To kick off “Pixar Day” here on Mockingbird, we proudly present part two of Jeremiah Lawson’s AKA Wenatchee the Hatchet’s exclusive essay “Toy Story as a Trilogy of Heroic Repentance.” The first part dealt with the nature of conflict in the Pixar masterwork (internal, not external) and Woody’s role in the first film as a kind of prophet. This time around, WTH covers the central struggles in Toy Story 2&3, looking at identity, love, repentance and the lack thereof [spoiler alert]. As a side-note, since the essay was conceived as a whole, be sure to check in for the stunning conclusion next week, i.e. this one constitutes something of a transition between the intro and the conclusion–the body paragraphs, if you will.

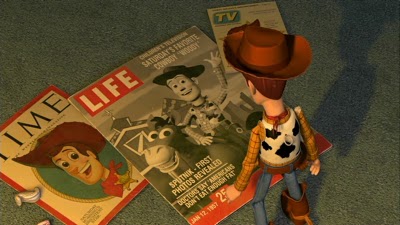

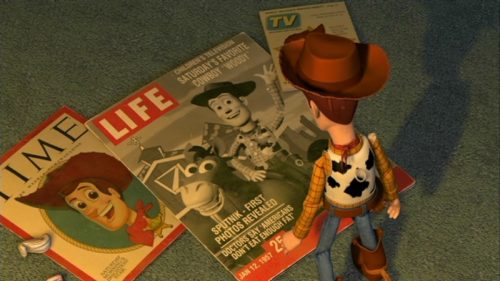

The central struggle in Toy Story 2 is not that Woody will be replaced (by Buzz), but that Andy will cast him aside if he is broken. Andy is growing up and may no longer want to play with him. So Woody’s great temptation in Toy Story 2 is to trade in his identity as Andy’s toy (and the friend of Buzz and the other toys) for an alternate one: a rare collector’s item. As we will see, the “whoever wants to save his life will lose it and whoever loses it will save it” (cf. Matthew 16:25) theme is once again powerfully present.

This time around Buzz plays the prophet role, reminding Woody of his real identity and who really loves him. Woody, having seen how his fears and envy caused so much harm in the first film, obviously does not take very long to have a change of heart. What tempts him is vanity or envy but his capacity for empathy. His empathy for Jessie’s loss makes him want to stay with the Roundup gang. It looks right – like the right decision – but in truth, the path that appears to be right is a life of living behind glass and never being loved again. Buzz says, in so many words, there is a way that appears right but its end is ultimately death. Woody is quickly convinced and realizes that he has chosen a falsely. He repents, offering Jessie and Bullseye the opportunity to join him and return to Andy’s house.

Of course, The Prospector won’t have this and lays bare his motive: he hated spending decade after decade watching every OTHER toy get played with while he collected dust on a shelf. The envy that nearly destroyed Woody has completely consumed the Prospector and in the end, when the chips are down, his true character is revealed. The Prospector represents who Woody was becoming in the first film and what that it would look like if Woody had not turned from that path. What appears to be a punishment for the Prospector at the end of Toy Story 2 could, in an open-ended story, turn out for his salvation. We are not told what the ultimate fate of the Prospector is, but since the central conflict in a Pixar film is always internal, it is far less important to dispatch the titular villain to his or her death than it was/is in most Disney films.

By the third film, Woody is completely reconciled to Andy’s faithfulness and goodness. The new challenge to his role as favorite toy/prophet to the other toys is different. He must remind the other toys of the risk of eventually being shelved or given away. Woody, as a toy who has been in the family for at least two generations, is not going to face this fate and his friends know it. The other toys don’t trust that Andy will be so generous to them and choose a life at a daycare. Woody’s new conflict may now finally be an external one, but it is not necessarily with pro forma adversaries. Instead, it is with his own friends who refuse to believe him when he urges them to put their faith in Andy’s goodness and generosity. Once again, Woody acts as a kind of prophet.

When the scriptures say that perfect love casts out fear we have a useful set of stories for all ages that explore this “accidentally on purpose.” What allows Woody to face the terrifying possibility of being lost or replaced is not that he does not fear those things but that he ultimately believes that Andy’s kindness and generosity will not put him in a position where that happens. He does, however, end up in the pit of death because he refuses to give up on his friends. Rather than elaborate on the plot points of TS3, I will merely summarize: the end of Toy Story 3 reveals that the cast-off and thrown away toys are the ones through whom salvation arrives. Woody and his friends are saved by toys that were thrown to the trash heap. The toy who reveled in his power to be free of any need for a child’s love and scoffs at the mercy offered to him even by those he sought to destroy is consigned to the grill of (Sid’s) truck hurtling down the freeway. Lotso never realizes that the very children he abominated after his owner replaced him were the only people who were truly preserving the fragile dominion he had fashioned for himself.

Next up: Part Three, in which we put the pieces together, both personally and in light of Pixar’s other films, as well as the final word on villainy and identity.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Toy Story as a Journey of Heroic Repentance, Pt 2: Prospectors, Prophets and Bears, Oh My!”

Leave a Reply

Absolutely wonderful. And I'm crying over the ending of TS3 all over again…