Last time we gathered round for a Turkle Ticker we talked about the Second Life phenomenon, the use of technology to recreate identity or, at least, to use technology to impute to oneself whatever one feels one lacks. Whether it’s good looks, an interesting career, a different outlook on life, this is true not only of programs like Second Life but any social media apparatus that lends us the opportunity to present and posture something other than our very selves.

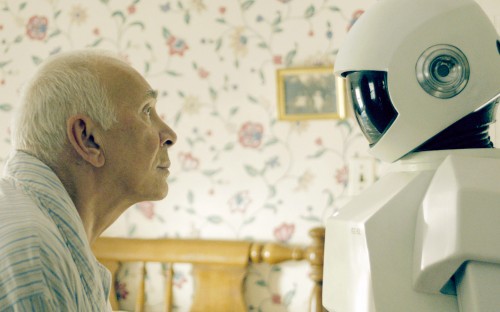

Today we look into the nature of love and caring. Is love a behavior, or an emotion, or an attitude? What do we mean when we say words like “love” and “care”? Turkle, in Alone Together, is saying that the way we’ve begun to use these words shows more than just a semantic shift—it seems to be more worrisome. Like something out of a Bradbury story, her stories come from studies in nursing homes, where Japanese Paro robots have been brought in to keep the elderly occupied. As you’ll see, the robots aren’t used just as roving pill dispensers and bath-givers, but as actual “carers.”

So, a fall 2005 symposium, titled “Caring Machines: Artificial Intelligence in Eldercare” began with predistributed material that referred to the “skyrocketing” number of older adults while the “number of caretakers dwindles.” Technology of course would be the solution. At the symposia itself, there was much talk of “curing through care.” I asked participants—AI scientists, physicians, nurses, philosophers, psychologists, nursing home owners, representatives of insurance companies—whether the very title of the symposium suggested that we now assume that machines can be made to “care.”

Some tried to reassure me that, for them, “caring” meant that machines would take care of us, not that the would care about us. They saw caring as a behavior, not a feeling. One physician explained, “Like a machine that cuts your toenails. Or bathes you. That is a caring computer. Or talks with you if you are lonely. Same thing.” Some participants met my objections about language with impatience. They thought I was quibbling over semantics. But I don’t think this slippage of language is a quibble.

The semantic distinction here, Turkle points out, is between the notion of caring as action and caring as something more interior. Caring as action, or “taking care of someone,” is a care that is disembodied to the extent that anyone can do it. Because anyone can do it, Turkle suggests, we choose that anyone to be not me. We naturally look for alternatives to “do the work of caring” while we shove off.

This is not to retranslate caring, she suggests, but to deny what it is altogether and call it something different. Love must be two persons, not because love always works in emotional reciprocity, but because there must be a “voice at the end of the line,” if you will. As you read on, if there’s no one to absorb what you’re saying with empathy, the heart of caring—as well as its residual works—are for naught.

This is not to retranslate caring, she suggests, but to deny what it is altogether and call it something different. Love must be two persons, not because love always works in emotional reciprocity, but because there must be a “voice at the end of the line,” if you will. As you read on, if there’s no one to absorb what you’re saying with empathy, the heart of caring—as well as its residual works—are for naught.

I think back to Miriam, the seventy-two-year-old woman who found comfort when she confided in her Paro. Paro took care of Miriam’s desire to tell her a story—it made a space for that story to be told—but it not care about her or her story. This is a new kind of relationship, sanctioned by a new language of care. Although the robot had understood nothing, Miriam settled for what she had. And, more, she was supported by nurses and attendants happy for her to pour her heart out to a machine. To say that Miriam was having a conversation with Paro, as these people do, is to forget what it is to have a conversation. The very fact that we now design and manufacture robot companions for the elderly marks a turning point. We ask technology to perform what used to be “love’s labor”: taking care of each other.

…But people are capable of the higher standard of care that comes with empathy. The robot is innocent of such capacity. Yet, Tim, fifty-three, whose mother lives in the same nursing home as Miriam, is grate for Paro’s presence. Tim visits his mother several times a week. The visits are always painful. “She used to sit all day in this smoky room, just staring at a wall,” Tim says of his mother, the pain of the image still sharp. “There was one small television, but it was so small, just in a corner of this very big room…I used to hate to leave her in that room.” He tells me that the project to introduce robots into the home has made things better. He says, “I like it that you have brought the robot. She puts it in her lap. She talks to it. It is much cleaner, less depressing. It makes it easier to walk out that door.” The Paro eases Tim’s guilt about leaving his mother in the depressing place. Now she is no longer completely alone. But by what standard is she less alone? Will robot companions cure conscience?

This is an interesting point, and most interesting that Tim’s support of robotic care is basically a sloughing off of guilt. In other words, the robot does his justifying for him. But, on the other hand, and as you’ll see below, what really seems striking is the utter discomfort we feel with love-unto-death. Like Tim, we can handle caring so long as its tidy, non-depressing, non-demanding. Though this may be laziness at “love’s labor,” it’s also a discomfort with sufferers and the reality of death and dying. We want love, we want to love, but we don’t want to suffer. It is here, though, as we know, where love finds its deepest meaning.

…I find that people are most comfortable with the idea of giving caretaker robots to patients with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia. Philosophers say that our capacity to put ourselves in the place of the other is essential to being human. Perhaps when people lose this ability, robots seems appropriate company because they share this incapacity. But dementia is often frightening to its sufferers. Perhaps those who suffer from it need the most, not the least, human attention. And if we assign machine companionship to Alzheimer’s patients, who is next on the list? Current research on sociable robotics specifically envisages robots for hospital patients, the elderly, the retarded, and the autistic—most generally, for the physically and mentally challenged.

…This is contested terrain. Two brothers are at odds over whether to buy a Paro for their ninety-four-year-old mother. The robot is expensive, but the elder brother think the purchase would be worthwhile. He says that their mother is “depressed.” The younger brother is offended by the robot, pointing out that their mother has a right to be sad. Five months before, she lost her husband of seventy years. Most of her friends have died. Sadness is appropriate to this moment in her life. The younger brother insists that what she needs is human support: “She needs to be around people who have also lost mothers and husbands and children.” She faces the work of saying good-bye, which is about the meaning of things. It is not a time to cheer her up with robot games. But the pressures to do just that are enormous. In institutional settings, those who take care of the elderly often seemed relieved by the prospect of robots coming to the rescue.

COMMENTS

One response to “Another Friday Sherry Turkle Ticker: Elderly Care and Nursing Robots”

Leave a Reply

Sherry’s book was good. I read it after seeing her TED talk posted here. It’s worth noting though, that her book is half robots/half social media related. I didn’t know this going in, thinking it was going to be more or less an expanded version of her TED talk, and I found myself weary of the book a quarter of the way through, having no real interest in robots, but having a great interest in social media and it’s effects on our lives.

Nevertheless, she brings up some very good points about the nature of the human soul, and the value of the human soul that is a breath of fresh air from the halls of academia. I’d recommend it for anybody, but just be warned that the book is mostly anecdotal in nature. Expect analyses strewn in bits and pieces throughout the volume.