“I’m a pessimist, in that I know it’s not going to end well. But most of my songs are spiritual at the core. I try not to be too cynical about things, because it’s too difficult otherwise. You have to be able to work your way through it – you have to be able to see what’s there, and deal with it.”

These are the words of the one and only Scott Walker, talking about the record he released in December of 2013, Bish Bosch. The arrival of new Scott Walker material is still a bit of an event – only four official albums in the last 35 years – and every time something new appears, rather than talk much about the new stuff the press takes the opportunity to give a rundown of his remarkable career. This piece is no exception.

These are the words of the one and only Scott Walker, talking about the record he released in December of 2013, Bish Bosch. The arrival of new Scott Walker material is still a bit of an event – only four official albums in the last 35 years – and every time something new appears, rather than talk much about the new stuff the press takes the opportunity to give a rundown of his remarkable career. This piece is no exception.

Scott is a typical maven. Most of us are far more familiar with the people he’s influenced than he himself. For example, one of the main factors behind both Radiohead and Blur initially coming together was their mutual affinity for all things Walker. Our beloved Jarvis Cocker is a long-time Scott devotee, and somehow even coaxed the man himself into producing the final, glorious Pulp record, We Love Life. Then there’s the executive producer of 30 Century Man, the 2006 documentary about Scott, a little guy named David Bowie. The list goes on.

So why talk about Scott Walker on Mockingbird? Well, for starters, his music is absolutely wonderful, and that’s reason enough. But two, his career has followed a path of life, death and resurrection that has virtually no parallel in the pop world. I also find his process to be fascinating, especially as it relates to the nature of inspiration and where it comes from.

Really quickly then, because every other place on the net already has their much more detailed versions of the story: Scott came to fame in the mid 60s as the singer for The Walker Brothers. They weren’t brothers, and none of them were actually named Walker–Scott was born Scott Noel Engel, the American son of German immigrants. Their sound was basically an Anglicized form of Phil Spector’s work with The Righteous Brothers, in other words, full of big emotions and arrangements and lots of echo and swelling strings, with Scott’s beautifully melancholy baritone leading the way. They experienced moderate success in the States (the immaculate “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore” was a top 20 hit in 1966), but astronomical, Beatles-sized success in Britain. People call The Walker Brothers a proto-boy band, and they’re not far off.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2eAxCVTMJ-I&w=600]

Infighting led to the Brothers disbanding in 1967, after which sensitive Scott recorded four solo records, the cleverly titled Scott 1, Scott 2, Scott 3 and Scott 4. The first two mixed his own moody compositions with pop standards and English language versions of Jacques Brel songs. The third was front-loaded with gloomy and slightly dissonant ballads written by Scott, and it succeeded in alienating a good many of his fans.

By the time Scott 4 came around in 1969, no one bought it. This despite the fact that it was much more upbeat and accessible, relatively speaking, and even had a couple of potential hit singles on it. Scott 4 is universally acknowledged as his masterpiece–a record a bit like The Velvet Underground’s debut in terms of influence, meaning that many of those few people who did buy it started bands.

The album has stood the test of time remarkably well. Others were singing about peace and love, but Scott was more interested in dictators, disease and Swedish film. The sound is all Morricone’d up–male choirs, classical guitars, ominous strings–with Scott adding hyperactive basslines and pedal steels and more drums than on almost any other record of his. The songwriting, for once, is reasonably straightforward (and unreasonably inspired); pretty much every track is a classic.

So Scott 4 is as good as the record store snobs claim. It’s also intimidating to note that he made it when he was only 25. He took some heat for including a Camus quote on the sleeve–indeed, given the subject matter and atmosphere of his last few records, charges of unbearable pretentiousness were not exactly unfounded–but if you can get beyond the existence of the quote, its content is actually quite beautiful: “A man’s work is nothing but this slow trek to rediscover, through the detours of art, those two or three great and simple images in whose presence his heart first opened.” And while one could be forgiven for dismissing the work and its author as a graven downer, that would be a major misperception (albeit one that has dogged him all along). The humor is all over the place, as evidenced here:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N-zgdGQB4S4&w=600]

When Scott 4 tanked, the perceived judgment was devastating, and Scott retreated into what by all accounts was a pretty serious drinking habit. There are a couple of great songs on the otherwise iffy follow-up, 1970’s Til The Band Comes In, but they would be his last original compositions to see the light of day until 1978. In his depression, Scott’s management and record label somehow convinced him to spend the next five or so years recording middle-of-the-road MOR standards aimed at the nostalgia crowd, with diminishing returns. To fans of his earlier work, it felt like a betrayal; the artist, for all intents and purposes, had been killed.

Yet the story goes on. Spirits and economic prospects flagging, the Walker Brothers reformed in 1975 and had a minor hit with a cover of Tom Rush’s “No Regrets.” The follow-up record failed to capitalize on the momentum, and it soon appeared as though their second coming had stalled out. This is where things get interesting again. Their record company was going out of business, so for the third “reunion” record, the boys (now men) were given free reign to do whatever they wanted, independent of any commercial concerns. The freedom, aka the lack of pressure or oversight of any kind, had a resurrecting effect on Scott, who decided that the album, Nite Flights would consist entirely their of their own compositions, the opening four of which would be the first Scott originals in eight years.

These four songs–“Night Flights”, “Shutout”, “Fat Mama Kick” and “The Electrician”–weren’t just a return to form, they represented a new vanguard for popular music, and from an incredibly unexpected source. Menacing keyboards, slightly muddled vocals, disco bass work, stabbing guitar lines, somewhat frightening and fragmented lyrics, it was a whole new energy.

Some say Scott invented New Wave in one fell swoop. I remember reading somewhere that the recordings sounded as though Scott had been secretly developing along precisely the same radical lines as (his disciple) Bowie; so fully formed was the new sound and, um, vision. Yet even Brian Eno confessed that Scott had outdone Bowie and Eno’s much-celebrated Berlin period in those paltry four tracks. Lamenting in 2006, Eno commented, “We still haven’t gotten any further.” Of course, the record didn’t sell, and the Walkers were out of a company and a contract. Scott, however, was reborn.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yELbkzAIfmA&w=600]

His subsequent releases–again, only four in 35 years–are not for everyone. In fact, the “recent” trilogy (Tilt, The Drift, Bish Bosch) is actively hard to listen to, nightmare-ishly so in places. This is because Scott hasn’t looked back, even for a second. He has continued to push the envelope as far anyone in all of contemporary music (popular or avant garde, rock or classical), and the sum of his efforts amounts to nothing less than the kind of freedom, both artistic and existential, that is only found on the other side of the death of expectation and self.

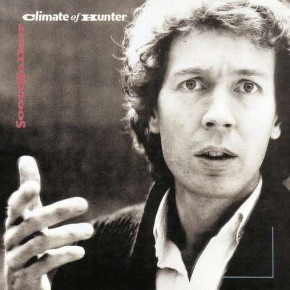

While Scott insists that there is not now, nor has there ever been, an autobiographical element to his work, it is impossible to listen to “Track Three” from 1984’s Climate of Hunter, the amazing and amazingly divisive follow-up to Nite Flights, without hearing something of what the man has gone through. The “chorus” reads “Rock of cast-offs/Bury me/Hide my soul/Sink us free/Rock of cast-offs/Bury me/Hide my soul/Pray us free.”

When asked at the time why it took so long to release new music, he spoke about needing to find the right kind of silence for the material to arrive. Scott regards his role in the creative process, in other words, as a fundamentally passive one. His music comes from somewhere else, somewhere outside of him, and it shows. Here’s how he put it in a rare interview with The Guardian last year:

What [Scott] does believe is that harmony is heightened when you have to work for it. Beauty is best appreciated buried in the grotesque. And yes, he says, there is a pessimism to his work, but the chinks of life offer hope. “That’s why I’m so puzzled when people say it’s all dark, dark, dark, whereas I think there’s a lot of beauty in it. Obvious beauty.” And in the end, he says, that’s what his music is about – the search for meaning and purpose in the wreckage. “I’m not a religious man, but it’s a longing.” For what? “For who knows. For existence itself. True existence. It’s a longing for a calling. It’s just a feeling that it might be there.” Can we all find this purpose? “Oh yes, I believe so. We just need to find enough silence and stillness to experience it.”

In the 2006 documentary 30 Century Man–for my money one of the best rock docs of all-time–Scott talks about his post-Nite Flights trajectory as involving the elimination of all personality from his music. He has ceased to care what Scott Walker has to say about anything. That man is long dead, anyway. He is much more interested in channeling the external, non-Scott source of inspiration, as precisely as possible, whatever or Whomever it may be. This means the process now consists in stripping his art of all subjective elements, leaving only those which are universal. One could argue that he is only free to embrace such an ambitious yet non-credit-seeking project because his own identity was so publicly divested in the 70s. Instead of his legendary voice, he now wants you to hear “just a man singing”.

One could argue that Scott is only free to embrace such an ambitious yet non-credit-seeking project because his own identity was so publicly divested in the 70s. Speaking with The Guardian again, which had noticed something strangely life-affirming about his work, Scott responded:

“And a lot of it has to do with… contentment might be too strong a word, but it might be to do with the fact that I’m at last able to make the records I want to make. Because I went through a patch when I was a leper, when nobody wanted to get near me.”

Obviously there is something transcendent–or, as he puts it, spiritual–to what he’s trying to achieve with his work these days. Should it go without saying that his most recent records are chock-a-block full of Biblical allusions and imagery? That those allusions have even increased as time has gone on? Probably. Fortunately, his sense of humor has not waned either (the line “There but for the grace of God goes God” being one particularly memorable example from Bish Bosch‘s “Tar”).

Suffice it to say, Scott Walker is reaching for the Almighty in about as courageous and well-respected a fashion as anyone in the musical world these days. Which also means these are not records that one can really write about; in fact, they are almost the definition of ineffability, both lyrically and sonically. But we can at least appreciate the ineluctable freedom of the man through whom they are being made. I’ll conclude with some of Scott’s own words from 2008:

How would Scott Walker describe his singular artistic sensibility? ‘Essentially, I’m really trying to find a way to talk about the things that cannot be spoken of,’ he says. ‘I cannot fake that or take short cuts. There is an absurdity there, too, of course, and I hope that people pick up on that. Without the humour, it would just be heavy and boring. I hope,’ he says, once more, ‘people get that. If you’re not connecting with the absurdity, you shouldn’t be there.’

There’s not a lot of harmony and there aren’t the thick textures I used to use. It’s generally just big blocks of sound, raw and stark. A big emotional noise.’ Another silence. ‘Essentially, I am attempting the impossible over and over, trying to find a way to say the unsayable. For some reason,’ he says, laughing, ‘that just seems to take a lot longer.’

Who knows, maybe the wait will give those of us who find Scott’s latter-day music so impenetrable time to catch up. Maybe our spiritual impairments will dissipate to the point where we too can appreciate whatever it is beyond himself that Scott is drawing upon. Even if they don’t, we can certainly “get behind” the ineluctable freedom of the man through whom these records are being made. We won’t wait forever, though. If Scott’s life and music can be trusted, the band will come in eventually.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dBMJ79ly3B4&w=600]

P.S. I thought about including a playlist for those interested in hearing some of this great man’s work, but PopMatters put together a fairly perfect list already.

P.P.S. The above was adapted from A Mess of Help: From the Crucified Soul of Rock N Roll.

COMMENTS

4 responses to “Scott Walker Is Dead, Long Live Scott Walker! (RIP)”

Leave a Reply

David, this is such a great piece. Yes, for me, those four magic songs from Nite Flights are incredibly enduring. “Shut Out” is personal fave, still played regularly by many a fine disco-not-disco dj, heard it played in London many times just a few years ago. When are you going to compile all these music essays in a single book? Or is the answer: “not until I dive comprehensively into the work of Prince”?

Really good article on Scott, I love “Climate of Hunter”. Who else from the ’60’s is doing work as good as him – or any other period after for that matter. I just love his music and what he represents.

I love everything my hero does.I am not a educated person. I know what I like and I am a child of the sixty’s (flower power an all) my the great man live and produce forever.

Beautiful voice which I felt was wasted. He was polite, shy and introverted..interviewed him in 1968 as a solo artiste .. what a waste of talent but it was his choice. Miss you!