self – the need for approval…to make ourselves more real to ourselves ~ My Bright Abyss

Ethan, thanks for this. I’ve been fan of Dreher’s for over a decade and I am anxious to read the book. Much has been said of the Christian virtues of the book, but I wonder how much of it will end up being well-intended, well-meaning law. Dreher is a former Catholic turned Orthodox and it is apparent that his view of the Christian faith would, in many respects, clash with our Protestant understanding of imputed grace.

Van Morrison nailed it in four verses with “I’m Tired Joey Boy”.

This one got me good; hits close to home. I’m reading it to my small group tonight. Thanks, Ethan.

Great post Ethan! I’m currently reading Allain de Botton’s Status Anxiety, and it hits some similar notes; what a great book! A genial reasonable atheist that will give religion its wins is far more “dangerous” than the militant atheists, don’t you think?

I was struck very hard by the message of this post simply coming home to my tiny town of Everson WA after being in NYC. I loved NY but I was really glad to be at home in my beautiful little town. However, is all “ambition” evil, or is there a place in the walk of grace for it? Paul the Apostle certainly had ambitions, yet he admonished people to stay at home and work quietly with their hands. So, there is grace for everything because nothing is ever enough, and our only peace is not staying small-town or going jet-set, but Christ alone.