An interesting op-ed by Bruce Feiler recently appeared on CNN talking about the role of Moses in American politics. It seems that Moses as a deliverer in the Exodus and a lawgiver on Mount Sinai finds an integral significance in the history of America.

As Feiler notes,

By the time of the Revolution, Moses had become the go-to narrative of American freedom. In 1751, the Pennsylvania Assembly chose a quote from the Five Books of Moses for its State House bell, “Proclaim Liberty thro’ all the Land to all the Inhabitants Thereof — Levit. XXV 10.” The future Liberty Bell was hanging above the room where the Continental Congress passed the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. Congress’ last order of business that day was to form a committee of Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and John Adams to design a seal for the new United States. The committee submitted its recommendation that August: Moses, leading the Israelites across the Red Sea. In their eyes, Moses was America’s true Founding Father.

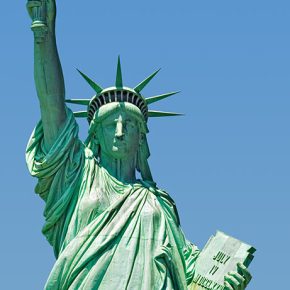

George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and Martin Luther King Jr. have all been compared to Moses in their role as a savior and lawgiver. Washington delivered America from the oppressive British and presided over the drafting of the Constitution. Lincoln ended slavery through military force and the Emancipation Proclamation. MLK spoke of leading African Americans into the Promised Land. Even the Statue of Liberty (of all things!) is modeled after Moses. The spikes on her head and the tablet in her arms mimic Moses’ iconic pose as he was walking down the mountain with a radiant face and carrying two tablets. In every instance the message is clear: Freedom depends on the law.

Yet every American reference to Moses ignores the fact that the law Moses brought did not bring life and freedom, but it instead brought condemnation and death. St. Paul says “Once I was alive apart from law; but when the commandment came, sin sprang to life and I died” (Romans 7:9) or “The letter kills” (1 Cor. 3:6). Moses (and the Law) did not bring the way of freedom, but rather he brings the way of death! In these passages, Paul refers to a concrete event in the history of Israel – the giving of the law at Sinai. This Pauline reading of the Old Testament understands that after the giving of the law nearly every Israelite that was delivered from the slavery of Egypt was killed by God in the wilderness (see Numbers 26:63-65!). The advent of the law is also the advent of God’s judgment upon his chosen people. Indeed, the giving of the law at Sinai is the dividing-line of the entire Torah between the salvation of the Exodus and the demise in the wilderness.

The law promises that it will bring order, peace and prosperity yet in actual fact it proved to be a ministry of death. As Francis Watson has suggested “the law that brings with it the conditional offer of life is overtaken by the realities of sin and death, so that those who are under law are under its curse” (277). With the conditional promise of life also comes the equal threat of death to the transgressor. For Israel and all who are under law this conditionality is only ever experienced as judgment and death.

The link between the law and freedom may be foundational to the American identity, whether conservative or liberal. But this link does not find its origin in either Moses or Christianity.

COMMENTS

11 responses to “Moses: Our Founding Father of Freedom?”

Leave a Reply

great post!

Moses himself died a failure, merely seeing but not entering the promised land, having disobeyed the Lord. Moses' life is a disturbing example of how even among the most famous faithful their lives can end having not accomplished what God set out for them to achieve. I have found that with fellow American Christians it is almost scandalous to suggest that God has in fact often appointed men and women to go tackle missions that are quite literally impossible. When they doubt me I point out that if Abraham was commanded to kill Isaac then God gave Abraham a task that God Himself thwarted. Paul understood the implication of these impossible missions saints int he past failed to achieve, the failures of people helped to highlight that the work was ultimately God's. We fail when we attempt to accomplish on behalf of God what God says is required but God is able to accomplish Himself for us what we are incapable of. Since I'm job hunting right now I have to keep this more in mind than if I weren't.

One of the primary purposes of "civil" law is not to give "freedom" but to constrain evil and the exercise of raw, arbitrary power by those who are sinners over those who are less powerful sinners. This is a very modest goal, and one that both the OT and Paul endorse as God-given. When this form of "law" (for example, the Civil Rights Act of 1964) is broadly in line with both Biblical morality and a Biblical skepticism about human nature, it can have beneficial, though limited, effects. For example, it can "free" the slaves, or it can "free" poor people from being thrown into debtors prison by those who, if not restrained by the law, would and have exercised oppressive control over their less powerful neighbors. This form of "law" cannot, of course, give ultimate "freedom", which is freedom from "the law of sin and death." Only Jesus did that. On the other hand, this does not mean that "law" or "government" is worthless or somehow necessarily our enemy. Washington is not Moses, but Ron Paul ain't Jesus, either 🙂

WTH- I think you're on to something there. Thank God we're not (ultimately) held accountable for our failure!

MC – I think you bring up a very valid point that I don't wholly disagree with. The distinctions between the uses of the law (and two kingdoms, etc.) are thoughtful attempts to safe guard Christian proclamation from worldly rule, and allow reason to create efficient governing.

The trouble with such distinctions is that they do not always square with biblical exegesis.

So far as the Torah is concerned, it does not make any distinctions between moral and civil law, instead there is a union of the two. Yes, the Torah proposes a theocracy and our historical situation has changed. But the Israelites were judged by God for their disobedience of the law in its entirety, not simply its moral commands.

NT-speaking, in the same way that "works of the law" is not exclusively a reference to ethic boundary markers, it is also not only a reference to moral law. "Works of the law" encompasses the entirety of the Moses legislation and its false promise of life to the one who does them.

More broadly, I think the founding fathers are reading Philo reading Moses, that is, they are reading Greek philosophy into their understanding of Moses and the law. For Philo, the law is the universal ordering of the cosmos, (instead of something in reference to God). Consequently, true freedom comes through the following of this law.

So while Luther emphasizes freedom FROM law, Calvin emphasizes freedom FOR law, there is no Christian way to speak of freedom THROUGH the law.

Todd– Although you might not "wholly disagree" with my comment, I can't imagine what in my comment you might NOT agree with. I do wish that you would cite a particular thing I say in the comment, and then tell me why you disagree, if you do. This "I don't wholly disagree" stuff sounds a lot like lawyer talk to me 😉

As for the Mosaic law, it was given along with the sacrificial temple worship. That fact should never be forgotten or minimized. In addition, an understanding of the Mosaic law as ONLY bringing death and, as you claim, a "false" promise of life, completely ignores the enormous good that Mosaic law did in the sense of ameliorating the harsh treatment of widows, orphans, slaves and others who were the "weak" of the time. Although Paul does say that "the Law" brings death, he says that this death that results is caused by our own sinful nature, not because of the nefarious nature of "the law" as such. This is where Paul and antinomianism part ways. In fact, Paul cites "the law" as one of the very positive gifts that come with "being a Jew." While the law given by God to Moses was, by God's own design, unable to produce the righteousness it demands, and instead results in death because of "the weakness of the flesh", this does not mean that we should see God's law as somehow our sworn enemy. That is no more Biblical that seeing "the law" as our savior.

So I'm the lawyer huh? I should have been more of a lawyer and offered a more nuanced explanation. You're right to suggest that the failure of the law's promise of life is due to inability.

And it's true that the mosaic law has provisions that can be called merciful. You identify several positive instances where the law protects the powerless. I would suggest that these provisions are generally what I would call the law's "promise of life." Failure to fulfill this law ends in divine judgment, according to the provisions of the law. So yes, the law does offer a choice of both life and death. Yet a narrative reading of the Pentateuch demonstrates that this offer, while a sincere possibility, did not actually produce life. The law is good, yes, but its conditionality led to the judgment of the nation.

Todd–We are in agreement. I just think that it is crucial when we talk about "the condemnation of the law", that we are talking about being "justly condemned" by God's good law. Otherwise, we end up with a petulant brat "I don't want to be told what to do", "victim" gospel that is light years away from anything Paul or Luther taught.

Michael– Yes, justly condemned. The fault is not with the law, it is always "good"- even if this goodness means our death!

Michael (great t have you back!),

There is a lot that could be said about your position, because there is a connection between the power of the Law and God's wrath which, almost, equates the two. Therefore, no matter what positive intent the law had, its universal result was the execution of God's wrath on humanity. As the Apostle says, "the very thing that promised life, proved death."

When we talk about that "death," as when we talk about the distinction between the "uses" of the law, I think we run the risk of getting lost in abstractions. The gateway to an awareness of being "justly condemned," is usually in the experience of being, among other things, a "petulant brat." People may never (and who really does) connect with the former, but the latter (or something like it) is usually where people begin.

some thoughts!

This is not to say that the Law is not "good" in some sense, in the same way that God is Holy, but what does that mean when it was never experienced as such?

Is the "goodness of the law," like the Hindu who argues that everything we experience as reality is an illusion, which then begs the question, why is everyone so deluded?

Clearly, we have to work with the assertion that the Law is Good–but I'm more inclined to read that through the equally biblical and equally Pauline position that the "law is spiritual." . . . In this case, the Law as semper accusat takes the form of whatever crushes, condemns and kills. There is no practical/phenomenological difference between the "just condemnation" of God and the condemnation of a boss, father, friend, etc. . . Our job, I would suspect, is to connect the two.

But, IMHO, the longer we deal in abstractions like "just condemnation," the longer people are left disconnected from what truly ails them which is, ironically, the "just condemnation" of a Holy God. . . When we have a static view of the Law as Good(just a static view, not that this view is wrong) then the only way to have a proper view of the law is to see just how little we match up to it. This leaves many Preachers the sole task of connecting how "good the Law (ie God in this scheme) is and how bad we are." Consequently, "spirituality" becomes a game of "one-downmanship," where the most spiritual is the one who has the greatest conception of how Holy God is and how unholy he/she is. There has to be another way, because ask the now Unitarians how well the legacy of Jonathan Edwards and his "Sinners in the hands of an angry God" is holding up.

Again, I'm not disagreeing with the underlying theological truths of any of this, but there are ways of going about it that seem to connect to where people actually live rather than the places that they need to inhabit in order for our schemes to make sense. (and, sadly, I stand fully condemned by that last statement as well)

anyway, clearly nothing fully worked out here!

some more Good Friday thoughts!

Jady–I understand the aversion to repeating abstractions. However, as for the idea of "just condemnation" or the "holiness" of God , there is nothing inherently more abstract about these ideas than there is about "law/gospel". One can preach a very boring, abstract "law/gospel" sermon just as poorly as one can go on and on about "holiness".

What I am trying to distinguish, and I think it is an important distinction, is what it really means to be "condemned" by God's law. Now I am sure that the Aztecs felt "condemned" when they couldn't round up 20,000 folks to slaughter in any given month, but I don't think that it would help explain the gospel to them to tell them that Jesus died so that they could feel better about not being able to live up to their human sacrific quotas. I might be able to really "connect" with "where they are at" in terms of their "feelings" of being "crushed" but I doubt that I am connecting them with the gospel.