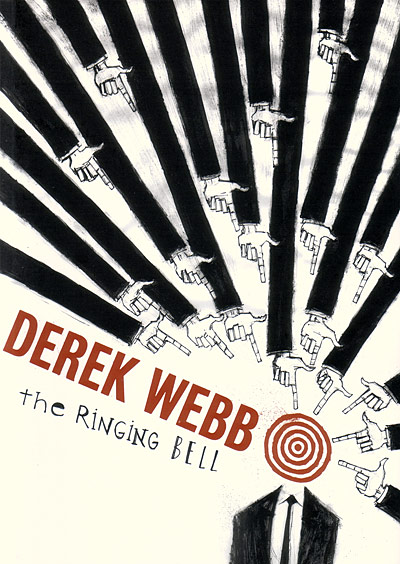

It’s no secret that musician Derek Webb has long been an inspiration, and not just because of his 2005 album Mockingbird. Like any artist worth paying attention to, his path has taken a number of dramatic twists and turns, most recently with the release of the controversial and predominantly electronic Stockholm Syndrome. Last week I had the great privilege of speaking with Derek about a number of things, among them the new record, the unpredictable trajectory of his career, the concept of “Christian” artistry and the mad genius of rapper MF Doom. Regardless of what one makes of the issues he addresses on Stockholm Syndrome, after hearing his thoughts on the process, I found that my admiration and respect for the man (and the record) only increased.

It’s no secret that musician Derek Webb has long been an inspiration, and not just because of his 2005 album Mockingbird. Like any artist worth paying attention to, his path has taken a number of dramatic twists and turns, most recently with the release of the controversial and predominantly electronic Stockholm Syndrome. Last week I had the great privilege of speaking with Derek about a number of things, among them the new record, the unpredictable trajectory of his career, the concept of “Christian” artistry and the mad genius of rapper MF Doom. Regardless of what one makes of the issues he addresses on Stockholm Syndrome, after hearing his thoughts on the process, I found that my admiration and respect for the man (and the record) only increased.

Sidenote: We reviewed Stockholm Syndrome a few weeks ago, and after speaking with Derek, I wanted to make two amendments: 1. I was completely wrong about the subject matter of “Jena and Jimmy” and 2. There is nothing sweet about “I Love/Hate You” – it is absolutely consistent with the rather brilliant theme of the record – that we fall in love with things that destroy us.

Real quick and first off: Not sure if you know, but part of the inspiration for our name came from your record and song Mockingbird.

Man, that’s amazing, and I did hear that. It’s an honor. I’m so glad that resonated with you guys.

That album was a breath of fresh air, right when a lot of us needed it. I love all your records, but I love that one the most.

Musically is a pretty easy thing to explain. I’ve always been fairly restless artistically; I try not to stay in one spot very long. But the one thread that I have always tried to follow is the thread of folk music. Folk music as an approach, not really as a style – music for folks, the unfiltered stories of the people, the telling of what’s happening in the culture. I initially connected with it when I got into the protest music of the 60s and 70s.  Guthrie and Dylan and Pete Seeger and Joan Baez, they were really putting their art on the concerns and stories of the people and what was happening in that time and place. Their music seemed to transcend itself and connect people to a bigger narrative; it had an implied importance to it, and I was always really drawn to that urgency. A lot of that was more acoustic music. But here in more recent decades, acoustic music hasn’t really carried that thread so much.

Guthrie and Dylan and Pete Seeger and Joan Baez, they were really putting their art on the concerns and stories of the people and what was happening in that time and place. Their music seemed to transcend itself and connect people to a bigger narrative; it had an implied importance to it, and I was always really drawn to that urgency. A lot of that was more acoustic music. But here in more recent decades, acoustic music hasn’t really carried that thread so much.

When I tried to trace that approach, I actually picked it up in a lot of urban music, a lot of hip-hop. That seemed to be the contemporary folk music, where you can hear the unfiltered stories of the people, talking about culture, what’s really going on, etc. Once I investigated how that music was made, I started to get excited about the limitless possibilities of more inorganic music. Because in a lot of the pop/rock stuff that I typically had recorded, you’re limited to the instruments physically represented in the room. With computer generated and electronic, synthesized sampled music, any sound that you can hear in your head or anywhere else you can essentially incorporate into the music. Suddenly all of these sounds and all of this energy are at your disposal. That’s what initially got me interested in trying my hand at it.

I love the One Zero Remix album and I think your music lends itself well to that sort of production. I remember in the Wilco documentary where Jay Bennett says something about how if you’re not careful, songs written/played on acoustic guitar can easily end up sounding like “folk ditties” – in the pejorative sense – that you need to dress them up somehow to make them more exciting.

Yeah, exactly. I’ve tried the front-door approach to that over the years. I’ve played guitar for more than 25 years, so that’s my go-to instrument, the one I know the best. So I’ve done a lot of writing on guitar, and on some of the records over the last few years, try to deconstruct the song to the point that it’s more interesting than just some dude on acoustic guitar. This time around, with one or two exceptions I didn’t write any of these songs on acoustic guitars. My primary concern was that the music was evocative, that the feeling was right, that the soundscape evoked the right things, that before you heard lyric or melody, it made you want to move.

[My collaborator] Josh Moore and I spent several months just allowing some of those sounds and beats and loops to simmer a little bit. Let the whole thing stew to the point where the sound of the record was what we wanted. Where it had an immediacy and an urgency, so that you would hear it and immediately connect with it. At that point the album was 60% recorded, and it wasn’t until then that I actually started writing the songs. Which was a completely backwards process for me. I typically don’t go near a studio until I’ve considered and over-considered every conjunction in every song. But this time around, I wrote the lyrics and the melodies to the record that we had already made, which was essentially instrumental. So the whole process was so different and actually completely opened a whole new realm of creative possibilities for me.

I watched the documentary [“Paradise Is A Parking Lot”] you guys put out. You’re clearly talking about a lot of serious stuff, but it looks very much like you and Josh were having a blast. And then with the LOST-inspired scavenger hunt leading up to the release, you seemed to be firing creatively on all cylinders.

Absolutely. I feel like this whole project has been a deeper expression of my full personality than anything I’ve done prior. This was the most enjoyable process of all the records I’ve made by far. It’s that immediacy.

Being able to reconnect with Josh and do something that both of us are good at – he’s such a gifted programmer and producer – and to be able to do it just the two of us (so fewer cooks in the kitchen), I loved every moment of it. When we ran into trouble with the label, we at first tried to guard the creative space and not let it impede the process in any way. But then we decided to try and make something engaging out of the trouble. That then fed into the energy of the record. I don’t expect to be able to recreate anything like this again. It was so synergistic and special. But I feel like every project has that element to it for me. I shoot from the hip, I don’t make a lot of plans, I’m not masterminding anything about my career. I never know what’s around the next corner. I’m always surprised about where I end up. Just this time it was more so.

Being able to reconnect with Josh and do something that both of us are good at – he’s such a gifted programmer and producer – and to be able to do it just the two of us (so fewer cooks in the kitchen), I loved every moment of it. When we ran into trouble with the label, we at first tried to guard the creative space and not let it impede the process in any way. But then we decided to try and make something engaging out of the trouble. That then fed into the energy of the record. I don’t expect to be able to recreate anything like this again. It was so synergistic and special. But I feel like every project has that element to it for me. I shoot from the hip, I don’t make a lot of plans, I’m not masterminding anything about my career. I never know what’s around the next corner. I’m always surprised about where I end up. Just this time it was more so.

Most of the people that I know who love your music find your restlessness so appealing. I wonder, being so inspired by protest music and folk music, if people try to make you their spokesperson. Has that been a struggle for you?

A little bit. I’ve tried to avoid that as best I can. My career has been an intentional cycle of self-sabotage in order to keep anyone from liking me too much. I think it’s healthy to turn a third or half of your fanbase over every five years or so. I lose or gain some every time around. I think the fact that I am pretty restless stylistically and the fact that I tend to take pretty seriously both my role and the position that I’m in – for whatever reason – to be able to speak in a pretty unfiltered way. Not a lot of artists have that liberty. That all has worked pretty well into my goal of self-sabotage.

But I imagine people want to label you, and being on a label devoted to Christian music, I’ve heard you talk refreshingly about those not really being categories that you’re interested in. Coming up against that in the process this time – it sounds like it was inspiring to you. Is that fair to say?

Initially it was really disheartening. I’ve never in my solo career felt like what you might call a Christian artist. I don’t even know what that could possibly mean. I’ve given up trying to find clever definitions for those terms. I’m a guy like any other. As an artist, my job is to look at the world and tell you what I see. Every artist, regardless of their beliefs, has some way that they look at the world that helps them make sense of what they see. A grid through which they look at the world which makes order out of it. For me that’s following Jesus, for other artists it’s other things. It could be anything, but every artist has that grid. Most Christian art unfortunately is more focused on making art/writing songs about the grid itself. I’m more interested in looking through the grid and telling you what I see.

Now I don’t forbid myself from writing about the grid, I’ve done that from time to time. But as a whole, not a huge percentage of my life is spent in the throes of doctrine and theology. That stuff is the framework of all of my dialogue, but I’m just not interested in talking about it all the time. So I’d rather live life and talk about it than talk about living life. I think we have enough people talking about spirituality. I would rather engage with my spirituality and tell you what the result is. Because art is at its best when it’s not being used as a tool. That’s an awkward use of art – as a Trojan horse to communicate an idea or to push your worldview. You certainly can, you’re at liberty to do that…

Now I don’t forbid myself from writing about the grid, I’ve done that from time to time. But as a whole, not a huge percentage of my life is spent in the throes of doctrine and theology. That stuff is the framework of all of my dialogue, but I’m just not interested in talking about it all the time. So I’d rather live life and talk about it than talk about living life. I think we have enough people talking about spirituality. I would rather engage with my spirituality and tell you what the result is. Because art is at its best when it’s not being used as a tool. That’s an awkward use of art – as a Trojan horse to communicate an idea or to push your worldview. You certainly can, you’re at liberty to do that…

But it can be patronizing.

Yeah, it kind of robs the art of all of what’s great about it. I want people to be able to listen to my records regardless of their beliefs and find some way in, something to connect to, something abstract. The more I talk about the categories, the more it alienates people before they have even had a chance to get their ears on it.

That’s profound. I’ve heard you say that this is your most personal record. Tell me what that means.

If I said it as broadly and simply as I could, Stockholm Syndrome is the sound of me using the resources at my disposal as a barricade between people whom I love and people in my own community – the church – who are spewing hatred and judgment all over those people whom I love. This is me basically trying to absorb some of that judgment and hatred that my friends can’t help but receive because of how poorly my community deals with their particular lifestyle. That’s essentially what this record is. You’re hearing the sound of it.

But it doesn’t seem to be a one-issue record.

It’s not. But there’s so much of that there. A lot of people make the mistake of thinking of me as guy who has some kind of a plan, some kind of a point that I’m trying to make, or something I’m desperately trying to communicate, some agenda that I’m trying to push. And that just couldn’t be further from the truth. I can’t tell you how little intention I have going into records – again, I’m looking at the world and telling you what I see. But I’m a conceptual thinker, so it does tend to connect when it’s over, it does seem to have themes. I made this record for my friends. I don’t have any kind of goals with it. People ask me whether the language or style might alienate people from hearing the message I’m trying to convey. And my answer is, I have no idea what you’re talking about. Because I don’t have any kind of message I’m trying to convey. I’m just a guy telling you what I see. Behavioral change or people changing their views on issues, that’s not the business I’m in. Once the record is made and it goes out there, I just hope people hear it and that some people resonate it.

That’s very courageous. Your art is what it is. It’s not a means to an end. It’s just Derek being Derek.

I’m just trying to do my job, that’s all I’m trying to do.

What’s the reaction been like? How are you dealing with it?

Kind of hard to tell. I’ve not been surprised by any of it yet. If you understand me, then you’ll understand the record. And if you’re not really interested in me, you might not like it. But I don’t think there’s some highbrow thing, where you have to be cool enough or, I don’t know, liberal enough to “get this”. And if you don’t “get it”, then that’s some sort of personality flaw on your part. I don’t think that’s true at all. It’s just like it ever was: either people resonate ultimately with me and therefore understand the art that I make. Or they don’t. Again, I don’t make music with the intention that very many people are going to like it. I don’t make music for mass consumption or appreciation. I never have. I don’t care if anyone likes the music I make, and I think that’s what makes me trustworthy to the few people who do like it. It doesn’t bother me.

Kind of hard to tell. I’ve not been surprised by any of it yet. If you understand me, then you’ll understand the record. And if you’re not really interested in me, you might not like it. But I don’t think there’s some highbrow thing, where you have to be cool enough or, I don’t know, liberal enough to “get this”. And if you don’t “get it”, then that’s some sort of personality flaw on your part. I don’t think that’s true at all. It’s just like it ever was: either people resonate ultimately with me and therefore understand the art that I make. Or they don’t. Again, I don’t make music with the intention that very many people are going to like it. I don’t make music for mass consumption or appreciation. I never have. I don’t care if anyone likes the music I make, and I think that’s what makes me trustworthy to the few people who do like it. It doesn’t bother me.

What I have seen is that it does seem to be pretty polarizing. People either really love it or really hate it. And I think that’s pretty great. I think it’s better when it’s more polarizing cause people waste less time. They hear it, they love it, they hate it, they move on or move in.

Well, speaking as an extremely cool person, I’m super glad it’s out on vinyl. That must be a thrill.

Yeah! I’ve never had one of my records hit vinyl before, so that’s been incredible and inspiring. I actually went to the plant here in Nashville the day that they pressed it. It was an incredible experience.

I would love to hear about what you’re reading and listening to.

I just got the new Wilco record – I’m such a fan of theirs – and I feel immediately like it’s going to be one of my favorites. Now that’s a band you can trust. It does not sound in any way like they care about what I think about their music. They are 100% trusting their instincts and doing what they think is good. And that’s why I feel I can trust them and that’s why I love their music. Their approach stretches me as a listener as opposed to my opinions as a listener stretching them to do something which isn’t really them.

I’m kind of obsessed with [rap-artist/producer/savant] MF Doom. Big time. He has several aliases under which he produces and records and writes, so I’m on a scavenger hunt to find it all. The record that hooked me onto him was the one he did with Danger Mouse (who I’m also totally obsessed with), Danger-Doom.

I’m kind of obsessed with [rap-artist/producer/savant] MF Doom. Big time. He has several aliases under which he produces and records and writes, so I’m on a scavenger hunt to find it all. The record that hooked me onto him was the one he did with Danger Mouse (who I’m also totally obsessed with), Danger-Doom.

Anything you’re reading? I hear Letter From A Birmingham Jail [by Martin Luther King, Jr] was a big inspiration on Stockholm Syndrome.

Yeah, yeah, I plagiarized those letters quite a bit on the this record. There’s more than handful of songs with words taken directly from those letters. I’d say that that’s some of the best writing on those issues. To be honest, though, I used to read a lot of non-fiction, but I rarely read it anymore. I almost always read fiction now.

What fiction?

I recently read Flashforward, a novel that came out years ago, sort of a tech-thriller. Just this great story, which I hear ABC is making a series out of, which I find hard to believe. I also loved Lucky Wander Boy by D.B. Weiss, which is about this guy who’s obsessed with video games – it’s sort of half a fictional story and half a history of video games. I’m also re-reading Harry Potter book 7 right now. I’m always re-reading a Harry Potter. And obviously Chris Anderson’s new non-fiction book Free. He’s a genius.

One last question: we’re dying to see how you adapt this stuff live. Is there any chance you’ll be making it to New York or the Northeast?

I’d say there’s a pretty good likelihood. The majority of the shows I’ll play in 2010 will be representations of this record. I’m not going to tour it with acoustic guitar. I’m going to have a three-piece out with me, a live drummer and at least one person on a laptop. That’s how we’re doing the release tour which starts up soon. My hope is that anywhere I’ll go I’ll have a band with me. And we’re certainly due for a show or two in that part of the world.

COMMENTS

4 responses to “Blind Bound By Love – An Interview with Derek Webb”

Leave a Reply

So what's Jena and Jimmy about? Tell us! Please!

Chris-

From the press release they sent me, written by derek:

“Justice in the System” sets the stage for “Jena & Jimmy,” my attempt to reframe the historical struggle between the civil rights movement and the U.S. government – particularly between Martin Luther King, Jr. and J. Edgar Hoover – in a contemporary, relational setting. In the broadest sense, I wanted to write about the struggle between those in power and those who are brave enough to withstand intimidation and have their voices heard.

so glad the two 'birds' could overlap

any chance of the whole press statement being published?