When it comes to impossible commands, indeed commands which by definition backfire, “seize the day” is right up there with “don’t worry”. Meaning, if we’re able to get beyond the immediate (and at this point pretty hackneyed) Dead Poets associations, telling someone to “seize the day” rarely inspires them to do so. More often than not, it draws their attention to all the ways they’re not doing so, the things they’re missing out on–even at this very moment! Which doesn’t mean it isn’t better to live in the present than spend our time ruminating on the past or fearfully fantasizing about the future. It absolutely is. But just like the injunctions to be spontaneous or humble, the moment we “try” to live in the moment, we have effectively removed ourselves from the present. A Christian might be on more solid ground with an adjusted slogan of “receive the day”. That presents problems of its own, though.

When it comes to impossible commands, indeed commands which by definition backfire, “seize the day” is right up there with “don’t worry”. Meaning, if we’re able to get beyond the immediate (and at this point pretty hackneyed) Dead Poets associations, telling someone to “seize the day” rarely inspires them to do so. More often than not, it draws their attention to all the ways they’re not doing so, the things they’re missing out on–even at this very moment! Which doesn’t mean it isn’t better to live in the present than spend our time ruminating on the past or fearfully fantasizing about the future. It absolutely is. But just like the injunctions to be spontaneous or humble, the moment we “try” to live in the moment, we have effectively removed ourselves from the present. A Christian might be on more solid ground with an adjusted slogan of “receive the day”. That presents problems of its own, though.

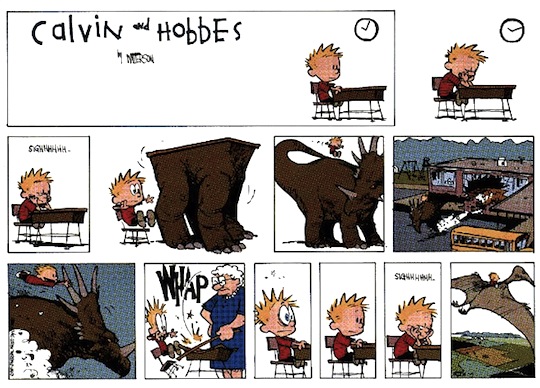

Bottomline is, left to its own devices, human nature seems to want to live anywhere other than the present–“prone to wander” is how the hymn puts it–even when we know full well that such thinking has a largely negative effect on our well-being. Chalk it up to Original Sin or cast it as a downside of our capacity for abstract thought, whatever you choose, the implications are anthropologically and therefore theologically relevant. A report in Medical News Today (and a follow-up article by John Tierney in the NY Times) put this dynamic in amusingly scientific terms, specifically the phenomenon of “mind wandering,” which they define as the uniquely human “ability to think about what is not happening.” When directed at the future, “mind wandering” serves almost as mental shorthand for anxiety/fear; when geared to the past, for guilt/anger. Regardless, it seems to be a pretty accurate description of how faithlessness actually functions in our day to day. Some real humdingers of understatement here, ht JD:

The research, by psychologists Matthew A. Killingsworth and Daniel T. Gilbert of Harvard University, is described this week in the journal Science. “A human mind is a wandering mind, and a wandering mind is an unhappy mind,” Killingsworth and Gilbert write. “The ability to think about what is not happening is a cognitive achievement that comes at an emotional cost.”

Unlike other animals, humans spend a lot of time thinking about what isn’t going on around them: contemplating events that happened in the past, might happen in the future, or may never happen at all. Indeed, mind-wandering appears to be the human brain’s default mode of operation.

“This study shows that our mental lives are pervaded, to a remarkable degree, by the non-present.”

Killingsworth and Gilbert, a professor of psychology at Harvard, found that people were happiest when making love, exercising, or engaging in conversation. They were least happy when resting, working, or using a home computer.

“Mind-wandering is an excellent predictor of people’s happiness,” Killingsworth says. “In fact, how often our minds leave the present and where they tend to go is a better predictor of our happiness than the activities in which we are engaged.”

Time-lag analyses conducted by the researchers suggested that their subjects’ mind-wandering was generally the cause, not the consequence, of their unhappiness. “Many philosophical and religious traditions teach that happiness is to be found by living in the moment, and practitioners are trained to resist mind wandering and to ‘be here now,'” Killingsworth and Gilbert note in Science. “These traditions suggest that a wandering mind is an unhappy mind.” This new research, the authors say, suggests that these traditions are right.

I’m reminded of those wonderful words of Anne Lamott’s, “Forgiveness means giving up all hope for a better past.” You could even add “or all fear of a worse future,” as the case may be. Which may sound like an equally impossible command, but hey, perhaps this is why the news that we are the objects (rather than subjects) of divine forgiveness–past, present and future–is so good.

Then again, I wonder if it’ll be as encouraging a word next week. You know, anything could happen.

COMMENTS

2 responses to “All Who Wander Are, um, Lost”

Leave a Reply

That's all great up to a point, but on the other hand, it is certainly invaluable to our existence that we are able to contemplate theoretical future possibilities, as well as learn from the past. We might not be happiest during those moments of contemplation, but human flourishing isn't possible without them. And Christians of all people should know that quite well.

Jameson! I thought you were gone–nice to see you back:)

You're completely right: Christians, of all people, should have a particular view of the value of contemplation that learns from the past with an eye to the future; however, this appreciation is shaped (determined?) by the cross in a way that differs from that of non-Christians.

As you well know, Christianity, by way of the incarnation, affirms the reality of linear time in a radical way (among world religions, that is) by claiming that God is at once immanent and transcendent. This means that, for the Christian, the past, present and future, while wholly secured by Faith, is redeemed, reanimated, restored, etc (but beginning with "r")—also otherwise known as a grateful sense of fearless freedom and trust (ideally)

I could be mistaken, but I think this is why Dave characterized this article as a prime example of faithlesness.

Thanks for the comments!

Fondly,

Jady