I have greatly enjoyed my copy of Mockingbird’s The Merciful Impasse: The Sermon on the Mount for Those Who’ve Crashed (and Burned), and have been especially taken with the two recordings that deal with Jesus’ clear call to passivity in the face of aggression: we are not to lash out, strike first, or vindicate ourselves in any way. “Iustitia passiva” is PZ’s term for it.

I have greatly enjoyed my copy of Mockingbird’s The Merciful Impasse: The Sermon on the Mount for Those Who’ve Crashed (and Burned), and have been especially taken with the two recordings that deal with Jesus’ clear call to passivity in the face of aggression: we are not to lash out, strike first, or vindicate ourselves in any way. “Iustitia passiva” is PZ’s term for it.

This section of The Merciful Impasse reminded me of the 1986 film The Mission which dealt with so many religious themes that it’s always seemed curious to me that director Roland Joffe’s take on his movie is that it’s not a movie about religion. He says this in the DVD commentary:

In a way this is a film that has religion in it, but it’s not really about religion. It’s about human beings. It’s about some human beings who believed deeply in religion, but it’s a movie about love, and it’s a movie about what love is. It’s a movie about the pain of love; about the vulnerability of love; about the longing for peace that love can bring or that the lack of love can take away.

So it’s not a movie about religion, and yet the Apostle John described God for us time and again using three small words: God is love. And if God is love, then a movie about “the pain of love, the vulnerability of love, the longing for peace that love can bring or that love can take away” can’t help but be a movie about God.

Yet as large as love and God loom in this movie, I want to focus specifically upon iustitia passiva as it is so beautifully portrayed. The movie deals with the conversion of the notoriously violent Guarani tribes in the South American jungle by the Spanish Jesuit Father Gabriel, who sets up a mission where the natives live, worship and are educated. Through a complicated series of events the land in question reverts to Portugese rule, and the Church, in order to avoid a violent conflict, decides to close the mission. In the scene which sets the stage, Cardinal Altamirano has told the Guarani natives that they must leave the mission and return to the jungle, to which the chief replies, “Why? This is our home. We don’t want to leave. Has God abandoned us?”

The Cardinal demands obedience and refuses to hear a word they say. He then demands that the Jesuits return with him and tells them that refusing to do so will result in excommunication. The mission is about to be forcibly destroyed by the Portuguese army.

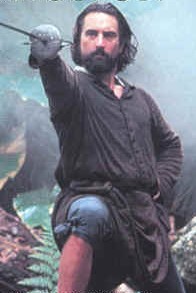

Obviously, out of love for these people, the Jesuits decide not to return with the Cardinal. But they end up taking two very different approaches to the situation. Father Mendoza, the recently converted Portuguese mercenary (played by DeNiro), makes the decision along with two other fathers to take up the sword and fight his countrymen alongside the half of the Guarani who have chosen to fight.

Father Gabriel (Jeremy Irons), however, chooses a more solitary/unpopular path, the way laid out for us by Christ, the iustitia passiva. The other half of the Guarani have chosen not to fight, but not to leave, either. So Father Gabriel stays with them, choosing their fate as his fate in a most Christ-like act of pure love.

On the morning of the pending battle, Mendoza comes to Father Gabriel and asks the Father to bless him, to which Father Gabriel responds with one of the most telling lines of the whole movie:

If might is right, then love has no place in the world. And maybe so, maybe so, but I do not have the strength to live in a world like that.

You can’t help but hear our Lord in this statement. Consider Matthew 5:44, “But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you…”

The love that Father Gabriel shows in huddling under the cross with these children of God who refuse to leave their home and their new-found faith is the love that embodies Jesus’ words in Matthew 5. It is the embodiment of the iustitia passiva, and as such it is a powerful reflection of God’s love for us.

In the last moment of his life Mendoza finally grasps what Gabriel’s words mean. This is something that one has to go back to the director’s commentary to truly realize, but it’s definitely there. During the scene in which Mendoza is dying only a stone’s throw away from Father Gabriel and the cross, Joffe tells us:

In the end it comes down to that [speaking of Mendoza’s last moment] for everybody. This is very important – a human sound cuts through… [Mendoza turns his head when he hears the sound of a crying child in the group around Father Gabriel and the cross] …and he sees the thing he loves [the cross, Father Gabriel, the people of God, the whole tender scene].

…When I was shooting the scene I began to realize that, in a way, a truth that we probably lost sight of [is] that…there is no more important moment in our lives than the moment we die, curiously enough, because it’s the way we handle that moment that will be the signature of what our life means to us In the last moments, when there is no more life to be had, don’t you want your last moment to be…honest? That’s what I discovered when I shot this scene, that we’re so frightened of death that we don’t allow ourselves to understand that it’s what gives our life meaning, too. So we run away from it, but it’s important…

What Roland Joffe saw in that moment was not what he set out to portray, but something much deeper. One can’t help but be reminded of the love of God described so beautifully in John 13.1, “Having loved his own who were in the world, he loved them to the very end.”

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PvWaD-NErlY&w=600]

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply