1) Club Penguin is one of several multimedia and game sites geared towards tweens from the ages of seven to twelve. Club Penguin itself has over 200 million registered users worldwide, and was purchased by Disney not long ago. And there are plenty of others: Poptropica, Wee World, Moshi Monsters, Fantage. Alongside the sheer breadth of these programs’ appeal to children, they also seem to picking up the tendencies of commensurate older-kid web lives. In other words, 8-year-old kids are getting boyfriends and girlfriends online, ht JD.

1) Club Penguin is one of several multimedia and game sites geared towards tweens from the ages of seven to twelve. Club Penguin itself has over 200 million registered users worldwide, and was purchased by Disney not long ago. And there are plenty of others: Poptropica, Wee World, Moshi Monsters, Fantage. Alongside the sheer breadth of these programs’ appeal to children, they also seem to picking up the tendencies of commensurate older-kid web lives. In other words, 8-year-old kids are getting boyfriends and girlfriends online, ht JD.

Kids pair off by asking “say 123 if u want me” and break up just as abruptly — like, five minutes later — by dropping a quick “brb” and then disappearing to another server. Boyfriends and girlfriends can do little besides chat, go to the virtual pizza parlor, play games against each other, and send heart emoticons back and forth.

This, naturally, is upsetting many parents, as The Verge writes, particularly with the modern fears of child predation—and yet, the companies running the game sites have had a hard time moderating the language while at the same time keeping their constituency:

For moderators, it’s a balancing act. If the site gets too draconian — for example, by banning the “heart” emoticon — users will rebel. If the site gets too lenient, parents will forbid their kids from playing. Most sites use a combination of semantic processing, user reporting, and human moderators in order to catch flirtation and sexual overtures, as well as things like cyber bullying and self-abuse.

[youtube=http://youtu.be/RpV87KISWsg&w=600]

Kids have responded the way kids have always responded— despite thousands of hired moderators and code crackers and word filters, they re-invent language and semantics to keep doing what they want to do. Club Penguin even sends in moderators as spies—to look into what slang is being used and refashioned—but it still seems that the love “in the igloo” is finding ways to evade.

The danger with word filtering is that you force users into using code that’s more difficult to crack, he said. “The only game is not to play. If you overfilter, you push people off-piste and now you’re into languages you don’t understand and cultural complexities for how people invent words,” he explained. “It becomes futile.”

…”This site is for younger children, and we do a lot of things to stop that sort of behavior for the audience,” he said, when asked about dating within Club Penguin. Ultimately, stopping predators from grooming children is much more important than preventing kids from pretend dating. But virtual dating still bugs parents, Estroff said, and it’s disturbing that the activity seems to flourish in online worlds made for children. By contrast, there’s little e-dating culture on Instagram, the virtual community she’s currently studying.

“It’s just the idea of these little kids,” she said. “They’re girl scouts by day and hanging out with a boy in an igloo at night.”

2) Speaking of the present (and past and future) age of kiddos, Slate is releasing a series of articles to do with the bullying issue that’s taken wave. This one, by Carly Pifer, normalizes the phenomenon. Sure, technology eases the impulsive immediacy and provokes the distance, but the heart of the matter is same. We bully. She bullied as a kid, and now she looks back on it.

My overwhelming emotions about the shallowness and brazen superficiality of my junior high years are regret and puzzlement. But I also know that I’m not entirely past all of those old rules and insecurities—though more often than not they show themselves in how I treat and judge myself, not others. I guess I deserve that.

All grown up, we Magnificents are, according to Facebook at least, a motley crew. My friend who we used to call “Big Nose” unfortunately had a nose job and is a successful accountant in San Francisco; another came out and was subsequently shunned by her mother. Another is in law school; another is milking cows for free in France. The prettiest, most popular of us still lives in the town where we grew up—doing what, I couldn’t say. Until a few years ago, I maintained a pseudo-friendship with just one of the Magnificent Seven. Our meetings were drenched in wine and fueled by her incessant need to click through album after album on Facebook, pointing and laughing at people’s miserable jobs and bootcut jeans. When I defended one wearer of said jeans as a smart, well-traveled guy who was my true friend and someone I admired, I felt uneasy, vaguely anxious. At 25, I thought I had finally moved on but obviously, less completely than I’d hoped.

3) As we get closer to Oscar time, there’s an interesting post over at The Atlantic about the many translations The Life of Pi experienced throughout the world. Also, not sure how we missed this, but a great piece from Michael Chabon on the pain-perspective of Wes Anderson’s storytelling. He makes comparison to the great, intensifying detail realist storyteller Vladimir Nabokov.

From Rushmore to Moonrise Kingdom (shamefully neglected by this year’s Academy voters), Wes Anderson’s films readily, even eagerly, concede the “miniature” quality of the worlds he builds, in their set design and camera-work, in their use of stop-motion, maps, and models. And yet these miniatures span continents and decades. They comprise crime, adultery, brutality, suicide, the death of a parent, the drowning of a child, moments of profound joy and transcendence.

Vladimir Nabokov, his life cleaved by exile, created a miniature version of the homeland he would never see again and tucked it, with a jeweler’s precision, into the housing of John Shade’s miniature epic of family sorrow. Anderson—who has suggested that the breakup of his parents’ marriage was a defining experience of his life—adopts a Nabokovian procedure with the families or quasi families at the heart of all his films, from Rushmore forward, creating a series of scale-model households that, like the Zemblas and Estotilands and other lost “kingdoms by the sea” in Nabokov, intensify our experience of brokenness and loss by compressing them. That is the paradoxical power of the scale model; a child holding a globe has a more direct, more intuitive grasp of the earth’s scope and variety, of its local vastness and its cosmic tininess, than a man who spends a year in circumnavigation.

Grief, at full scale, is too big for us to take it in; it literally cannot be comprehended. Anderson, like Nabokov, understands that distance can increase our understanding of grief, allowing us to see it whole. But distance does not—ought not—necessarily imply a withdrawal. In order to gain sufficient perspective on the pain of exile and the murder of his father, Nabokov did not, in writing Pale Fire, step back from them. He reduced their scale, and let his patience, his precision, his mastery of detail—detail, the god of the model-maker—do the rest. With each of his films, Anderson’s total command of detail—both the physical detail of his sets and costumes, and the emotional detail of the uniformly beautiful performances he elicits from his actors—has enabled him to increase the persuasiveness of his own family Zemblas, without sacrificing any of the paradoxical emotional power that distance affords.

4) Malcolm Gladwell spoke at UPenn on Valentine’s Day, about the human desire for proof. His conclusion? Just like cigarettes and black lung, no amount of scientific proof is ever really able to curb the appetite or change the direction of those who asked for it.

[youtube=http://youtu.be/EWaPXzTDEDw&w=600]

5) And on the note of direction-changing willpower, NPR’s Morning Edition talked this week about weight loss. With shows like “Biggest Loser,” it seems that (albeit termporarily) the only way we can be willed is by carrots and sticks, but how long until those carrots and sticks become nothing more than something else to give up on? Well, then, there’s Chester Demel, who is using hate to motivate his weight loss:

But the structure of the incentive matters, he says. Cawley worries that some programs may create perverse incentives to lose weight quickly but not sustainably. And giving money away may not be the best answer: Cawley’s work shows that people fight harder to shed weight if they stand to lose money.

Take Chester Demel. Peer pressure and encouragement didn’t help him stick to diets. But hate? Hate motivates. Last year, Demel pledged on a website called StickK to shed a pound every week. And if he failed, he agreed to fork over $5 to a cause he dislikes. The selection of “anti-charities” spans the political spectrum; Demel chose the National Rifle Association. When he thinks about them, “my blood boils. I get really angry,” he says.

Instead of thinking of doughnuts, Demel started hearing the theme from Rocky. Fancying himself a lean and hungry Rocky Balboa, he would scramble up five floors to his New York City apartment. He shed 45 pounds in a year. “The punitive thing works for me,” Demel says.

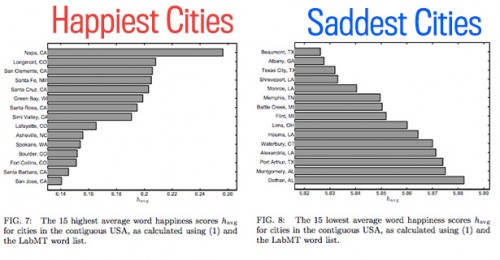

6) Here are the happiest and saddest cities in America, according to 10 Million Tweets. I don’t know what’s more indicative—the findings or the presumptions underlying the research itself. I wonder if there are still “happy” Twitterless towns around. If not, I wonder if there are “happy” towns that say the occasional swear word!

And did you hear the news about Arrested Development? A young Lucille Bluth?!

7) Last, but best, Dan Siedell’s piece over at Patheos is certainly worth the full read. In it he talks about the “starving artist” stereotype and a truer consideration of what (any) vocation means.

Edvard Munch said, “art comes from joy and pain.” And then he added, “but mostly from pain.” The myth of the tortured artist, which has a long and distinguished history, who feels more deeply, struggles with depression, addiction, and alienation puts the artist “over there” away from “us,” either on a pedestal or in the gutter. But that posture overlooks one very important reality: the artist is exactly like us. Most of our work comes from pain. We struggle with precisely the same existential problems and insecurities as Edvard Munch, we possess the same self-doubt, insecurities, and struggle with failure. Yet our vocational conversations usually prevent such admission and the important and necessary reflection that could follow.

P.S. Mockingbird has its first e-book! You can buy This American Gospel on Kindle HERE.

P.P.S. Stephen Colbert’s Abreactive Scandinavian Log:

The Colbert Report

Get More: Colbert Report Full Episodes,Political Humor & Satire Blog,Video Archive

[youtube http://youtu.be/Y0suoIRUvcw&w=600]

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply