For Part One, click here.

For Part One, click here.

Part Two, here.

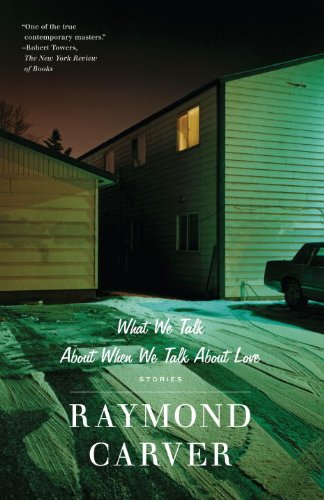

Grace has entered, and the bitterness of Carver’s main character at his wife’s beloved guest is slowly deteriorating at the dinner table. The bitterness seems more and more pointed at his wife’s worship of Robert and less and less his impression of the blind man himself. Rather, he seems to be waiting for an invitation:

They talked of things that had happened to them—to them!—these past ten years. I waited in vain to hear my wife’s sweet lips: “And then my dear husband came into my life”—something like that. But I heard nothing of the sort. More talk of Robert. Robert had done a little of everything, it seemed, a regular blind jack-of-all-trades.

When the wife is too tired to stay up, there is an excusable exit opportunity for Robert (her guest, after all!) but he chooses more drinks and cigarettes with her husband, despite our main character’s unease with this particular situation:

“No, I’ll stay up with you, bub. If that’s all right. I’ll stay up until you’re ready to turn in. We haven’t had a chance to talk. Know what I mean? I feel like me and her monopolized the evening.” He lifted his beard and he let it fall. He picked up his cigarettes and his lighter.

“That’s all right,” I said. Then I said, “I’m glad for the company.” And I guess I was. Every night I smoked dope and stayed up as long as I could before I fell asleep. My wife and I hardly ever went to bed at the same time. When I did go to sleep, I had these dreams. Sometimes I’d wake up from one of them, my heart going crazy.

After such an exchange, the reader assumes a heart-to-heart on its way, and yet the main character doesn’t do heart-to-hearts. He watches pointless television. And so they turn on the TV again and watch a special on European cathedrals. As the two continue drinking and the narrator gets more comfortable with his guest, he begins to ask some questions, particularly whether or not the blind man knew what a cathedral even looked like anyway. What proceeds from his question is an invitation to describe them himself—leading our narrator to the frustrating inability to conjure them precisely. He confesses this, and what he finds is a whole and penetrating acceptance.

After such an exchange, the reader assumes a heart-to-heart on its way, and yet the main character doesn’t do heart-to-hearts. He watches pointless television. And so they turn on the TV again and watch a special on European cathedrals. As the two continue drinking and the narrator gets more comfortable with his guest, he begins to ask some questions, particularly whether or not the blind man knew what a cathedral even looked like anyway. What proceeds from his question is an invitation to describe them himself—leading our narrator to the frustrating inability to conjure them precisely. He confesses this, and what he finds is a whole and penetrating acceptance.

I said, “Truth is, cathedrals don’t mean anything special to me. Nothing. Cathedrals. They’re something to look at on late-night TV. That’s all they are.”

It was then that the blind man cleared his throat. He brought something up. He took a handkerchief from his back pocket. Then he said, “I get it, bub. It’s okay. It happens. Don’t worry about it,” he said. “Hey, listen to me. Will you do me a favor? I got an idea. Why don’t you find us some heavy paper? And a pen. We’ll do something. We’ll draw [a cathedral] together. Get us a pen and some heavy paper. Go on, bub, get the stuff,” he said.

…He found my hand, the hand with the pen. He closed his hand over my hand. “Go ahead, bub, draw,” he said. “Draw. You’ll see. I’ll follow along with you. It’ll be okay. Just begin now like I’m telling you. You’ll see. Draw,” the blind man said.

So I began. First I drew a box that looked like a house. It could have been the house I lived in. Then I put a roof on it. At either end of the roof, I drew spires. Crazy…I took up the pen again, and he found my hand. I kept at it. I’m no artist. But I kept drawing just the same.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply