Back in July, many of us at Mockingbird discovered (see earlier blog posts here and here) the writings of Mark Galli, Senior Managing Editor of Christianity Today, the flagship magazine of Evangelicalism (started in 1956 by Billy Graham). Galli’s grasp of the Gospel—God’s grace in Jesus Christ to broken human beings (including Christians who can’t get it together)—was as deeply refreshing as it was (almost) unique in the wider world of Evangelical Christianity. We were so intrigued that we sat down with him to find out more. It proved to be a fascinating conversation about the current landscape of Evangelicalism, the radical nature of the Gospel, and the pattern of the Christian life. UPDATE: Mark Galli will be the keynote speaker at the 2011 Mockingbird Conference in New York City, 3/31-4/2. Go here for more information.

Back in July, many of us at Mockingbird discovered (see earlier blog posts here and here) the writings of Mark Galli, Senior Managing Editor of Christianity Today, the flagship magazine of Evangelicalism (started in 1956 by Billy Graham). Galli’s grasp of the Gospel—God’s grace in Jesus Christ to broken human beings (including Christians who can’t get it together)—was as deeply refreshing as it was (almost) unique in the wider world of Evangelical Christianity. We were so intrigued that we sat down with him to find out more. It proved to be a fascinating conversation about the current landscape of Evangelicalism, the radical nature of the Gospel, and the pattern of the Christian life. UPDATE: Mark Galli will be the keynote speaker at the 2011 Mockingbird Conference in New York City, 3/31-4/2. Go here for more information.

Here’s Part 1 of the interview.

Mockingbird: Christianity Today is a magazine written for a broad spectrum of theological perspectives. But in your regular Soulwork column, you have a distinct theological perspective that emphasizes God’s radical grace in the face of our human brokenness and narcissism. What’s the origin of your perspective and what role does it play in the magazine?

Mark Galli: You’re right that Christianity Today is a magazine for all evangelicals. So my job involves publishing stuff I may disagree with on a personal theological level. But CT is like a village green. People from all backgrounds can come together and talk about what they think they should be doing in the name of Christ in the world. In that, there’s a certain continuity and coherence, maybe less than there used to be, but it’s still there: a passion to love Christ and serve him in the world.

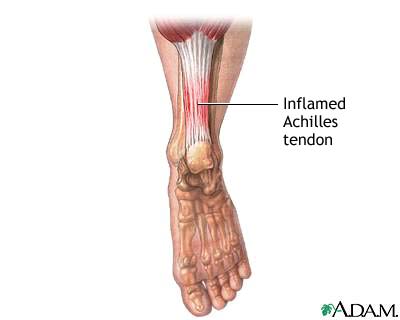

This kind of activism has characterized evangelicalism from day one. That, to me, is our movement’s greatest strength and our Achilles heel. That is, on the one hand, I’m just always impressed how when you go to the far reaches of the planet and you find people who are working in the worst situations, they’re evangelicals. But at the same time, that activism is almost like an addiction. We need a voice in there saying, “Now, let’s remember from whence all this activism comes; what is its root and where is it leading?”

This kind of activism has characterized evangelicalism from day one. That, to me, is our movement’s greatest strength and our Achilles heel. That is, on the one hand, I’m just always impressed how when you go to the far reaches of the planet and you find people who are working in the worst situations, they’re evangelicals. But at the same time, that activism is almost like an addiction. We need a voice in there saying, “Now, let’s remember from whence all this activism comes; what is its root and where is it leading?”

So one of my concerns as a writer and as the Senior Managing Editor of CT is to keep ringing that bell, that it all begins with God. And it all ends in God. And that it’s all done through God and through his grace. Anything that we achieve or call an achievement—even using that word “achievement” is problematic—has to be understood as God’s achievement. So in fact, the cover story, which I wrote, for the October issue was called, “In the Beginning, Grace.” And it’s an overview of what I consider to be the main concern with the evangelical movement right now; it’s addicted to the horizontal: what we do, what we’re doing wrong and how we should fix it. And I make a case that the very first thing we should do when we see a horizontal problem in the movement is that we should think vertically. We should be looking to the cross, first and foremost. So that is kind of a public setting of a statement that I hope we will be emphasizing in the magazine. And again, not at the expense of all the great things evangelicals are doing, but to keep pounding home the priority of grace in everything we do.

There was a lot of heated response to your recent column, “The Scandal of the Public Evangelical.” You said that being sanctified in this life is mostly about becoming increasingly aware of just how much we are, as the Book of Common Prayer says, “miserable offenders” and there “is no health in us.” Essentially, realizing how bad we are, and the immensity of God’s grace, and simply relying on that. Some people loved it, some hated it. One guy called it “appalling grace.” Why are people so heated in their response to this?

I don’t know that I’ve talked about grace in the radical nature in which Paul and the New Testament talk about it unless people are shocked and appalled by what I’ve said. The doctrine of grace is so radical and so contrary to our assumptions about what religion is about, that once we express it in a clear fashion, it will appall people. Because we’re all so anxious—even people like me who preach grace—to justify our lives. We want our lives to be meaningful, purposeful, useful. So we hook our futures to God and think, “Now I can really make my life purposeful and useful and I can do something for God in the world. And if I work with God, he’s going to change me.” We’re not so interested in God a lot of times, we’re tired of who we are and we’re more interested in wanting to be a different kind of person so we can feel better about ourselves. So much of our religious language and religious motive is about ourselves: justifying ourselves or improving ourselves, with God as a means to that end. Well, the fact of the matter is it’s not about you. But that’s shocking and appalling to most people because we’re so used to thinking that religion is about us, even though we’ve learned to use religious language to suggest otherwise. But in fact, it really ends up being all about us.

The other thing is the whole business of “transformation.” I notice how often that word comes up—our lives can be transformed, our churches can be transformed, our culture can be transformed. We imagine if we do everything right according to what the New Testament teaches us, that things will be completely changed. And if they aren’t completely changed, I’ve either bet my life on something that’s not true, or the Gospel itself is not true.

I just keep on coming back to Luther’s truth that we are simultaneously justified and sinners. I keep on looking at my own life, and at church history, and I realize that when the Gospel talks about transformation, it can’t possibly mean an actual, literal change in this life of a dramatic nature, except in a few instances. It must be primarily eschatological; it must be referring to the fact that we will in fact be changed. The essential thing to make change possible has occurred—Christ died and rose again. (And in this life we will see flashes of that, just like in Jesus’ ministry there were moments when the Kingdom broke in and we see a miracle. And these moments tell us there is something better awaiting for us and God is gracious enough at times to allow a person or a church or a community to experience transformation at some level.) But we can’t get into the habit of thinking that this dramatic change is normal, this side of the Kingdom. What’s normal this side of the Kingdom is falling into sin (in big or small ways), and then appropriating the grace of God and looking forward to the transformation to come.

Now, some people would say that it’s depressing that I can’t change. Well, it’s not depressing, it’s freeing! It’s depressing and oppressive to think every morning that I somehow have to be better than I was the day before to justify my Christian religion and to justify my faith. That’s the oppressive thing. The freeing thing is to realize that I am a sinner and God has accepted me as such. And yes, of course we’re called to strive and be better and to love and all those things—duh!—that’s not the issue. The issue is the motive out of which that comes and what we actually expect to happen as a result of that.

say that it’s depressing that I can’t change. Well, it’s not depressing, it’s freeing! It’s depressing and oppressive to think every morning that I somehow have to be better than I was the day before to justify my Christian religion and to justify my faith. That’s the oppressive thing. The freeing thing is to realize that I am a sinner and God has accepted me as such. And yes, of course we’re called to strive and be better and to love and all those things—duh!—that’s not the issue. The issue is the motive out of which that comes and what we actually expect to happen as a result of that.

A lot of this is driven by my own personal spiritual journey and is hammered home by the biblical message, and something that Luther got really well: the harder I try to be a good Christian, I notice the worse Christian I am: more self-righteous, more impatient, more frustrated. But when I stop trying to be a good Christian and just realize I am a sinner and that God has accepted me, and that’s the way it is, that, for some reason, releases the striving part of me that makes life harder, and all of a sudden I find myself, surprisingly, more patient, more compassionate, less judgmental and more joyful. So I think that kind of personal experience is a merely reflection of what the Gospel truth is. And those moments when I experience that, that’s wonderful.

Many people have a personal story of going from legalistic Christianity to a new Gospel-focused faith centered on the cross, often due to some personal crisis. You talk in your book Jesus Mean and Wild about suffering being that thing which “plows the field” of the human heart so that grace can come in. Was that you?

Well, that for me is what sanctification is all about. It’s the see-saw, the going back-and-forth. The natural human nature wants to take over and begin building that tower that reaches to the heavens. That is part of the original sin of wanting to know the difference between good and evil, so we’re going to pluck that fruit from the tree. We just want to do it all the time; I want to do it all the time. There have been many moments, many times in my life when I’ve had to stop and say, “You know, this isn’t working. And the reason it’s not working is that I’m trying to build this tower up to the heavens.” And I think that’s the nature of the Christian life, building the tower and then have it come crashing down, and then having the reality of the Gospel sink deeper and deeper into your life. It’s something as a preacher and a speaker you have to face into.

When I was a prea cher, one of the ways I had to learn it was every single week I had to stand up and say something to the congregation. And there were some weeks when I could stand up there and say, “I’m doing okay in this regard.” But most weeks, “I don’t know why I’m standing up here saying this. I don’t know that I have my act together.” What occurred to me was that it wasn’t about me as a preacher having my act together before I can proclaim the grace and mercy of God. It’s about something bigger than myself. And that thing that a preacher is forced to confront every Sunday morning, if he has any sense of self-awareness, is the same thing that all of us have to confront when we step out of bed: “Whose day is this? Is this my day to show God how much I can achieve for him? Or is this my day to live in his grace and see what comes of it?”

cher, one of the ways I had to learn it was every single week I had to stand up and say something to the congregation. And there were some weeks when I could stand up there and say, “I’m doing okay in this regard.” But most weeks, “I don’t know why I’m standing up here saying this. I don’t know that I have my act together.” What occurred to me was that it wasn’t about me as a preacher having my act together before I can proclaim the grace and mercy of God. It’s about something bigger than myself. And that thing that a preacher is forced to confront every Sunday morning, if he has any sense of self-awareness, is the same thing that all of us have to confront when we step out of bed: “Whose day is this? Is this my day to show God how much I can achieve for him? Or is this my day to live in his grace and see what comes of it?”

Who have been your theological allies and mentors along this path? Who has influenced you? You’ve talked about Luther, you’ve mentioned Barth. Who else would you put on that list?

Probably those two would be the most important. Though who I’ve read the most is Karl Barth. Especially recently. That’s probably why you’re seeing a new intensity in my writing on this. I’m exploring writing a book on Barth. And in the course of doing that I was reminded how much I really like this guy. I had not read him in twenty years, but whenever I do read him, he absolutely thrills me with the radical nature of God’s grace to us. What I’m really trying to do is to understand in Barthian terms, how that moment of God’s alienation, when we feel alienated by God, when we feel judged by God, that God is the stranger, that God disapproves of us, that at that very moment it’s the God of mercy who’s beginning to work in our lives. And that’s what I’d like to bring out in a book.

Bonhoeffer in my 20s was really important. I’ve also read a lot of Orthodox spirituality. There are two types – there’s the “climb the spiritual ladder” type, which always feels dreary to me. And there’s another type of Orthodox theology which is radically God-initiated and grace-centered. And that’s what I’ve always appreciated.  But in reality, I don’t often know who my influences have been. One of the weaknesses of my writing, is I can write long, long passages and never actually quote anyone. And I don’t quote anyone because I don’t consciously know where I’ve gotten this information. And I pridefully think, “Wow, this is good, this is fresh.” And then I’ll pick a book that’s gotten dusty on my shelves, that I’ve marked up 20 years ago and I’ll realize it’s all from that author. The older I am, I realize I don’t have an original idea in me.

But in reality, I don’t often know who my influences have been. One of the weaknesses of my writing, is I can write long, long passages and never actually quote anyone. And I don’t quote anyone because I don’t consciously know where I’ve gotten this information. And I pridefully think, “Wow, this is good, this is fresh.” And then I’ll pick a book that’s gotten dusty on my shelves, that I’ve marked up 20 years ago and I’ll realize it’s all from that author. The older I am, I realize I don’t have an original idea in me.

CLICK HERE FOR PART TWO.

COMMENTS

14 responses to “Exclusive Interview: Mark Galli of Christianity Today (pt. 1)”

Leave a Reply

Stellar stuff! I can't wait for the rest.

absolutely wonderful!

Thank you!

This line especially preached to me personally:

"We’re not so interested in God a lot of times, we’re tired of who we are and we're more interested in wanting to be a different kind of person so we can feel better about ourselves."

Thanks so much.

Great interview! I can't wait for pt. 2 when he talks about his love of Mockingbird and vampire movies.

Thank God for this interview. It is a much needed reminder that I'm not alone and not crazy.

You are not alone and you are not… um…

crazy.

I get a sick, queasy feeling when I hear the following phrases:

"It's not about you, it's about God."

"Whoever loses his life will find it"

timuth

'I get a sick queasy feeling'

me too! I want it to be ALL about me. truth. Only Jesus could deliver me from this dis-ease.

Refreshing to hear that though he qualifies his statement, Galli hasn't interpreted a theology of grace as entirely incompatible with the works of Barth and some Orthodox writers. I wasn't expecting that, but a valuable and helpful point, nonetheless.

Aaron,

Fantastic interview! Thank you

Can't want for part two of this interview. I'd read Galli's little book on St. Francis and you see here are there in the book that he notes Francis' inconsistencies (his ladder climbing), in the midst of his receptivity to God. I don't think I've ever read anyone who criticized St. Francis, drawing out the distinction between a striving that tries to make ourselves feel better about ourselves, and a striving that humbly recognizes that whatever "gains" we make, it is all God's work.

Wonderful, comforting, lifting, needful, honest, and just plain unvarnished Gospel. When you have lived with a "gospel" of trying to be, do, overcome, be significant, rise above etc etc etc and didn't…one either turns away in despair because he didn't "get it right" or finally sees that God loves sinners. Grace is unhuman. I love the interview.