The third installment of Blake Collier’s groundbreaking In the Event of a Cosmic Horror series. To read part one, go here. Or part two, here.

Okay, let’s just get it out of the way. Zombies automatically make Christians think of the “resurrection of the body.” And, if we are honest, it is the closest pop culture reference to this theological concept. But something is wrong. I don’t know about you, but I personally don’t want to imagine my spiritual body in the new heavens and new earth desiring ‘bwains.’ Zombies come so close to being the holy grail of Christian eschatological (end-time) analogies that we are usually willing to avoid the obvious “missing arm”: that is, why are all of the living dead, or “walking dead”, so willing to cannibalize others? Why can’t some of them be vegans? And why is any discussion of the intersection of the living dead and Christianity so willing to avoid the voraciously hungry zombie elephant in the room?

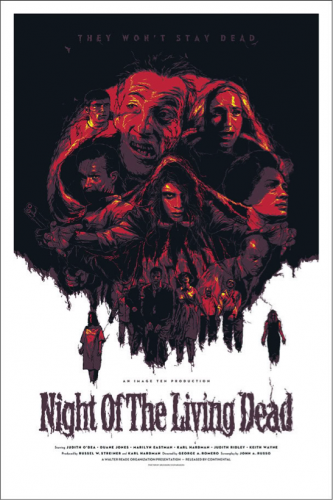

There are two films that must be, and always are, addressed in any discussion of the living dead: Night of the Living Dead (1968) and 28 Days Later (2002). The very first zombie films, of course, had to do with Haitian voodoo and mind control rather than post-apocalyptic armies of living dead. It made for a few decent films and a wide array of embarrassingly cheesy ones. It was not until 1968 that the zombie latched onto the neck of the culture with real fierceness, the reason being a small independent flick by an unknown director by the name of George Romero. Night of the Living Dead would quite literally breathe new life into a dying plot line. According to Glenn Kay, author of Zombie Movies: The Ultimate Guide:

There are two films that must be, and always are, addressed in any discussion of the living dead: Night of the Living Dead (1968) and 28 Days Later (2002). The very first zombie films, of course, had to do with Haitian voodoo and mind control rather than post-apocalyptic armies of living dead. It made for a few decent films and a wide array of embarrassingly cheesy ones. It was not until 1968 that the zombie latched onto the neck of the culture with real fierceness, the reason being a small independent flick by an unknown director by the name of George Romero. Night of the Living Dead would quite literally breathe new life into a dying plot line. According to Glenn Kay, author of Zombie Movies: The Ultimate Guide:

“[Night of the Living Dead’s] zombies are not controlled by a mad scientist or a voodoo master; instead, they follow their own will, moving as a group toward one simple and most horrifying purpose: food. These new zombies are cannibals, living off the flesh of the living (and occasionally bugs, for extra gross-out effect). If a person dies, he or she simply rises and continues the search for flesh. The living dead are disturbing, scarred, grotesque looking, and extremely hungry. . . . It is bleak—while the characters take refuge in the isolated, claustrophobic farmhouse near a cemetery, newscasts report that the dead have risen up across the eastern seaboard, offering no reasons for or solutions to the problem.” (p. 54)

Thirty-four years later, another low-budget (at least by industry standards) film would reinvigorate the sub-genre once again. 28 Days Later was successful not because it was original, but because of the deft-handed direction of Danny Boyle and a handful of talented, but relatively unknown (at the time), actors. There had been other films before 28 Days Later that used the concept of a virus or disease or plague infecting humans and transforming them into zombies, like I Eat Your Skin (1964) and Zombie (1979), but none as visceral or imaginative.

Between these two central films, one (Night of the Living Dead) hides the explanation of the resurrection of the living dead in enigma, granting the possibility of a supernatural cause, while the other film (28 Days Later) embeds its premise in modern biology, rendering only a naturalistic explanation. However, the one thing that binds both of these films and zombie films since 1968, is the apprehension of what it is to live after biological death; or, in other words, how incapable we are of making sense of the afterlife, or promise of the “resurrection of the body.”

Thacker, once again, places this human fear within the context of the cosmic horror:

“What theology implicitly admits, horror explicitly states: a profound fissure at the heart of the concept of ‘life.’ Life is at once this and that particular instance of the living, but also that which is common to each and every instance of the living. Let us say that the former is the living, while the latter is Life (capital L). If the living are particular manifestations of Life (or that-which-is-living), then Life in itself is never simply this or that instance of the living, but something like a principle of life (or that-by-which-the-living-is-living). This fissure between Life and the living is basically Aristotelian in origin, but the fissure only becomes apparent in particular instances. . . But one thing to note is that in [the living dead’s] case we have a form of life that at once repudiates ‘life itself’ for some form of afterlife. [The living dead] are literally living contradictions.” (p. 115-16)

The reason why these cinematic representations of the afterlife, or “resurrection of the body,” are “living contradictions” is because we are not, logically or rationally, able to comprehend the “living” that will be done on the other side of death. While the Bible certainly contains promises of an afterlife, there is an unknown element to exactly what that “living” will be like and what elements of “Life” will be shared between this life and that one. And when our mind fails to deliver an answer, we start to fear. If to “know” is to “control”–and a complete understanding of the afterlife defies knowledge–we therefore have no control over what is, ultimately, to happen to us after biological death.

In the midst of this cosmic horror, we create fictions, or representations, to allay our fears–hence zombies. And it is quite ironic that these zombies desire flesh. Ironic because our representation of the “resurrection of the body” desires the one thing that we, analogically, desire: the flesh. I wonder if this is our representation of the afterlife because, deep down, that is the “living” that we know; that we are not inherently good or free, but that we are controlled by the flesh (our sin), it is our hunger. In the end, in our attempt to tame our fear of death and the unknown, we reveal exactly that which is most real to our “living” now, that which is in most need of the grace that only God can provide.

In the midst of this cosmic horror, we create fictions, or representations, to allay our fears–hence zombies. And it is quite ironic that these zombies desire flesh. Ironic because our representation of the “resurrection of the body” desires the one thing that we, analogically, desire: the flesh. I wonder if this is our representation of the afterlife because, deep down, that is the “living” that we know; that we are not inherently good or free, but that we are controlled by the flesh (our sin), it is our hunger. In the end, in our attempt to tame our fear of death and the unknown, we reveal exactly that which is most real to our “living” now, that which is in most need of the grace that only God can provide.

As David Browder posed in part four of his incredible “Do You Have a Zombie Plan?” series (and, really, in the whole series):

“We feel naked in this world as we contemplate the as-yet unseen ghoul. The one we feel helpless to master. It can be the epidemic we discussed but what about when it lies within ourselves or our spouse? What about when it’s much more up-close and personal than an abstract and general fear? What if it’s a well-known ghoul that you’ve spent you entire life trying to bury with no permanent success?”

Zombie films are effective simply because they are an attempt by us to confront the unknown, the cosmic horror, which is (life after) death and, in the process of confrontation, we are forced to confront the one truth about ourselves that we are most likely to suppress: our human struggle with “flesh.” So the zombie is “a living contradiction” metaphysically and metaphorically. It is a distinct conception of the Christian idea of resurrection of the body run through a rationalized meat grinder, ultimately revealing nothing more than the negative nature of our humanity. Revealing, once again, that when those suppressed truths come to the surface, we come to find that we are not alright and that we are in need of God. He is the one who understands this life and the one that comes after. It is on Him that we must feed.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HmyQDH_PSC4&w=600]

COMMENTS

5 responses to “In the Event of a Cosmic Horror, Pt 3: The Living Dead”

Leave a Reply

I’ve been struck by the weapons that each person chooses to “kill” the zombies and the creative way “personal style” in which killing is ‘PERFORMED”.I wonder if we,I am not vicariously murdering through watching.

There is also the unfair nature of most of the killing.I mean poking holes with a tire tool into a head through a chain link fence just ought to be against the “rules”

That has always been an interesting concept to me as well. Just how much do we enjoy the slaughter and, often, sadistic approaches used to murder these used-to-be-living people. I think an element of voyeurism is apparent in most film, TV (reality or not) and everyday life. At what point are we giving in to our thoughts of sin (which we see is just as condemning as a sin that has been acted on – Matthew 5:27-30) by living vicariously through a fiction or another person’s reality? Not an easy answer to that, because it could quickly devolve into isolationism as well. And that is not what is commanded of us either.

It’s as if the image of God is what stops the slaughter of men, but as soon as that image is gone and humankind is reduced to its most base animalistic instincts, the slaughter becomes understandable. That’s what makes the early episodes of The Walking Dead so fun- it presupposes that zombies retain that Godly image. Perhaps that loss of God’s image leading to slaughter is more foreboding than I’d care to admit… because it isn’t a trope reserved for the zombie genre!

Again, very good! (I’m following your series Blake!)

Zombies really are a cosmic horror that afflicts us because of what they mean to anthropology. What is it to be man? I really liked Romer’s Land of the Dead because that question is addressed. You have men ruthessly exploiting the destitute majority to live in luxury and yet at the same time zombies are beginning to learn (!). Who is really the barbarian and who is the civilized? Or in a more existential form, who really is alive and who is dead? Is it that easy to tell? One is consumed by cannabalism and the other by injustice.

That sort of grey always exists. Just like the Walking Dead. It’s not the Infected vs. the non, rather all have the virus. The only difference is whether or not one has succumbed to it and turned.

We live in a world of shadows, not blacks and whites, and yet in the midst, the Holy One has come to make a New Kingdom out of the ash of our zombieland.

Without Christ, we think the apocalypse (literal ‘revealing’) will show us as we truly are. That is, the universe, our hearts and natures and the very fabric of reality is oozing puss. Civilization is only a game played in ruins by madmen.

Thanks be that God revealed Himself in the cross. We both see these ruins and the Light that makes all things new. Jesus Christ is Lord is not some trite phrase, it is rebellion to the seemingly inevitable Cthulu that lurks in the shadows of the cosmos. He crushed the head of the serpent.

My rambles per usual 🙂 ,

Cal