I recently caught part of the March 31 debate between Bart Erhman and Craig Evans on the reliability of the Gospels. While listening to Dr. Ehrman drone on in his typical, dated, liberal textual criticism of the Bible, something struck me: Dr. Erhman has completely ignored the Rashomon effect.

I recently caught part of the March 31 debate between Bart Erhman and Craig Evans on the reliability of the Gospels. While listening to Dr. Ehrman drone on in his typical, dated, liberal textual criticism of the Bible, something struck me: Dr. Erhman has completely ignored the Rashomon effect.

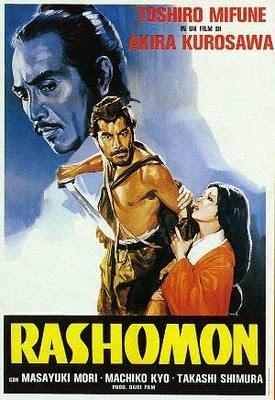

Dr. Ehrman’s argument is basic (and more than a little sophomoric): that the Gospel writers contradict each other in some of the things they record Jesus saying and doing, and so these discrepancies mean that none of the events recorded in the Gospels can be trusted. But Ehrman was apparently never exposed to Akira Kurosawa’s 1950 cinematic masterpiece, Rashomon, or he would understand exactly why those discrepancies exist.

In Rashomon, a concrete event is recorded through the eyes of four different eyewitnesses (see the connection already?). The event that occurs is a crime: the murder of a man and the rape of his wife in a forest grove. As the story unfolds, each witness gives a different account of what occurred because each is drawing from his or her own human perspective.

This idea was so powerfully portrayed in Kurosawa’s film that the experience of this phenomenon in criminal investigation has come to be named for the movie. Investigators call this the “Rashomon effect”, which describes the effect of the subjectivity of perception on recollection, by which observers of an event often produce substantially different but equally plausible accounts. The point for investigators is that the truth is in the amalgam of the individual accounts.

Applying the Rashomon effect to the Gospel accounts, it’s easy to understand why Mathew, Mark, Luke and John tell the story differently. This is merely the effect of the subjectivity of perception on the individual recollections. This does not mean that the event they record is not absolutely and concretely true. It simply means that the truth is in the amalgam of the accounts, in which all seek (in spite of human limitations) to record one concrete event: that of God himself coming down from heaven to die in our place for our sins and thereby defeat death and reconcile us to God.

So the little differences in the Gospel accounts merely highlight our own human limitations in recording an event so overwhelming that 2,000 years later we still struggle to fully grasp its wonder. If we simply apply the basic investigative principal taught to every criminal investigator in their most basic course studies, we find that the amalgam of the accounts yields the brilliant and unavoidable truth of a very concrete event.

Sign up for the Mockingbird Newsletter

COMMENTS

28 responses to “Bart Ehrman and the Rashomon Effect”

Leave a Reply

Thanks Jeff. Really nice post.

What so many people nowadays don't realize is that it didn't take 2000 years for the church to consider the question of what Luke Timothy Johnson calls "the diversity of witness" in the NT.

The early struggles over canon included a very specific internal debate, started by Marcion, over this issue. Marcion, like Bart Ehrman, didn't like the way the Gospels contradicted each other (e.g. on the Empty Tomb accounts). So he produced one edited harmonized version.

But the church finally decided — very deliberately — against Marcion and in favor of a diverse witness. We don't need Ehrman to bring this up — we thought this issue through a long time ago.

The other thing we don't realize today is the vast extent to which ALL OF US (conservatives and liberals alike) are heirs to a JOURNALISTIC paradigm of reading and processing narrative, a paradigm which didn't really exist until the 1700s.

Before then most people operated with a different sensibility, in which (say) the four Gospel stories existed as organic living breathing entities in their own right and to be experienced as such — it wouldn't have occured to them (except rare cases like Marcion) to treat them as things that could be cut into pieces and reassembled, like Frankenstein's monster.

Nowadays of course we do think that way — a news story is a sequence of facts that can be pulled apart. And don't get me wrong, there's some real advantages to that paradigm, some great things you can do with it. But it's not the only way of approaching narrative and testimony and because we are all of us so deeply unmeshed in it we have no way to grasp that there are other ways to read.

Really great post, Jeff. Lots to think about. StampDawg, I would love to hear a little more about this "other way" of reading vs. the "journalistic paradigm." When you say that early readers would have seen the gospels as an "organic living breathing entities," do you mean they saw them as divinely-created, thus perfect and complete and above human scrutiny? I'm sure it's because I'm so "deeply immeshed" in our contemporary way of reading, but I'm not quite sure I understand why early readers wouldn't have been curious about the discrepancies…

Great post, Jeff, and great comment by Mr. StampDawg. Those who take a "liberal" approach often conclude that because there are factual differences in the gospel accounts of the resurrection, then this must mean that they are not to be taken "literally" and that only the ignorant and spiritually wooden-headed do so. On the other hand, many who would defend Biblical "inerrancy" go to convoluted lengths to attempt to reconcile all factual differences in the gospel accounts, based on the presupposition that if it is "God's inspired Word" it cannot, by definition, have discrepancies, period. I think both views miss the important point made by Stampy, that God's idea of what we need in terms of a factual account of the resurrection may not be consistent with our idea of what God should have given us. God has a way of not playing by our rules.

Great question, Margaret. It's hard to answer because I really meant it when I said that we are ALL heirs to a certain way of processing narrative. That includes me!

C.S. Lewis talks about this a lot. I trust him because before he was a Christian he was a serious scholar and lover of literature and story — from ancient Greece through the middle ages through Shakespeare and into the modern period. He emphasizes how important it is to get inside the minds of other people when you are trying to read their stuff.

His chapter "Horris Red Things" in MIRACLES touches on some of this.

MC Hammer (in this thread) also hits very much on what I was thinking.

One of the treasures from the Anglican tradition is this amazing prayer from Thomas Cranmer:

“Blessed Lord, who hast caused all holy Scriptures to be written for our learning: Grant that we may in such wise hear them, read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest them, that by patience and comfort of thy holy Word we may embrace, and ever hold fast, the blessed hope of everlasting life, which thou hast given us in our Saviour Jesus Christ. Amen.”

There's a richness and (in the words of Fitz Allison) a unity of thought and sensibility that would have prevented that being written 200 years later.

I think I see what you're driving at, SD… It's as if the holy Scriptures, which the Lord has "caused to be written" have a supernatural power to nourish and guide that transcends mere fact or reportage. That's how they work for me, anyway… but they DIDN'T work that way before my conversion, back when I used to pick them apart for veracity and historicity. It took a change of heart on my part before the "deeper magic' kicked in and my whole perception changed. Or maybe it just seemed that way… I guess it was actually the deeper magic that changed my heart, not vice versa… ? I'm too weak on my theology to hang with you guys 🙂

Jeff,

Don't disagree with your main point, but I think dismissing Ehrman as a liberal theologian is a mistake. I've read his Misquoting Jesus book and, while I don't remember all the details, he does raise some very tough questions that we need to address. One that I particularly remember is something that I never considered: the possibility of transcription errors throughout the early days of the Gospels. When much of our theology is based on single words in Scripture, it is crucial to make sure we have the words right. I have no good response to this possibility, but it does seem like a valid criticism by Ehrman and one that I have no good response to.

Joe, the possibility of 'transcription errors' is something I have pondered pretty regularly for years. Since the gospels were written after the death of Christ (and some by those who didn't know him), it seems more likely that there WOULD have been errors than not. UNLESS… divine guidance ensured that every word was just so. And even then, some of it is cryptic enough that there's plenty of confusion about how to interpret the text… so we have to rely on divine guidance there, too. In short, it seems to me that the only way to understand these texts is by relying on God to reveal their truth TO us. We can't glean it by our own powers. I can't, anyway.

Guys, I apologize in advance for the length of this comment, and I'm sorry if it sounds harsh.

I tried to be generous in my post, but I want to be clear on something: I don't simply dismiss Ehrman as a liberal theologian. I dismiss him completely and absolutely as a theologian or scholar of any shade or stripe. He is no more a scholar or theologian than I'm an elephant in the circus.

There really is nothing new under the sun, and Ehrman's so-called "new scholarship" is simply a regurgitation of garbage that was refuted by biblical scholars years ago, and in some cases centuries back. As Stamp put it, Christianity moved on long ago.

Among other things, regarding Ehrman's alleged transcription errors, the actual surviving manuscripts simply don't support his point. If one applies the same tests to the Gospels that scholars apply to any document from antiquity, Ehrman's alleged scholarship falls apart.

One such test is called the bibliographic test, in which one considers how many ancient manuscripts have survived and do they all say the same thing.

Here are some facts to consider: For Aristotle there are 49 surviving ancient manuscripts. For Julius Caesar there are 10, for Plato there are 7, for Tacitus there are 7, and for Thucydides there are 8. But for the New Testament, and I'm speaking here of the really old manuscripts, more than 5,000 have been cataloged. Go out to 1100 AD and we have over 24,000 manuscripts, and guess what: they all say the same thing!

But theres more. The ancient church fathers loved to quote scripture, and there are literally reams and reams of surviving documents written by them: their sermons, lectionaries, letters to their churches, and all of these include whole cloth quotations from scripture.

In fact, there is so much scripture quoted by the church fathers that J Harold Greely has actually proven that if you use just the surviving writings of the Church Fathers up to 325 AD, the time of the Council of Nicea, and if none of the ancient copies of the New Testament had survived, one could reconstruct the entire New Testament from the writings of these church fathers, with the exception of 11 nonessential verses. And all of the quoted scripture in the writings of the church fathers matches the surviving manuscript evidence.

The veracity of the surviving manuscript evidence to support the New Testament as we have it today is such that, if you were to consider the surviving New Testament manuscripts to be a building the height of the Empire State Building, and the next best attested ancient work to be another building standing next to it, that other building would only be a five-story building by comparison.

Kind of shoots a hole in Ehrman's scholarship, don't you think?

It really doesn't though. We're not talking about the same type of document as Plato or Socrates or anything else. We are talking about the Holy Scriptures. You can apply the same tests as you do to normal historical documents, but it kind of does a disservice and doesn't recognize the importance we hold to the Scriptures.

In your rebuttal to Ehrman, you really didn't disprove his point. Just because the manuscripts we have of the Bible are better than almost anything else, doesn't mean that they are EXACTLY what was originally put down on paper by the Gospel writers. That inherent fact is something that I think we need to come to grips with and something that I have struggled with. At this point, I recognize that there are going to be human failings in what we have now, but I still believe that God has worked His way into the current Gospels. I think it would be a mistake to not recognize these mistakes just because it's better than other historical documents.

The real important question is whether the words of the Bible themselves are the things we have faith in. The clear answer is no- we have faith in the crucified and risen Saviour of the world.

textually speaking, the secondary question is whether any of the scribal mistakes offer fundamentally different understanding of Jesus. Again, the clear answer is no.

Jeff Hual is THE REAL HAMMER!!!What is striking to me about the gospel texts is the bareness and lack of elaboration on events and "sayings" that seem to scream for "comment" or "explanation" or "spiritualization" ( as attested by innumerable boring, 45 min. sermons). This type of addition usually happens to stories that are passed down over generations, but the gospels have very little of this, and still read more like Hemmingway than like Faulkner, thanks be to God.

PS to Margaret (who said that maybe she is "too weak on my theology to hang with you guys.")

You SILLY! Your thoughts are always a help to everyone here. In a major fashion.

If you are willing to hang with us we are way lucky.

Jeff, thanks for the long post. I didn't know all that, and it's VERY helpful and encouraging to me.

Todd, would you mind elaborating on this comment: "textually speaking, the secondary question is whether any of the scribal mistakes offer fundamentally different understanding of Jesus. Again, the clear answer is no"… ?

I have several friends who consider themselves "Christians," but they aren't sure they believe in the resurrection of the body or the divinity of Christ. And they don't think it matters. When they read "I am the way and truth and the life," they hear "I am the EXAMPLE of the way and the truth and the life…" They see Christ more as a teacher and an example of perfect living than as a supernatural "savior." It's a very different understanding than the one we embrace here at Mockingbird, and yet I absolutely see how they came to that understanding reading the same scripture I read…

Not sure where I'm going with this, but it seems tangentially related 🙂

Actually Joe, we are talking about historical documents when we speak of the Gospels. That's what they purport to be: third person historical accounts of the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth.

And if we consider them for a moment not as Holy Scripture but simply as history, my point is that they actually do stand up well as historical documents. Once they are proven as reliable history, they then turn out to be so much more, but first they must be proven as history, because Christianity stands or falls on the basis of a concrete historical event.

And my point is that the Gospels do hold up as historical accounts when you apply the same tests to them that are applied to any historical document from antiquity, and Dr. Ehrman is simply ignoring the preponderance of evidence.

So although Ehrman raises questions, I don't necessarily think that they're good questions. This stuff he's asking was put to bed long ago by generation upon generation of excellent biblical scholarship. It really is that cut and dry.

And thanks, StampDawg 🙂

Margaret I just think this is a marvelous issue you raised — people who self-identify as Christians but who "see Christ more as a teacher and an example of perfect living than as a supernatural 'savior.' "

That's a really common perspective and one I'd love to see us chat about in this thread (charitably guys!). Indeed, because it is so common that's why it's important to talk about. We want to find ways to understand and reach these folks.

I also totally agree with Todd's post — I hope he can spare time to give you more of a followup to it.

Hey Margaret, my comment was more directed at the specific places where the old texts differ from one another instead of, more generally, the texts themselves.

But you've tapped into a very "hot" issue right now culturally. The issue is, "from where is meaning derived?" The old postmodern approach would say that texts themselves are ambivalent or they have no real meaning in themselves. This is the world of Jackson Pollock – meaning is what you bring to it.

this approach must be rejected on several grounds, but with regard to the biblical texts themselves, they were written to convey a specific truth "that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name."

It's certainly possible to see the texts in a different light (economic, 'historical' political, whatever I make of them, etc.), but this is to row upstream against the current of the text. The text itself demands a certain interpretation- a highly personal interpretation to be sure, but one whose only appropriate response is Christian faith.

Guys, and especially Joe, I'm sorry if I came off as abrasive. I'm under the gun here at work and trying to reply between emergencies (literally!) so that first comment was very much off the cuff. Did not mean to be a "hammer". Please excuse me.

Great comments from everyone, thanks to Stamp, MC, and Todd for your insights, thanks Joe for raising questions, and Margaret, I have to say am so glad you comment here!

.

Margaret, I am gonna repeat your really great question again, cause it's so far up in the thread already. You write:

I have several friends who consider themselves "Christians," but they aren't sure they believe in the resurrection of the body or the divinity of Christ. And they don't think it matters. When they read "I am the way and truth and the life," they hear "I am the EXAMPLE of the way and the truth and the life…" They see Christ more as a teacher and an example of perfect living than as a supernatural "savior." It's a very different understanding than the one we embrace here at Mockingbird, and yet I absolutely see how they came to that understanding reading the same scripture I read…

I see two ways of tackling that, from the top-down or the bottom-up, both of which are important.

Top-Down. In talking to your friends I'd be interested in hearing more about what they think of the four Gospels. If they view them as fairly reliable (though possibly in disagreement on minor details — e.g. the exact length of Jesus ministry, the precise ordering of events, the exact number of angels present at the Empty Tomb, etc.) then I'd need to understand better how they see Jesus as such a good and wise man, and yet so profoundly wrong about himself. Because much of his teaching is about himself — he claims to be God both explicitly (I and the Father are one) and implicitly (as the One who can forgive sins). And he explicitly teaches that his purpose on earth isn't chiefly to give us better advice on how to be good, but to suffer and die at our hands in order that by his blood he might somehow "stand in" for us as sinners. C.S. Lewis's old Trilema of Lunatic, Liar, or Lord is valid here.

If, on the other hand, they view the four canonical gospels as extremely unreliable, and much of what Jesus is said to have said and done in them never happened, then I'd want to understand who the Jesus is they believe in and where they get these teachings from. I'd also want them to consider whether possibly they weren't just making up a Jesus that was very convenient for them — choosing a few teachings they liked, imagining him to be this rather than that, etc. Which is fine actually — I do that with Confucius and JS Mill and Lao-TZe and Thomas Jefferson and Plato and for that matter the guy who pumps gas down the street. They all have something to say and I can get some good ideas from all of them. But I do not call myself a Jeffersonian or a Confucian and certainly do not gather with like minded people to worship those guys.

Continued from above…

Bottom-Up. If your friends see see Christ more as a teacher and an example of perfect living than as a supernatural "savior", it may be worth looking at the human condition with them. A phrase I learned from some of the folks at MB, when one is in dialogue with folks stressing Jesus as moral example (btw — some of these folks are conservative Christians), is "How is that working for you?" I find that an incredibly helpful question. They are right that Jesus is an example of perfect living. How is that working for them? Do they find that in life that this what they need — just another bit of good advice? Do they find that they are effectively living more and more holy lives every month?

Another question to ask: suppose a movie was made of every inner thought and emotion and desire they've had for the last year, along with actions they did (especially those in secret) and then it was shown in a loop on Times Square and on the web — with their name and address below it, along with contact info for their friends and family — would they be pleased? How many of them would be so deeply mortified that they'd kill themselves rather than have it be shown? How is Jesus's moral example working in practice for them — is it really aiding them to get better?

Obviously we are going to get back here to MB's interest in the bound will and the stricken conscience and so on. We find, and we find the NT's testimony in agreement, that more and better advice about what to do isn't what we need. We need Someone to forgive us for what we are.

Nevertheless I find that some people do seem to feel that they are good people and they are steadily getting better. They don't have an anguished conscience. And for these folks (and I may just be being lazy here) I tend to feel that they are probably right in not going all in for the Jesus as Savior thing. My feeling is: ok, let me know if that changes. Right now you are right, the story and the One I know doesn't really have anything to speak to you.

But I still would express some slight confusion over why they want to go to church and be Christians. I just don't see exactly what the point is of that for them. My feeling is they could do a lot better by sleeping in Sunday, reading the NY times over coffee, volunteering for some local nonprofits and reading some self-help books and books of wise teachings. The whole church and body and blood thing seems like a bad use of time.

I caught a bit of an interview with Ehrman today, an old interview in which he's discussing his premise in "Misquoting Jesus", and I have to say categorically that his premise is false.

Ehrman asserts that we don't have the original manuscripts of the Gospels, which scholars call the "autograph copies". That's true. We don't have Mark in Mark's own hand. There are actually no surviving autograph copies of any documents from antiquity.

But then Ehrman goes into this fantasy land in which imaginary scribes were purposefully changing the manuscripts every time they were copied. There is absolutely no basis for this claim. I think I already addressed that in my comment about the "manuscript test".

Ehrman's assertion about the autograph copies reminded me of another common test that scholars apply to documents of antiquity, the bibliographic test, which takes into account the length of time between when an ancient author actually wrote his work and the earliest surviving manuscript copy.

What we’re looking to see in the bibliographic test is if the time gap is big enough for there to have been major revisions that the author never intended. And bear in mind that there are no surviving original copies of any document from antiquity. All we have to go on is the manuscript copies.

So consider the following bibliographic evidence, using the same documents of antiquity I used in the manuscript test: the time gap for Aristotle is 1,500 years; for Julius Caesar it’s over 1,000 years; for Plato it’s about 1,200 years; Tacitus is 1,000 years; and for Thucydides about 1,300 years.

By contrast, the time gap for the Gospels is only about 200 years at the most and in some cases only a little over 100 years. And these early manuscripts support the text as we have it today.

The earliest of these gospel manuscripts (that's more than just a shred) is the Bodmer Papyrus, dating to about 130 AD and containing most of the Gospel of John. Then we have the Chester Beatti Papyri, circa 200 AD, which includes major portions of the New Testament. Then we have the Codex Vaticanus from 325 AD, which is a complete copy of the entire Bible. And beyond these manuscripts we have the writings of the early church fathers with their whole cloth quotations from Scripture.

All of these manuscripts corroborate each other, and all match with the text as we have it today. Ehrman's "thousands of manuscripts" that have been changed by scribes so that they contradict each other simply don't exist!

If you combine the bibliographic and manuscript evidence, the truth that you find is that the surviving manuscripts are actually quite early, and from the early manuscripts all the way to today, everything matches with the exception of what today would be akin to typing errors.

And consider this: if I make a typing error as I copy something (which I make all the time), you still know what I'm trying to say. The texts would still be considered to match.

That's my answer to Dr. Ehrman. Sorry it was so long, but this is a subject that I wrestled with, and these are the answers that I found. And I'm not a scholar. So if I can find this stuff (which is pretty elementary), why can't Dr. Ehrman?

Jeff,

Thanks again for writing this post. I wanted to assure you that you did not come across as a hammer or what not. I have appreciated the chance to talk/write/post about this topic and have greatly enjoyed our dialog.

That being said, I wanted to clarify my opinion on this issue rather because I feel like we're starting to talk past each other. First off, I am no Ehrman disciple. I believe that the Gospel and the Bible are the inerrant Word of God and that they tell us the truth about God. I cannot, however, disagree with Ehrman's point that the Scriptures have been changed since they were originally written. As you mentioned earlier, there are thousands of manuscripts that were written without the benefit of copy and paste or Xerox machines. And I certainly cannot begin to guess at people's motivations for making these changes (although I generally think most of these changes were inadvertent). This belief comes from someone who needs to use an eraser for every single line of notes he takes.

However, I firmly believe that God works through our human imperfections to achieve His will and that includes in His Scriptures. God did not come down and write the Bible, but He did inspire and guide its human writers and He would not allow what we have now to be inaccurate as to His will. I came to think about this because of Ehrman's book and I appreciated it. Engaging that concept was very helpful and I found that I was not threatened by the possibilities that he presented because I believe what we have today is the truth even if it's different than what was originally written. I cannot deny, however, that there have been changes at some point to the Scripture and I don't think anyone can.

Wow. Just got back here, and I am LOVING all the commentary! StampDawg, I wish you lived close by. The questions you ask beg a long discussion over a bottle of wine 🙂 But let me just say, briefly (since it's time for this Mary to don her Martha cap) that I have friends who would fall into all the categories you raise. I need to reread your excellent post and ponder it for a while, but I'll get back to you…

I just want to thank you smart, lovely people for letting a deeply curious but fairly uneducated neophyte sit at your feet here on Mockingbird. What a gift!

Jeff, A "Hammer" can be a good thing 🙂 Being a "hammer" is NOT incompatible with grace and love. Luther was a hammer if there ever was one!!! And a humble hammer too, but not the false humility of the pietist.

"But the church finally decided — very deliberately — against Marcion and in favor of a diverse witness." (StampDawg)

Actually it decided in favor of no witness. I mean there were gospels like the gospel of Peter that were written as first person accounts, but they very deliberately rejected that in favor of contradictory presentations clearly written by latecomers and making no pretence to being first person accounts. The one who call 'Matthew' says "and Jesus passing by saw a man named Matthew…" showing clearly that although fundamentalists consider it a first person account, it isn't. Why was 'orthodoxy' against first person accounts? You could say the gospel of Peter was docetic, but so what? Its not like they didn't edit the clearly Marcionite gospel of John to make it more 'orthodox.' Why couldn't they ave done this with the gospel of Peter? They could have. But for some reason the 'orthodox' were diametrically opposed to gospels written as first person accounts.

And as for the notion that Marcion cut the gospels apart and reassembled them, it clearly goes the other way around (the proto-orthodox cut Marcion's gospel apart and iterpolated around the parts to produce four gospels). See Joseph Tyson's Marcion and Luke-Acts: A Defining Struggle. Marcion's gospel preceded both Luke and Acts.

Beowulf2k8- I'm not specifically familiar with Tyson's argument, but it's important to remember that we don't actually have any of the writings of Marcion, so it's unsure to what degree he wrote a new gospel, or snippets of the four canonical gospels. And while the Gospel of Peter (of the fragments we have) claims to be written by Peter, it's commonly held that it wasn't written until the second half of the 2nd century. It's docetic tendencies demonstrate this later dating. I'm also not sure where you get the idea that the Gospel of John was edited to make it less marcionite. I'm willing to allow for a Johannian redactionary process, but I have yet to see any marionite trends.

I'm also not sure what you mean by a rejection of eye witnessed accounts. To my knowledge, NONE of the gospels, canonical or otherwise, are first person accounts. Even if there was such an account, why would that account be more correct? One could argue that the historical distance allows for a greater degree of "objectivity."

How do you see the synoptic Gospels as being so different?